As London Design Festival prepares to open, Giovanna Dunmall surveys Norway’s ‘Re(New) Generation’ collection which draws on the ancient and organic as well as the latest technology and artistic trends.

At this year’s London Design Festival, the collective digital design gallery Adorno showcases eight collections, from different countries, under the theme ‘Designing Futures’. The “(Re)New Generation” collection delivers the visions of 10 creatives who curator Kirsten Visdal believes represent the next generation of Norwegian art and design and who effortlessly combine ancient materials with digital techniques and age-old craftsmanship with machine tools. “The collection consists of stones that are millions of years old, stools that look like twisted branches shaped by wind and weather, and wood that has been carefully shaped into furniture designed to last for a very long time,” she says. “It shows a mix of free interpretations in which traces of the hand are prominent. The objects have a modernity about them even though the inspiration is taken from previous techniques, methods and tradition.” She calls the selected designs “wild, beautiful and brave”.

“It feels good to take a piece of nature and design products based on intuition.”

Norway has a humble heritage in the field of design compared to neighbouring heavyweights Denmark and Sweden. Historically, Norway has been characterised by more pragmatic factors, such as its strong heritage of fishing and agriculture and its close relationship with raw materials and the natural world. Some constants permeate all Nordic design, however – quality, functionality, simple materials and minimalism – and larger manufacturers and brands in Norway selling simple and streamlined pieces have made inroads in recent years.

The new generation of designers is different, says Visdal, more experimental, and keen to forge its own path. Perhaps surprisingly, working with their hands is one way of doing that. “It may be a counter-reaction to a technological and partly uncertain world, but it feels good to take a piece of nature and design products based on intuition, and let the material help find a final expression,” she says.

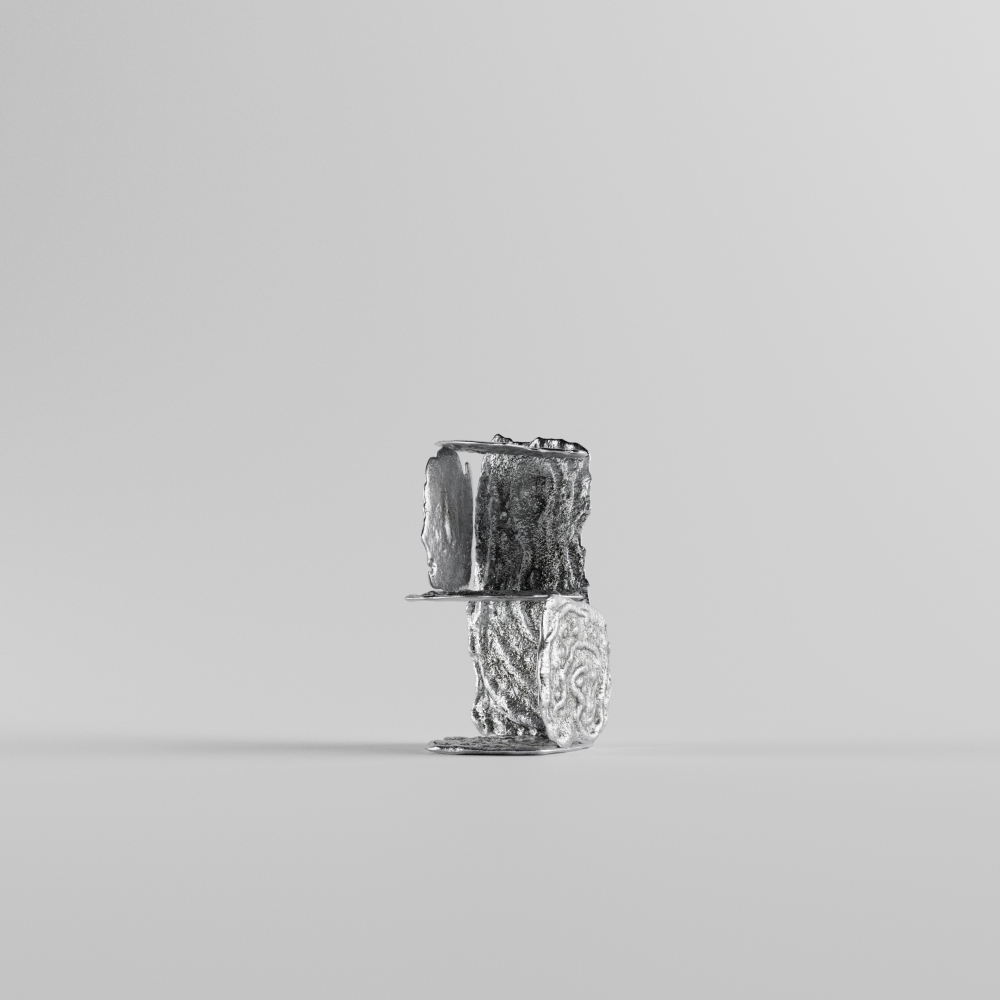

One designer working in just such a materials-led and intuitive way is Oslo-based Ali Gallefoss, who is showing a side table shelf in cast aluminium as part of Adorno’s Norway capsule collection. “I noticed that the shape of mass-produced materials limited me when designing, and I wanted to break away from that and create my own shapes.” Gallefoss was able to persuade the only foundry in Norway that casts aluminium to make his project in his own idiosyncratic way.

