Norway’s contribution to this year’s London Design Biennale explores how the country’s enduring relationship with water has fuelled a sustainable and inclusive approach to design. Ahead of a virtual conference surveying its theme, Amy Frearson takes a look at the projects on show, from an underwater restaurant to a sightseeing boat with a difference.

“Water is never far away in Norway,” says Anne Elisabeth Bull of Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA). She’s not wrong. With one of the longest coastlines of any country in the world – an estimated 100,000 km, if you include all the islands – it is a place where fjords, lakes and the ocean have shaped all aspects of the landscape and lifestyle. But recently, as Norway moves towards a low-carbon economy and the world gears up to tackle the climate crisis, these huge bodies of water have started to take on new meaning. Not only are they a source of renewable energy – one that has made Norway a world leader in hydroelectricity – but they also offer opportunities for people to reconnect with nature.

“Ever since the Viking Age, water has been giving life to all Norwegians,” says Bull. “But before, the ocean was solely for necessities, such as transport, fishing and, in recent years, oil and gas, whereas today the ocean offers a wide range of experiences and innovations.”

It was this shift that prompted DOGA’s curatorial team, led by Victoria Høisæther and Jannicke Hølen, to explore ocean-centric architecture and design as their theme for the third edition of the London Design Biennale. Asked by the biennale’s artistic director, stage designer Es Devlin, to explore the idea of ‘resonance’ in an age of crisis, they wanted to show the power of water as a framework for sustainable lifestyles. With this exhibition, ‘The Ripple Effect: Connecting People and Nature’, the goal was to communicate how living and designing in harmony with the natural world offers benefits to individuals and society, as well as the environment.

The Soria Moria sauna in Telemark (DOGA)

Of course, as a result of the pandemic, things didn’t go as planned. With the biennale postponed by a year and the ongoing uncertainty of travel restrictions, Norway became one of six participants that made the difficult decision to drop their physical exhibition in favour of a digital approach. While the original plan was to create immersive installations, Norway’s presence in the biennale’s exhibition spaces at Somerset House has been reduced to a five-minute film screening. Walking through the show, where there are plenty of other things to catch the eye, you could be forgiven for missing it.

Perhaps anticipating this, the curators have also organised a virtual conference that will delve deeper into the content. They believe this format may in fact reach a wider audience than would have been possible with a purely physical exhibition. Whether or not that’s true, what is certain is that there’s a lot more to the featured projects than there’s time for in the film, so it can only be a good thing that visitors have the opportunity to get to know them better.

Under restaurant, designed by Snøhetta (DOGA/Ivar Kvaal)

Among the projects is one that many will be familiar with already. Plunging more than five metres below sea level, Under is an underwater restaurant that offers a rare insight into what goes on beneath the water’s surface. Designed by Norway’s best-known architecture studio, Snøhetta, this incredible feat of engineering consists of a 34-metre-long concrete tube that extends down from the coastline like a giant periscope. At its lowest point, an 11-metre-wide panoramic window punctures the concrete structure, giving diners a once-in-a-lifetime experience of marine life. “It speaks to everybody, even if you only see it in pictures,” suggests Kathrine Ubostad, who co-owns Under with her husband Stig, Stig’s brother Gaute, and his wife, Hege.

Under restaurant at Båly , Norway, designed by Snøhetta (Ivar Kvaal)

It is not actually this spectacle that the curators want to highlight, but rather the way this sub-aquatic building and its owners respect the surrounding environment and community. The concrete structure was purposely left rough on the exterior to attract ocean flora and fauna like limpets and algae, forming an artificial reef that helps to naturally clean the water. Cameras and sensors mounted around the building facilitate extensive marine research.

Meanwhile the restaurant serves a menu that combines bycatch – the unwanted fish or marine life caught by fisherman – with locally foraged ingredients, in order to reduce its environmental impact, and chefs have even been reaching out to local residents to discover the regional traditions for preserving ingredients for the winter season. This feels especially pertinent at a time when the food industry, and particularly fishing, is increasingly coming under fire for unsustainable practices.

Under restaurant executive chef Nicolai Ellitsgaard foraging for seaweed (photo: Under restaurant/DOGA)

As Bull points out, a building like Under can’t be judged on architecture alone; it has to have a positive and meaningful impact on its surroundings in order to be deemed successful. “The way a building is used is everything,” she says. “When it’s done right, and in an inclusive manner, you can feel it. It has the ability to change people’s lives.”

This concept of inclusivity has been at the heart of many design projects to come out of Norway in recent years, and was also a central focus in both of Norway’s previous two London Design Biennale contributions. This has a lot to do with a universal design action plan ratified by the Norwegian government in 2005, promising to make infrastructure – public buildings, spaces and transport – across the entire country accessible to all by 2025. But it’s also intrinsic to Norwegian culture in a way that it isn’t to many other nations. For instance, access to land in the UK is heavily restricted, yet in Norway there is ‘freedom to roam’, which means that everyone has a right of passage through uncultivated land in the countryside.

