For centuries trees have cast a spell on Norwegian artists, as illustrated by the spring willows and winter birches on view in a new book on the painter and gardener Nikolai Astrup. Taking an art-historical ramble through a particularly Nordic obsession, Anna McNay discovers a tangled world of tree trolls, forest fires and future libraries.

For Norwegian artists – visual, but also writers and composers – the construction of a national identity has always been a central tenet of their vocation, both during and following centuries of foreign rule, when Norwegian culture was well-nigh quashed. And the tree forms the backbone of that cultural character.

In Norse mythology, not only were the first man, Ask (ash), and woman, Embla (elm), created by Odin, the father of the gods, by his breathing life into two logs, but, in the concentric architecture of pre-Christian legends, there were three rings: Asgard, the inner ring, home to the gods; Midgard, the middle ring, home to humans; and Utgard, the outer ring, the realm of giants and trolls. This layered structure, suspended over the nothingness of Ginnungagap, was held in place by a giant ash tree, Yggdrasil.

Although the country’s identity was all but in place by the time Nikolai Astrup was born in 1880, his work – celebrated in the new monograph Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway – was influenced by his forebears. As critic Jonathan Jones notes, the artist’s work possesses a “primitive and ancient quality”. His pictures are stirred by magical realism and steeped in folklore. Astrup himself once claimed: “I, perhaps, am one of this country’s painters closest to the soil.”

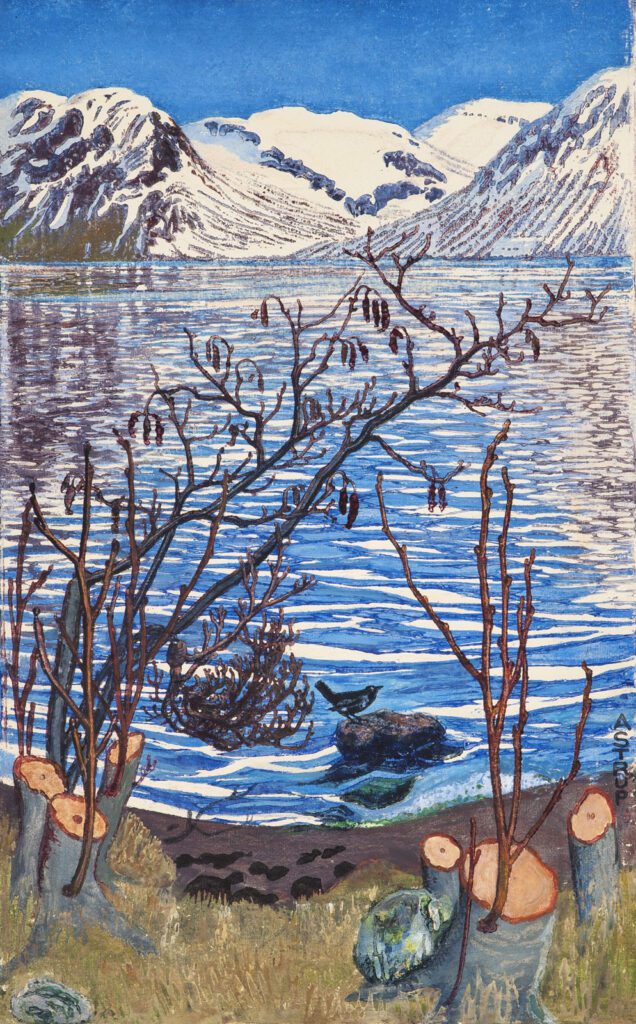

Nikolai Astrup, Bird on a Stone, woodblock, c. 1905–14; print, by 1914, color woodcut with hand coloring on paper. Private collection.

Astrup was the eldest son of eleven children born to a pastor in the Jølster region of west Norway. His work comprises intensely-coloured paintings and intricate woodcuts, the latter using a technique similar to the Japanese ukiyo-e, with a different block of wood for each colour and added brushwork to create texture to the surface.

