Less well known abroad than his contemporary Edvard Munch, Harald Sohlberg is nevertheless the artist behind one of the most loved paintings for generations of Norwegians. As an exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London – the first solo show of his work outside of Norway – marks the 150th anniversary of his birth, Norwegian Arts looks at the life and practice of the man who brought together the earthly and the infinite in his depictions of Nordic landscapes.

Click here to read more on Art, Craft & Photography from Norwegian Arts.

An Yves Kleinian blue is pierced by the bright, white light of the Evening Star. Beneath it, a range of white mountains rise and fall, like drapery, almost as if breathing, or foaming like the peaks of waves. In the foreground, eerie, bare and broken trees pierce the silent serenity, forming crosses and grave markers, as if amidst the rubble of a battlefield. A vivid expression of the sublime – although, perhaps equally a precursor of the uncanny shivers of the surreal – Winter Night in the Mountains (1914) (top photo) is arguably the most ambitious work of Norwegian artist Harald Sohlberg (1869-1935), and one of the best-known and most popular works in the National Museum’s collection in Oslo. It remained his obsession for 14 years, and he produced many versions in his attempts to capture exactly what he wanted.

“Denying the influence of other artists on his work, and attributing the origins of his ‘artistic awakening’ to his own psyche, his oeuvre unites elements of Romanticism, Naturalism and Symbolism, always drawing on the Nordic landscape and its vast potential to depict both the earthly and the infinite.”

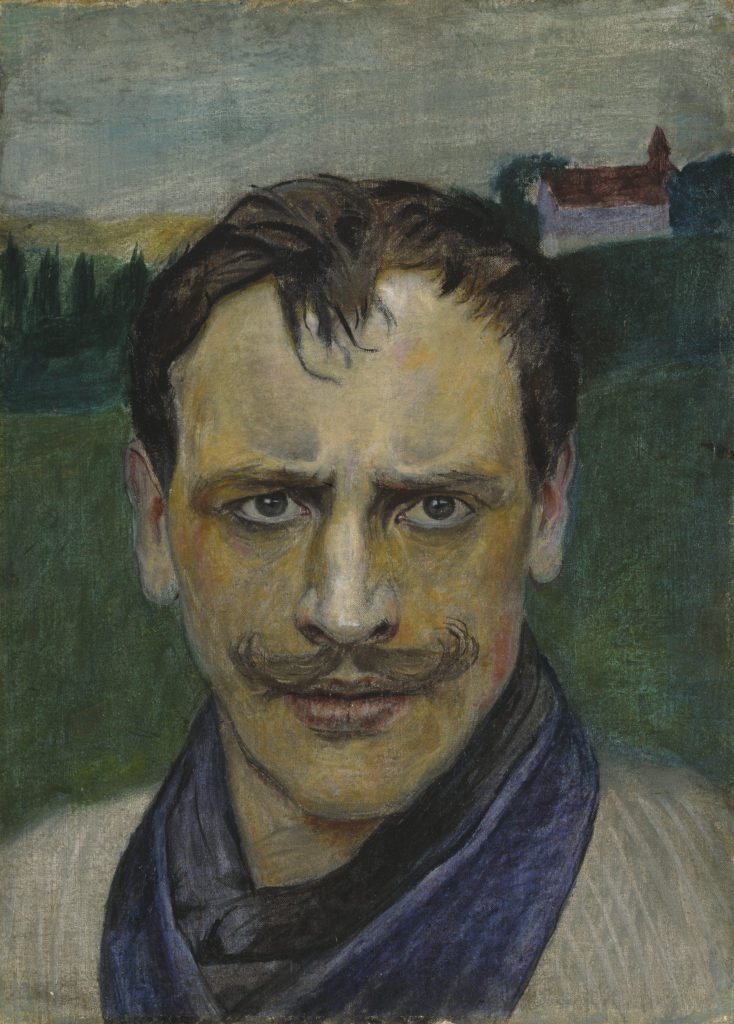

Although less well known outside of his home country than his contemporary Edvard Munch, Sohlberg is nevertheless being described by Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, as ‘one of the greatest masters of landscape painting in the history of Norwegian art’. Denying the influence of other artists on his work, and attributing the origins of his ‘artistic awakening’ to his own psyche, his oeuvre unites elements of Romanticism, Naturalism and Symbolism, always drawing on the Nordic landscape and its vast potential to depict both the earthly and the infinite. As Dario Gamboni describes in his catalogue essay to accompany the gallery’s forthcoming exhibition, ‘Harald Sohlberg: Painting Norway’ (13 February to 2 June), whereas Munch chose to foreground the human figure, treating the landscape as an additional expression of ‘a state of the soul’, Sohlberg focused primarily on the landscape, with the merest hint of human presence. This exhibition, which is travelling from the National Gallery in Oslo, marks the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth and will be the first solo exhibition of his work outside of Norway.