Legacy of the Fjords (DOGA)

An inclusive design approach is particularly evident in The Legacy of the Fjords, an electric-powered catamaran created by Norwegian tourist company The Fjords, with the help of ship builder Brødrene Aa. With wide, zigzagging pathways into its hull, not only does this unique sightseeing vessel allow wheelchair users to access its upper deck, it also creates more space for all passengers to enjoy the sights. For those who prefer to stay indoors, the spacious interior lounges feature oversized windows, offering good visibility to those seated or standing.

Interior of Legacy of the Fjords (DOGA)

It means that everyone journeying on this boat, which travels between the UNESCO-listed fjords of Flåm and Gudvangen, can enjoy the experience without compromise. “That’s what’s so great about universal design,” suggests Torstein Aa, the industrial designer at Brødrene Aa behind the design. “You create something for certain people, but everybody else gets to benefit.” These benefits extend to the environment – thanks to the use of electric power, this vessel is both silent and free of emissions, making it as sensitive to the fragile ecosystems of the fjords as it is to its passengers.

Soria Moria sauna in Telemark (DOGA)

A different form of inclusivity can be found at the Soria Moria sauna in Telemark. Projecting out over the waters of Lake Bandak, this small wooden structure was designed with tourism in mind, but has ended up becoming a landmark for the community. In a place where winters can be very lonely and isolating, it offers a space where locals and tourists alike can reconnect with each other, and with nature.

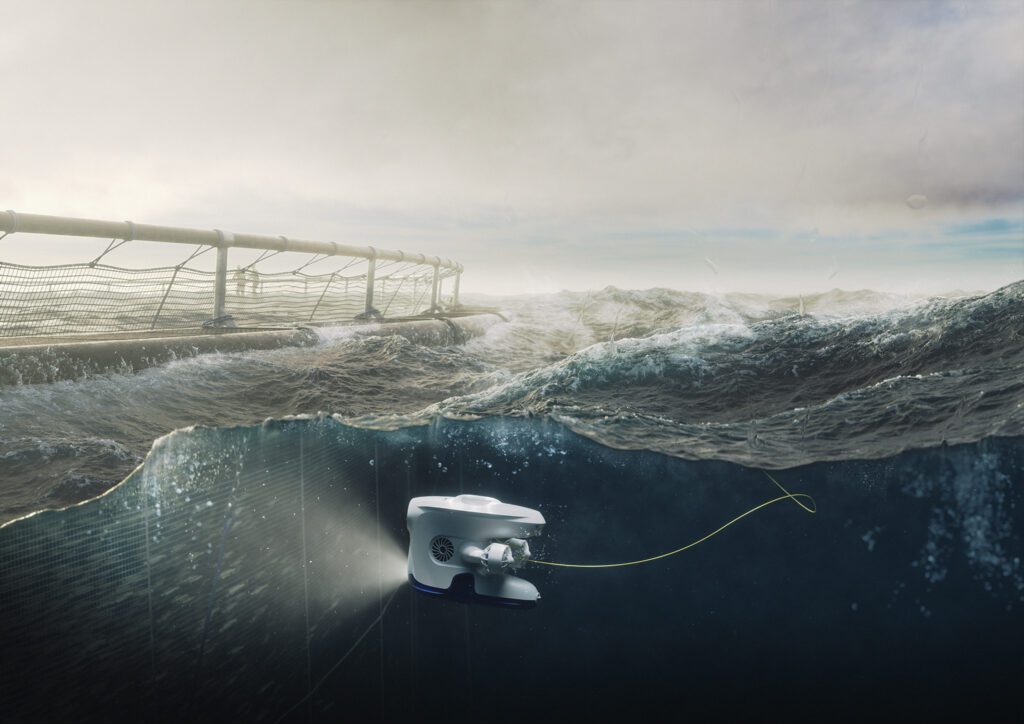

Brim Explorer (DOGA)

The final project on show, Brim Explorer, shows that technology can play a role in bringing people, inclusively, closer to nature. This underwater drone can dive up to 150 metres underwater, and it shares its discoveries through a live feed you can watch on your smartphone or tablet.

Brim Explorer (DOGA)

A common thread running through all of these projects is a question about sustainable experiences. Can tourism have a positive impact on people and the environment, as well as supporting local economies?

The message here is that yes, they can. DOGA’s Jannicke Hølen talks about the idea of sustainability as being “a three-legged-chair”. She states: “Good design needs to be meaningful for people and everything around us. It needs to be valuable for people and environment, but also in a business sense. That’s the ripple effect.” Even told through a digital format, it’s a strong argument that should – to quote the biennale theme – resonate with us all.

For more information visit London Design Biennale

The Norwegian digital event takes place from 1.30pm BST on 17 June 2021. Register free here: Norway | London Design Biennale

Top photo: The Soria Moria sauna in Telemark (DOGA)