Apart from a period spent studying art in Kristiania (modern-day Oslo) and Paris, Astrup spent all his life in Jølster, and his works betray the intimacy of an insider. Between 1898 and 1909, he filled three notebooks with motifs drawn from Jølster’s physical features, weather conditions, vegetation, atmosphere and qualities of light. And trees, of course. He was not only an artist, but also a horticulturalist. His later works were tied in with the establishment of his terraced farmstead at Sandalstrand (now the Astruptunet museum). The works he created there would still feature trees, but they were portrayed simply, as part of nature and a home.

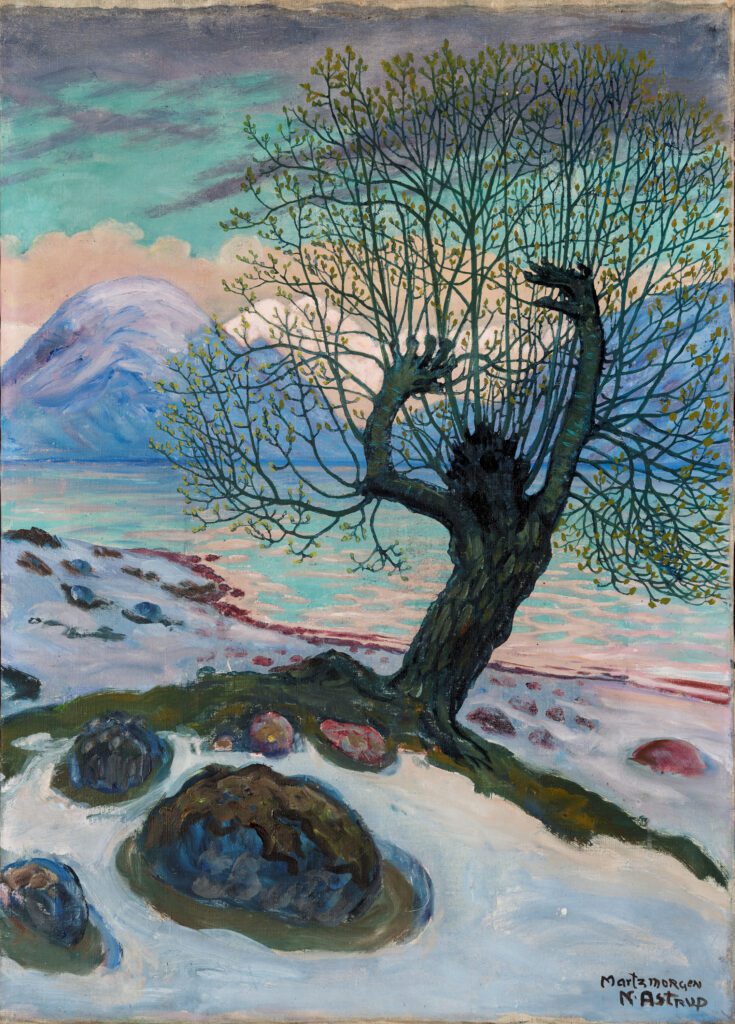

Astrup would repeatedly return to a motif, turning woodcuts into paintings and vice versa. An example of this is the woodcut Spring Night and Willow (1917), with its various subtly different hand-coloured prints. Unhappy with these, Astrup decided the theme of the anthropomorphised willow tree, with hollow eyes and mouth agape, arms with six-fingered hands, and many fresh shoots like Medusan-hair, was better-suited to a painting, and thus A Morning in March (circa 1920) was created.

A Morning in March, 1920, by Nikolai Astrup (Dag Fosse/KODE)

Astrup used one of his own trees as a model and helped create its troll-like appearance through the practice of pollarding, which encourages the growth of fresh twigs in early spring. He referred to this tree as the “willow goblin”.