Born in Kristiania (modern-day Oslo), Sohlberg was the eighth of twelve children. His father was a fur trader and his mother a farmer’s daughter. He grew up in a small pocket of affluence, which was teetering on becoming a slum. His parents had grand ambitions for their children, wishing for them the education that they themselves had lacked. Sohlberg grew up a competent pianist and strong singer, and began drawing at the age of 14. His father, however, did not deem him talented enough to become an artist, and so he was apprenticed, at the age of 16, to the master scene painter and theatre decorator Wilhelm Krogh. As an apprentice, Sohlberg was obliged to attend classes at the National College of Art and Design, but, dissatisfied, he left after just one semester. Four years later, in 1889, his father gave him permission to break off his apprenticeship without taking his final exams. That summer, Sohlberg travelled alone to the Valdres region to the north-west of Kristiania, taking with him his oils and brushes, and it was here that he made his first significant paintings.

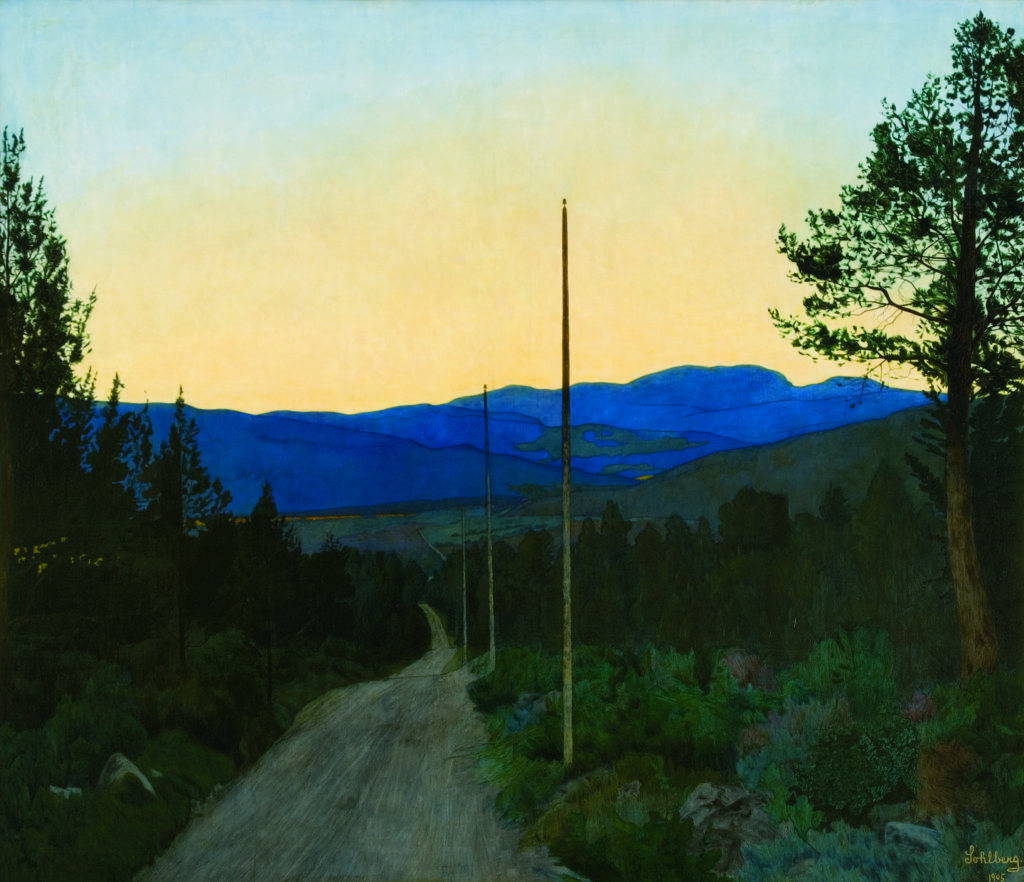

The following summer, Sohlberg painted with Sven Jörgensen at Slagen, and he also spent short periods studying with other Norwegian artists, including Erik Werenskiold, Eilif Peterssen and Harriet Backer. In 1892, he attended Kristian Zahrtmann’s art school in Copenhagen, where he would have encountered the work of painters such as Paul Gauguin, and, following the success of his 1894 painting Night Glow, acquired by the Norwegian National Gallery, he travelled on a scholarship first to Paris and later to Weimar. Despite this time studying abroad, however, Sohlberg remained committed to the landscapes of his native Norway. He visited parts of the country that had not previously attracted artists and helped establish for them an artistic identity. For example, he later lived in the small town of Røros, which was heavily marked by its copper-mining history. While other painters tended to seek out areas of unspoilt landscape, Sohlberg was drawn to this collision of nature and culture and frequently included such elements as roads and telegraph poles in his works – always carefully chosen for their potential symbolic value.

Sohlberg’s early training as a craftsman was to shape his entire career, providing the grounding for what was to become his ‘signature style’. In the course of the 1890s, he replaced his earlier use of free, impasto brushwork with a glazing technique he had learned during his apprenticeship – and which was looked down on by many of his colleagues as unpainterly. Although a modernist in many ways, he also incorporated more traditional and academic methods, such as the use of transfer grids and rulers. Precise drawing was the foundation of all of his work, and this would then be covered by layers of coloured primer, and glazes of transparent paint. It was important to Sohlberg for his pencil-work to remain visible, and he also frequently accentuated his use of a horizontal-vertical grid, not only for its draftsmanly qualities, but for its marking out the symbolic dimensions of the composition, with the horizontal signifying the earthly and the vertical the supernatural or spiritual. Like Munch, he worked with a simplified palette – frequently white, black, blue, red or green – which helped capture something of the specific Nordic light, atmosphere, and mood. He also insisted that each painting must have one ‘dominant’ colour, which he would exaggerate with emotive effect.

“Like Munch, he worked with a simplified palette – frequently white, black, blue, red or green – which helped capture something of the specific Nordic light, atmosphere, and mood. He also insisted that each painting must have one ‘dominant’ colour, which he would exaggerate with emotive effect.”

