Thin air, precarious roads and resilient locals feature in High, Erika Fatland’s thrilling account of her Himalayan adventures. Travel, she explains, is a balancing act between preparation and improvisation.

In High, adventurer and author Erika Fatland chronicles her journey across the Himalayan valleys – through parts of Pakistan, India, Bhutan, Nepal and China – visiting villages, outposts and communities that continue to survive against the elements and constant poverty and who have endured the various historical, political and ecological dramas that continue to shape this extraordinary high-altitude landscape.

Fatland’s previous books Sovietistan and The Border – both shortlisted for Stanford Travel Writing Awards – were travelogues of the countries along Russia’s fringes: the five ‘Stan’ countries, and the 14 countries with direct borders on to Russia. Her travels for those books have taken her from the Caucasus to North Korea, and, most movingly in light of the current war, parts of Ukraine.

National Geographic stated that Fatland is “shaping up to be one of the Nordics’ most exciting new travel writers.” As High is published in Britain (published by MacLehose Press, translated by Kari Dickson), Fatland talked to Norwegian Arts about dusty mountain roads, matriarchal kingdoms and being a terrible packer.

In parts of Nepal everything has to be carried up on tired backs (Photo: Erika Fatland)

What initially inspired you to make a journey through the Himalayas?

The short answer is [the Disney cartoonist] Carl Barks! In his famous story ‘Tralla La’ Uncle Scrooge suffers a nervous breakdown and urgently needs to go to a place where money does not exist. Donald Duck and his three nephews take him to an isolated community far away in the Himalayan mountains. Ever since I read that story as a five-year-old, I wanted to go to the Himalayas myself.

The longer answer is that the Himalayas is one of the most fascinating regions on Earth in terms of cultural and linguistic variety, biodiversity, mountains (obviously) and geopolitics.

How do you prepare for your trips and what special measures did the Himalayas require?

I normally don’t prepare much, as improvising usually works better most places than careful planning. When it comes to the tallest mountain chain on the Earth, however, planning is key. There are two main reasons for this. The first is the weather. Because of the extreme altitude, some roads and regions are only accessible during certain times of the year. The second reason is politics. Tibet, for instance, can only be visited as part of an organized tour, and the itinerary needs to be carefully planned in advance. There is no room for improvisation.

Erika Fatland (Photo: Tina Poppe/Kagge Forlag)

Does being Norwegian inform your travelling style and how you interact with people around the globe?

I’m not sure, but I definitely think it is an advantage to come from a small country that most people do not have strong opinions about. Sneaking into North-Korea under false cover would probably have been more difficult – and dangerous – for an American than it was for me. But small countries can be controversial too. After the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiabo in 2010, Norwegians did not receive entry permits for Tibet for many years.

What were the highs and lows on this journey?

The highs were all the interesting and friendly people I met on my way. The lows were the roads. I have no idea how many hours I spent in total on dusty, dangerous mountain roads, moving at an average speed of 15 kilometers per hours, but it feels like it must have been weeks, if not months.

Considering the current war in Ukraine, are Sovietistan and The Border snapshots of a vanishing moment in time?

All travel books are snapshots of specific moments in time. The world is constantly changing and this is the reason why it needs to be constantly rediscovered and why new travel books are always in demand.

High: A Journey Across the Himalayas Through Pakistan, India, Bhutan, Nepal and China by Erika Fatland, translated by Kari Dickson (Photo: MacLehose Press)

When I visited Ukraine in 2016 as part of the research for The Border, Russia was already at war with Ukraine and thousands of people had lost their lives. The war began eight years ago, when Russia annexed the Crimea and Russian-backed separatists started fighting in Donbas in 2014. This war never became a frozen conflict, as many experts had predicted, but as the conflict dragged on, it rarely made it to the headlines any longer and slowly the rest of Europe forgot about the war.

This pattern is repeating itself today: the war in Ukraine is slowly disappearing from the headlines. This is a very dangerous development, because it is exactly what the Kremlin is hoping for. The war will most probably last for very long and we cannot allow ourselves to forget about it or to get worn out.

How dangerous was it exploring as a solo woman in the Himalayas, compared to travelling through other regions?

Many people seem to assume that it is a disadvantage traveling alone as a woman, but I would say that more often than not being a woman is an advantage, and even more so on this journey in the Himalayas than on others. Where a male travel writer would only be able to talk to half of the population, I also get access to the women and their stories. Especially in Pakistan I often experienced being invited into people’s homes whereas my male guide and driver would have to wait outside of the house, out of sight of the women.

Can you tell us about one person encountered on your Himalayan journey who you think embodied the region?