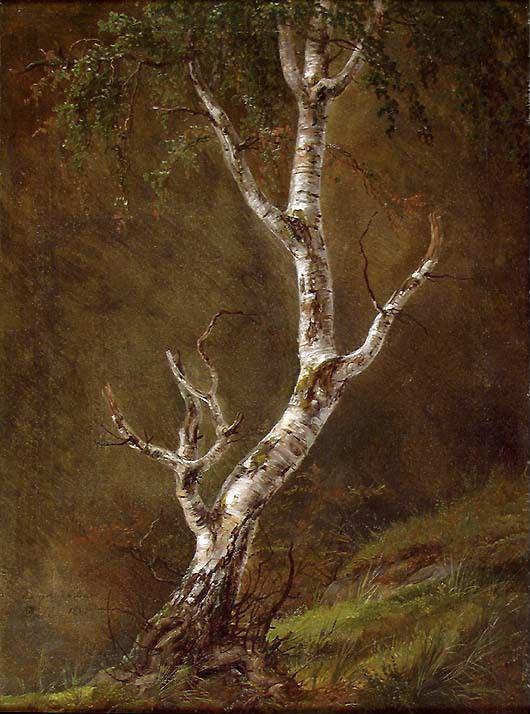

But Astrup was just one in a long line of Norwegian artists to use the tree, symbolically and literally, as a motif. The so-called father of Norwegian landscape painting, Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857) spent most of his life outside of Norway, where he acquired significant renown, but he painted visions of his “northern Arcadia”, often rendered idyllic, frequently melancholic. He lived and worked closely with Caspar David Friedrich in Dresden but remained adamant that landscape painting should not just depict a specific view, but should also say something about the land’s character. His Birch Tree in a Storm (1849) is a fantastic example of chiaroscuro, as well as of the strength (of character) of the tree, with the dappling of light on its battered leaves and straining trunk.

Study of a Birch Tree by Johan Christian Dahl (Norwegian National Museum)

Thomas Fearnley (1802-42), a pupil of Dahl, placed great emphasis on the painting’s architectural structure – frequently framed or scaffolded by trees. A notable work is Old Birch Tree at the Sognefjord (1839), in which two figures beneath the tree stare into the distance across the lake to the mountains. It has an element of the Friedrichian sublime, albeit set in a more friendly, less isolated, setting, emphasised by a vivid orange sunset and the protective tree. Interestingly, in the similarly composed, but daylit, Landscape with Traveller, of the same year, the figure is solitary, but there are two trees, raising the question: might humans and trees be interchangeable?

Old Birch Tree at the Sognefjord, 1839, by Thomas Fearnley (Norwegian National Museum)

Fearnley’s lone birch tree, which became something of a symbol of Norway, was later developed by Eilif Peterssen in his Summer Night (1888), in which the birch is depicted fallen across a sheet of water. Art historians have described this felling of the tree as a movement, conscious or otherwise, away from idealised nationalism to the reality of a countryside that any Norwegian might encounter.

Realism and the imaginative sublime continued to coexist, however, in the work of Peder Balke (1804-87) and August Cappelen (1827-52), best known for their dramatic and desolate compositions (with many a broken tree). Their generic titles and locations lay the focus on the grandeur of nature and man’s comparative insignificance. Cappelen’s Extinct Primeval Forest (Decaying Forest) (1852), discovered unfinished on his easel at the time of his death, aged just 25, depicts a scene of toppled trees and decaying beauty. Yet one tree in the centre seems to remain green, youthful and sprouting a new branch – perhaps a sign of regeneration and hope?