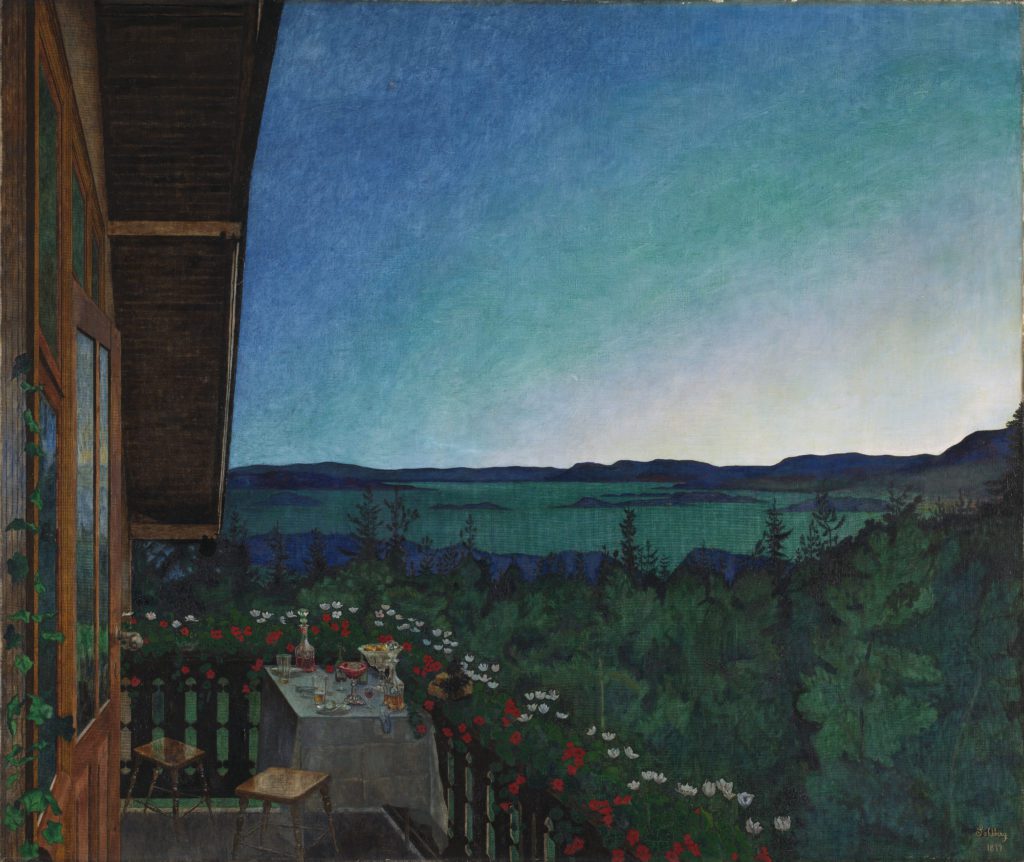

Sohlberg responded to the concrete local landscape around him and collected details from different locations in his sketchbook. Filtered through his emotional responses, these would then be united into one composition. While seeking to honour the Naturalism of his subject, Sohlberg broke with linear perspective and composed his canvases according to strict geometric order. This maintained a certain sense of serenity throughout. The function of line in painting, he said, was to express feelings. He built up space in separate spheres, and his favoured compositional form habitually leads the viewer from a precisely defined foreground to an indefinable and infinite background – as per Winter Night in the Mountains. Another good example, which will also be on show in Dulwich, is Summer Night (1899), painted at the time he became engaged to his future wife, Lilli Hennum. Here, culture – and the implied presence of humankind – is signified by the foregrounded balcony, while the vast fjord beyond references nature. The two worlds are separate but one, with the boundary marked by the flowers on the balcony railing, symbolic of both nature and culture.

Although Sohlberg typically worked on several pictures at once, he never had enough of them ready to comprise a solo show, and so his work was always seen alongside – and thus frequently compared to – that of others. Fisherman’s Cottage (included in this exhibition) was shown at the Venice Biennale in 1907, and he also had works exhibited in the Norwegian Exhibition in Helsinki and the Esposizione Internationale di Roma in 1911; the influential Scandinavian Exhibition that toured to Buffalo, New York, Toledo, Ohio and Chicago in 1912; the International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915; and the Exhibition of Norwegian Art in London in 1928. Frequently representing his country abroad, Sohlberg wrote dismissively in his notebook during the 1890s: ‘Everything has to be so nationalistic, so Norwegian. If you do not have something Norwegian about you, then you are nothing.’ Critics in Norway deemed his ‘unusual’ and ‘original’, but, abroad, he was, for better or worse, almost always considered ‘typically Norwegian’ – apparently for his tendency towards being a freethinker and breaking of rules!

