With a new outdoor sculpture unveiled at Kistefos Museum near Oslo and jewellery pieces in the collection of the V&A in London, Tone Vigeland has forged a unique place in Norway’s cultural history. Christian House surveys a single-minded vision spanning six decades.

This summer an octogenarian Norwegian jewellery designer accessorised a river valley an hour north of Oslo. When Tone Vigeland’s Sculpture 1, 2022 was unveiled at Kistefos Museum, the sculpture park founded by Christen Sveaas, it was in the presence of many of the nation’s leading curators, artists and patrons. The sculpture – a giant curlicue of steel and bronze that winds back on itself – emphasises Vigeland’s talent for finessed minimalism. “I am always striving towards simplicity,” she once remarked. “And this wish may take different shapes.”

Skulptur 1, 2022 by Tone Vigeland, recently unveiled at Kistefos (Photo: Vegard Kleven)

The Kistefos commission is the latest achievement in a remarkable career that has taken Vigeland from the rarefied world of cult jewellery in the 1960s, with pieces admired by collectors and worn by celebrities such as Marianne Faithfull, to the very public realm of monumental sculpture. As art historian Karin Hellandsjø notes, these two spheres intersect in her latest, site specific, work: “Abstract in idiom, Sculpture 1, 2022, almost seems like a distorted piece of jewellery as it changes expression every time you move around it.”

Portrait of Tone Vigeland, 2017 (Photo: Morten Andenæs)

Vigeland came to prominence as a studio jeweller in the early 1960s – she rejected the opportunity for making mass-production pieces – honing a distinctive union of form, with repetitions of organic and geometric motifs, and the monochromatic palette of silver and other materials. For inspiration, she looked to medieval chain-mail and traditional Viking crafts.

The result might almost be described as anti-jewellery. Like armour and tribal headdresses, its impact is forceful, even confrontational. Like aspects of nature, they are resolutely present on the person. And, as with the sharpness and strangeness of the natural world, they inspire a kind of nervous tactility: they attract like the spiky surface of a pinecone or the rhythms on a rockface.

Although removed from the whims of fashion, in the late 1970s Vigeland’s pieces were linked, by some, to the Punk movement. However, material and line dictate her design ethic, rather than the pursuit of trends. Discussing her ‘feather’ series – featuring metallic sprays and quills – she emphasised its accidental origins: “A friend from Bergen came to me with a set of black iron nails. I found that when I hammered them flat, they had a lovely character – almost like black feathers. First, I discovered the material, and then I found a design to suit it.”

“A nail, steel wire from a fence, bits of metal. In her hands, these are translated into a simple, beautiful and wearable form”

Cecilie Malm Brundtland, on Tone Vigeland

Vigeland “picks up on the artistic potential in what others would regard as junk,” says Cecilie Malm Brundtland, author of Tone Vigeland: Jewellery + Sculpture, Movements in Silver (Arnoldsche, 2004). “A nail, steel wire from a fence, bits of metal. In her hands, these are translated into a simple, beautiful and wearable form. Her dedication to creating wearable jewellery using the body to sculpt them is remarkable. Thanks to the way they are made, constructed out of a single element, endlessly repeated, her pieces follow every curve and line of the body and seems nearly inseparable from the people who wear them.” Now, Vigeland is creating a similar bond in the landscape.

Tone Vigeland, Neckpiece, 1983

Steel, silver, nickel-plated bronze mesh. Private collection (Photo: Hans-Jørgen Abel)

Tone Vigeland was born in Oslo in 1938 into one of Norway’s great artistic dynasties. Her great-uncle was the celebrated figurative sculptor Gustav Vigeland, who created a famous installation of works in Oslo’s Frogner Park. Tone’s paternal grandfather, and Gustav’s great rival, was Emanuel Vigeland, whose church decorations combined paintings, stained glass and frescoes. Her father was also a successful church artist. Tone grew up in a bubble of bohemian life.

Tone Vigeland, Bracelet, 1 of 3, 1984. Silver. The Museum of Modern Art, New York (Photo: Hans-Jørgen Abel)

Following studies at the Norwegian National College of Art, Craft and Design in the late-1950s, and a subsequent goldsmithing course, she worked for several years at the artists collective PLUS in Fredrikstad before striking out on her own in 1963. On visits to London, Vigeland would wander around the British Museum – “you could get lost in dim corners and feast your eyes on arrowheads,” she recalled – and through the galleries of the V&A. Two Vigeland pieces now sit in the V&A collection – a steel-feathered necklace and a coiled bracelet – pieces that, as the museum’s curators note, highlight the artist’s ability to combine “extraordinary fluidity and wearability.”

And yet, Malm Brundtland observes that she has never seen Vigeland “wearing one of her beautiful, magical necklaces herself. As if, in her imagination, they are more sculptures than pieces of jewellery.”