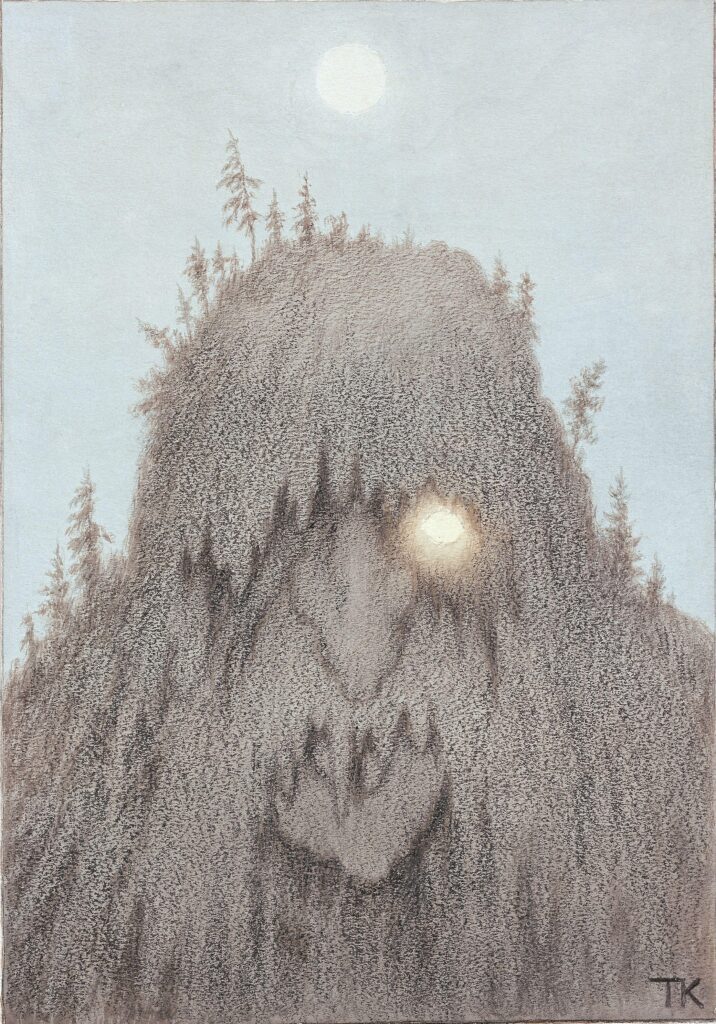

Forest Troll by Theodor Severin Kittelsen (Norwegian National Museum)

The artist synonymous with the Norwegian folk movement is Theodor Severin Kittelsen (1857-1914), who found great success illustrating fairy tales and legends, with princesses and trolls, many of whom grew out of anthropomorphised trees. “It is not the dramatic ‘effects’ of nature that I am concerned about,” Kittelsen said in 1904. “It is the mystical aspect of it, the calm, the secretive…” His naïve style was to influence Astrup.

Few artists successfully bridged the naturalistic and symbolic-visionary styles, but Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was one. Although better known for his figures, he did also turn to the motif of the tree, both in his art nouveau-influenced woodland scenes of the turn of the century, and, for example, in The Yellow Log (1911-12), vibrant with its complementary yellow and purple. In this, the horizontals and verticals of trunks felled and trees still standing suggest the immensity of the forest beyond the frame, and combine the idealism of Fearnley and the realism of Peterssen.

Contemporaneous with Munch, Harald Sohlberg (1869-1935) – whose painting Winter Night in the Mountains (1914), with its bare-branched trees framing the composition in a manner akin to Fearnley, was proclaimed Norway’s ‘national painting’ in 1995. Sohlberg was fascinated by the works of both Kittelsen and Astrup. Nevertheless, he sought to avoid the fantastical character of their imagery, referring instead to human presence in the landscape through such motifs as roads and telegraph poles. In The Country Road (1905), the upright trees, matching the verticals of the poles, provide another example whereby they might be interpreted to suggest an absent human presence.

It is not just two-dimensional artists who have been drawn to trees: the sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869-1943), who, like Munch, largely focused on the figure, has one central ‘installation’ at the sculpture park in his name in Oslo, namely a fountain surrounded by a series of sculptures of entwined figures and trees (usually referred to as the ‘tree groups’). Here, people literally intermingle and interchange with the trunks.

Slash & Burn #15 by Terje Abusdal. Lindalstorpet by Lake Skasen, one of the first farms to be settled in Finnskogen. Grue Finnskog, 2016 (courtesy of artist)

And the tree persists in contemporary works. Some respond to older paintings, such as Lars Korff Lofthus’ Neon Bjerk i Storm (2009), referencing Dahl’s birch, whereas others respond to other historical sources, such as Terje Abusdal’s photographic series Slash and Burn (2017), which captures the mysterious world of the ‘Forest Finns’, a group of farmers who left Finland in the early 1600s and settled in a forest belt along the Norwegian-Swedish border. Here, they set fire to the woodland to create fertile soil for their crops. “These customs are long since gone,” says Abusdal, “but there is something ethereal lingering among the trees.” His work is a fabulous alchemical mixture of fact and fiction, in which – taking elements from the Forest Finns’ culture – he even set light to a number of his images, with eerie results.