It is impossible to choose only one. In Sikkim, I met a princess who no longer had a kingdom, because Sikkim was annexed by India in 1975. This is the story of the Himalayas in a nutshell – the small kingdoms have been swallowed by the big nations. Talking about kingdoms – in Yunnan I visited a place known as the Kingdom of Women, because among the Mosuo people, the world’s largest matriarchate, the grandmother is the boss and takes all important decisions.

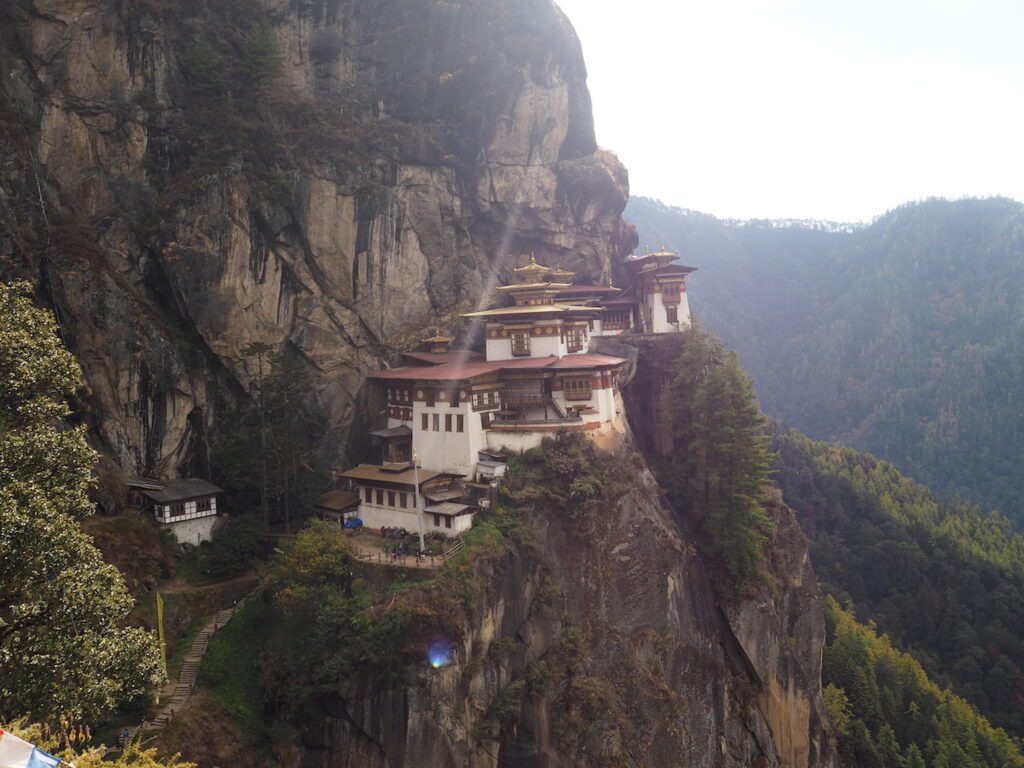

The Tiger’s Nest, one of the most sacred temples in the Himalayas, clings to the mountainside (Photo: Erika Fatland)

Are you now a world champion packer?

Not at all. I’m a lousy packer because I find packing incredibly boring, so I usually end up doing it at the very last minute and consequently pack too much, adding more and more, just in case, until the suitcase is full. My best tip is to travel with a small suitcase, that will force you to limit yourself, but then there is not much space left for shopping.

Grazing on a rare patch of grass in front of Everest (Photo: Erika Fatland)

Where are you right now and what is the view?

I’m in my apartment in Oslo, for a change, and am looking right at my brand-new globe and my long-suffering husband.

What are your secret Norwegian cultural tips, such as arts, sights, food?

One of my favourite activities in Oslo is to visit one of the floating saunas by the fjord. There are many new, amazing saunas to choose from and most of them offer drop-ins.

The food scene in Oslo has improved a lot over the last decade. Now you find the best sushi outside of Japan in Oslo. Try to get a table at sushi world champion Vladimir Pak’s Omakase – but you need to plan ahead, as there are only 10 seats available.

However, if you want to experience the real Norway, you have to venture outside of the capital. The north is my favorite region. Lofoten can be quite crowded in the season, but why not try Vesterålen a little bit further north? You will most likely have it all to yourself. Well, almost.

High: A Journey Across the Himalayas by Erika Fatland (translated by Kari Dickson) is published by MacLehose Press.

Erika Fatland will be speaking at Cheltenham Literature Festival on 8 October 2022.

Interested in staying in touch with Norwegian Arts and receiving news of upcoming Norwegian cultural highlights in the UK? Sign-up for our newsletter.

Read more articles on literature from Norwegian Arts.

Top photo: Decorative Pakistani trucks waiting for freight from China (Erika Fatland)