Tone Vigeland, Muster IV-2, 2016. Steel. (Photo: Vegard Kleven © Punkt Ø)

Vigeland’s shift to sculptural works and installations came in the mid-1990s after the directors of Galleri Riis in Oslo suggested that she make an object for exhibition. That single piece – a mesh of copper, nickel-plate and bronze as uncanny as a mass of primordial moss – was followed by a solo show. A permanent refocus, away from jewellery design to sculpture, followed suit. “She had that ambition,” notes Espen Ryvarden, co-director of Galleri Riis. “She just needed a nudge.” The gallery has represented her ever since.

As with her jewellery, Vigeland’s sculpture often echoes natural phenomenon: trees in the wind, a cascading waterfall, the murmuration of a flock of birds. For one series she hammered shrouds of lead around stones, for another she formed beetle-like creatures from doodles of steel. They are all labour-intensive pieces and often large; some involve the participation of the buildings that house them, with metal tendrils plugged into the surface of walls. They fit organically – yet strangely – into their surroundings, just as her jewellery flows on the human figure but retains an alien essence. The sculpture at Kistefos is of a piece with this vision: it fits in the specific corner of the sculpture park, weaving between silver birches, as if nestled in the nape of a neck. And yet it is also a strange metal movement in a very still space.

Throughout the artist’s career, there has been little distinction between her home life and studio work – both coexist in the arts-and-crafts house built by her grandparents in 1908 in the quiet villa-dotted neighbourhood of Slemdal on the fringes of Oslo. Her grandfather’s extraordinary mausoleum, Tomba Emmanuelle, sits on the neighboring plot.

Tone Vigeland, Bracelet, 1 of 2, 1992. Silver, Vestlandske Kunstindustrimuseum, Bergen (Photo: Guri Dahl)

Everyday life and artistic concepts are inseparable in Vigeland’s quiet haven. Malm Brundtland remembers an occasion when she arrived at the artist’s home proudly sporting a contemporary necklace by another designer, a silver piece formed from several small leaves which together gave off a rustling sound. “Tone opened the door, stared at my necklace and quite abruptly said that if I wanted to come in the necklace should – immediately – be hung in the hallway. It could be picked up when leaving her house,” Brundtland recalls. “For her it was impossible to allow things into her house that violated her aesthetic sense, which this necklace obviously did. Art was the be all and end all.”

Sculpture 1, 2022 is now on view at Kistefos Museum

Works by Tone Vigeland are available from Galleri Riis in Oslo and are on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

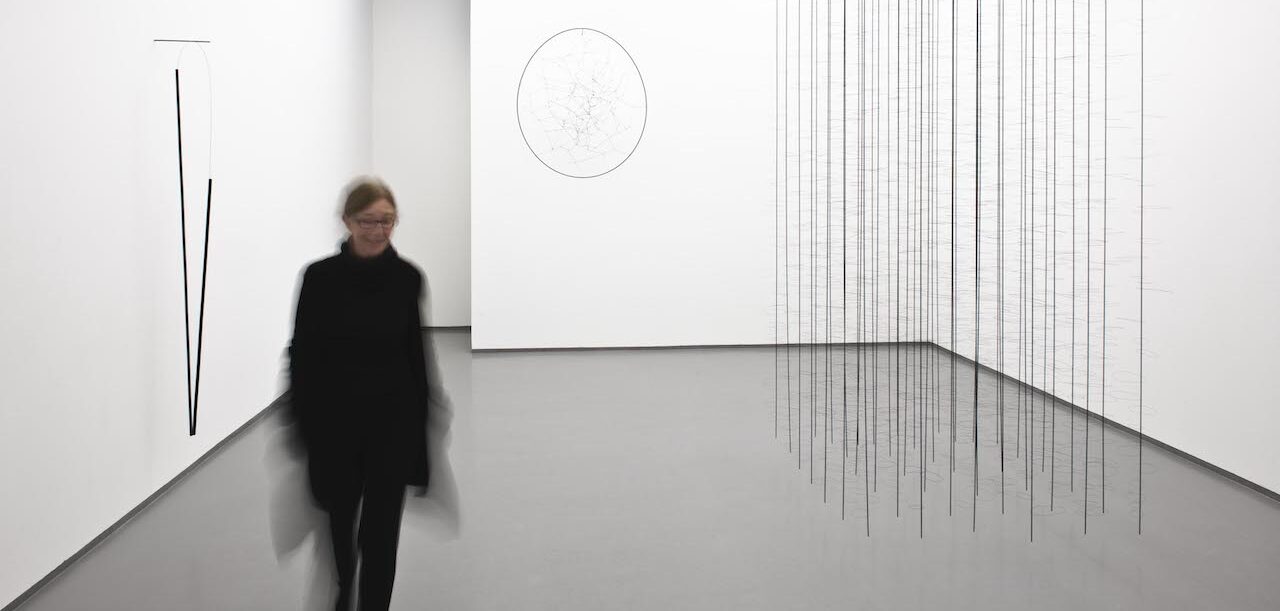

Top: Tone Vigeland in Galleri Riis in 2011 (Photo: Guri Dahl)