Even non-Norwegian artists have responded to the significance of the tree in Norwegian culture. The British artist Katie Paterson has used them as the material matter for her century-long Future Library project – or Framtidsbiblioteket – a public artwork that collects an original piece of writing by a popular author each year, from 2014 to 2114. They will only be read and published at the end of the project. One thousand trees have been planted in the Nordmarka forest outside Oslo to provide the paper to print a library of books in a hundred years’ time. Contributing authors include Margaret Atwood and Karl Ove Knausgård.

Evig din (Forever Yours), 2020, by Marit Solum Smaaskjær, gesso and pencil on canvas (photo: courtesy of artist)

Contemporary Norwegian artists have used a variety of mediums to express their inspiration by trees and forests. Marit Solum Smaaskjær works in drawing and painting to convey what she describes as “the adventurous experience of old forests”. For the past year, in particular, she has created portraits of trees in ink and felt-tip pens. For her, it is the mysterious which catches her attention: “Something strange, the light, something broken.” She uses the forest, with its endless variation, to depict everything from predictability to chaos.

Etterdønninger by Eigil Nordstrøm, acrylic on hessian (courtesy of artist)

Elsewhere, bare, haunting trunks populate the enigmatic paintings of Eigil Nordstrøm. “I grew up by the forest, enjoying the feeling of safety and permanence that trees gave me – in complete contrast to nature’s current state of emergency,” he says. That is the contradiction explored by Nordstrøm.

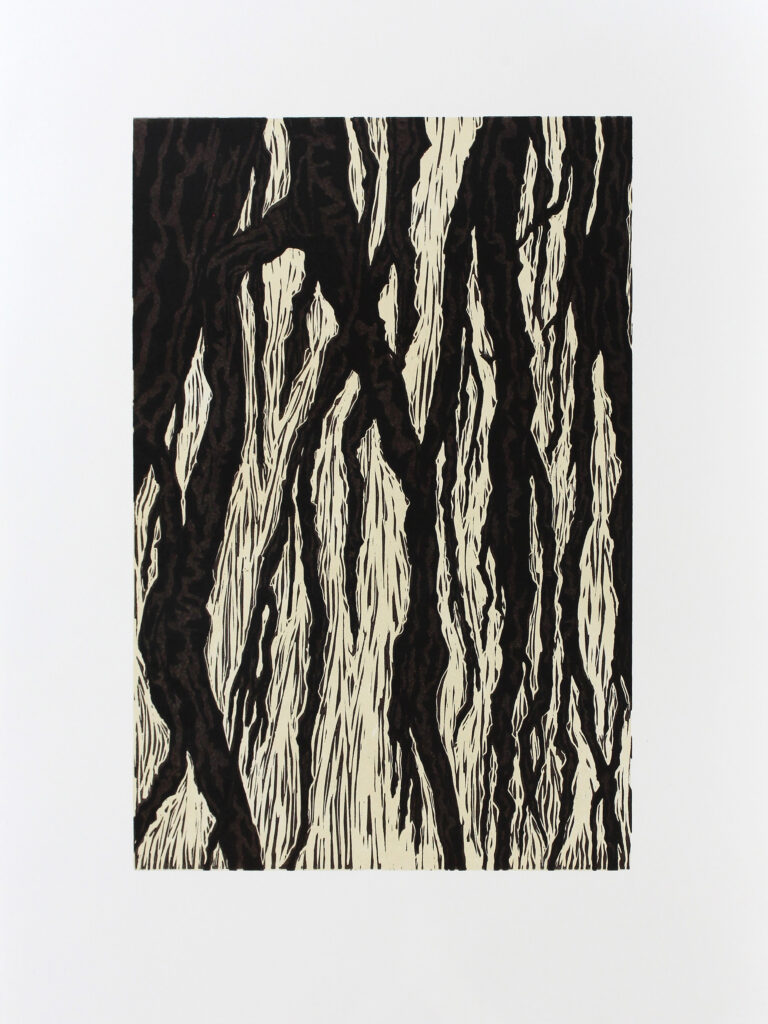

Rotskjelett (Root Skeleton), 2021, by Lena Sundnes, woodcut (courtesy of artist)