“Usually, you make a positive and negative mould and cast the piece in oil bonded sand, which is a very precise and predictable process,” he explains. “In this project, I made my own sandbox from the sort of timber pallets that you normally use to create flower and plant beds. I filled the box with fine dry sand, moved the sand around to create obstacles and then poured liquid aluminium into it.” Watching the metal run through the mould is exciting, he says. “If I see a hole created by the unexpected path the metal takes through the mould, I decide whether to pour more to close the hole or stop pouring to keep it. This is a very intuitive and instinctive way of working.” The objects Gallefoss creates are then welded together to create objects. These pieces became a side table but had he made them on a different day they would have ended up as something completely different, he says.

Another creative included in Adorno’s Norwegian collection working in a very personal way is Oslo-based Mingshu Li. Her White Tubes’ Form-(2) is made of porcelain using extruding and coiling techniques. “All my works focus on two key ideas: holes and airflow,” she says. “Holes play a similar role as the blank space in a painting or the pauses in a piece of piano music, they have as much shape and meaning as solid mass.” Her work is about expressing the Chinese life force that is Qì, she continues. “It symbolizes breath, material energy, and energy flow. So, I’m working with holes to represent airflow – not only in a kiln but also when displayed in a physical exhibition space.” Li uses a hand-held clay extruder that creates air bubbles as the clay passes through it. She leaves these holes and imperfections in the finished work.

Some of the designers involved in the exhibition may seem on the surface to be making more conventional Nordic objects, but they are nevertheless still pushing boundaries. Studio Sløyd’s Furuhelvete collection celebrates the different characteristics of pine wood, a timber that is available in abundance in Norway but the use of which is in decline, in part due to it being considered unfashionable and outdated.

“We wanted to give the material a bigger canvas.”

The piece they are showing, a three-legged stool called POM, is made using a CNC machine (a computer-programmed tool and platform) but given an appealingly chunky profile, the opposite of the streamlined look we usually associate with Nordic design. “We wanted to give the material a bigger canvas,” explains Herman Ødegård of the studio. The collection aims to encourage designers to use local instead of imported timber and to show how a wood that is often considered ‘too soft’ for making furniture can be both robust and aesthetically pleasing.

Also banging the drum for sustainable local timber is Christian Udjus and his green furniture company Bergskog. Udjus resigned from a job as a brand manager in 2016 and went to live in a village in the Telemark taiga – or snow forest – in southern Norway with his family. This is where he makes some of the Nordic region’s most sustainable furniture. Made from local wood, mainly birch, felled by Udjus and his colleagues, his pieces are joined without the use of a single screw. The Bergskog collection currently consists of two chairs (one of which, Naess, is part of the Adorno exhibit) and a sideboard. Customers can pick from different types of birch, choose upholstery materials and select a specific finish which, notes Udjus, making buyers more likely to look after and keep the piece for generations.

Many of the creatives involved in the showcase believe that the scene for Norwegian design is evolving. “It has been quite bland in the past but a lot has happened in the last five years,” says Gallefoss. The two members of HLÍN Studio, who are showing a playful table made from Jesmonite (a cast concrete substitute) called Edgy Object, agree. “It used to feel very traditional and safe, but it seems like designers are stepping out of their comfort zone more and experimenting with different materials and more unconventional shapes,” says studio partner Julia Conley.

New art and design galleries like Pyton in Oslo, which champions emerging designers and artists, and festivals like Designers’ Saturday, during which new products are launched, have been instrumental in this transformation. As have ongoing and “well-functioning government support schemes” says Visdal. The support and the fact that arts education is free was a big driver for Li to come to Norway from China. “In this country you don’t have to come from a rich family to become an artist,” she says. “Norway has a democratic approach to the arts; individual artists receive stipends from the government and the more traditional grants and funding go towards museums, artist-run spaces and galleries.”

“More daring and playful forms of expression.”

Above all, there is more diversity now in the design scene, says Gallefoss. “It contains both arts and crafts, small scale production and commercial production.” This may be in part the result of an arts education system that encourages young artists and designers to explore various research directions and art forms and focus more on interdisciplinary practice, suggests Li. And as multiculturalism has become more entrenched, the scene has become more international and influenced by different cultures and lifestyles. “This has led to more daring and playful forms of expression,” says Visdal.

Despite the obvious difficulties, the last 18 months have had upsides for many creatives in Norway, she continues. “They have been given peace of mind to explore and be innovative.” Both designers and manufacturers are hungry and ready for a return to a more open society however. “The most difficult part of Covid for us has been the lack of networking and furniture fair exposure,” says Tim Knutsen of Studio Sløyd.

But the lack of international contact can also be seen as a positive. “We have been hiking more; vacationing in our own country instead of travelling abroad, and I believe this gives us a deeper connection to the land,” says Gallefoss. “With this, has followed a greater awareness and care for nature. I think this landscape, which shifts in scale and appearance from soft cornfields to calm lakes and raw and brutal mountains has inspired, and will continue to inspire, the way we create objects, furniture and art.”

The Re(New) Generation virtual exhibition of Norwegian design runs from 18-26 September at www.adorno.london

Participating designers: Ali Gallefoss / Anna Maria Øfstedal Eng / Atelier Kaja Dahl / Bergskog / Edvin Klasson / HLÍN Studio / Løvfall / Mingshu Li / Studio Sløyd / Vilde Hagelund

Top photo: The Norwegian design virtual exhibition (Photo: Cielo Alejandra | ADORNO)