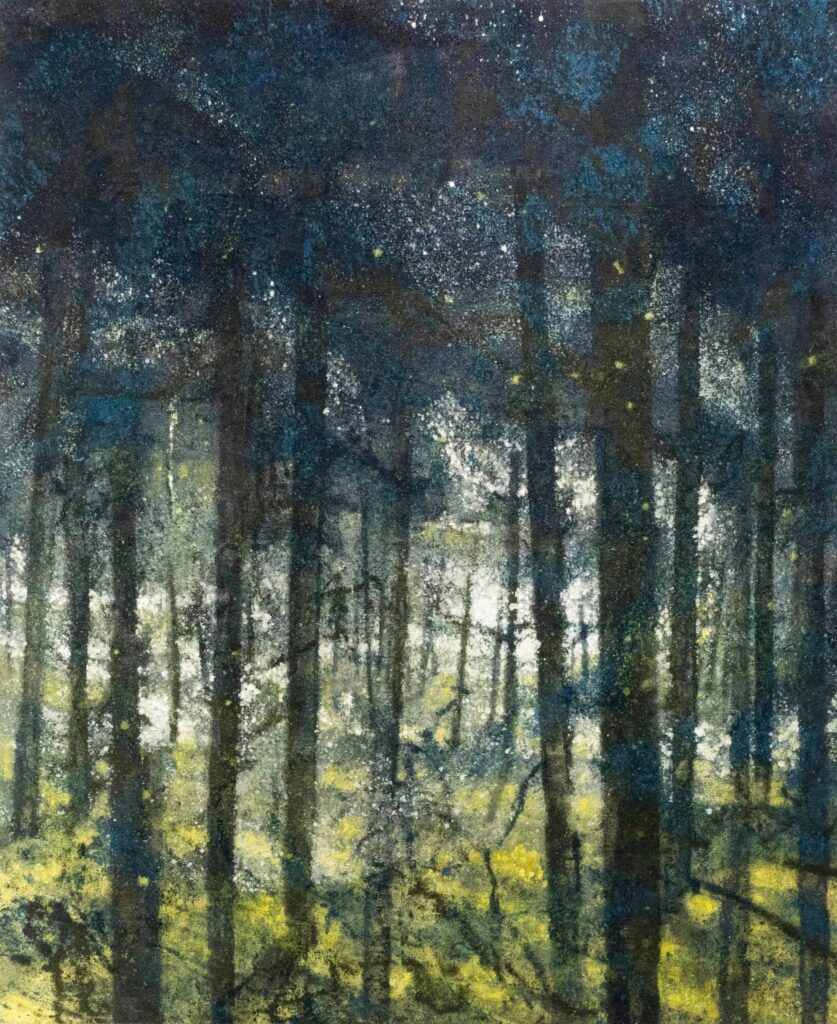

Lena Sundnes, meanwhile, is more concerned with the tree forms themselves, and with capturing them in a medium which reveres this – the woodcut, just like Astrup. Another artist intrigued by the natural arrangements is Anne Kathrine Stangeland, who makes often abstract – or abstracted – paintings, sometimes focusing solely on a tree’s interlocking branches.

“Trees appear as natural compositional elements,” Stangeland says. “Trees mean structures and grids, colours and shapes. Bent, fallen, reaching for light, they can turn out as portraits loaded with meaning, or, on the contrary, mean nothing, painted simply as they are.”

Natural chaos, 2015, by Anne Kathrine Stangeland (courtesy of artist)

And so, we come full circle, back to Dahl’s earliest birch painting and Astrup’s works from Sandalstrand, where, despite the rich mythological and symbolic cultural associations of the tree motif seen throughout Norwegian art history, sometimes it is enough for a tree to simply be a tree.

Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway edited by MaryAnne Stevens is published by Yale – complementing the exhibition of the same name at the Clark Institute of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts (until 19 September 2021)

Tree-filled works by many of the artists in this article can be found on the Norwegian National Museum collection site

For more information on the contemporary Norwegian artists mentioned visit their respective sites: Terje Abusdal / Lars Korff Lofthus / Marit Solum Smaaskjær / Eigil Nordstrøm / Lena Sundnes / Anne Kathrine Stangeland

For information on Katie Paterson’s project visit Future Library

Top Photo: Between the branches, 2015, by Anne Kathrine Stangeland (Photo: the artist)