Alongside painting, Sohlberg also wrote poetry and short prose pieces. Some of his more lyrical prose writings describe the moods echoed on his canvases. In all his work, he was concerned with the typical themes of the 1890s: spirituality, faith, eroticism, and death. Alongside Munch, he also made numerous works devoted to the mermaid, a common symbol at the time, used both as a socially acceptable guise for some fairly explicit female nudity, as well as for explorations of the cycle of life and death. In a note about the mermaid theme, Sohlberg wrote that she represents ‘the almighty passion, the meaning of life, upon whom all things depend, that which causes sorrow and happiness, life and death, wealth and destitution, brings life, brings murder, genius and idiots and fills the insane asylums’.

It was in 1899 that Sohlberg first visited the Rondane – which was to become the scenery for Winter Night in the Mountains – on a skiing trip. He moved there, to the mountain wilderness, a year later, and made his first sketches, spending New Year’s Eve of the new century climbing alone under the starry sky. Several studies on show in the exhibition, from his 14 years of working with this scene, will offer insight into his creative process and his efforts to capture the elusive, define the indefinable, and represent the sublime. In a letter dated 1915, Sohlberg wrote: ‘The longer I stood gazing at the scene, the more I seemed to feel what a solitary and pitiful atom I was in an endless universe’. As an older man, he also confessed that his works had ‘by no means been properly understood for the pictorial and spiritual values on which I have been working consistently throughout the years’. Hopefully this is something that will finally be put right with this exhibition and the accompanying, in depth catalogue.

Sohlberg continued painting until his death of spinal cancer in 1935, three months after being awarded a state artist’s income by the Norwegian Parliament.

Top photo: Harald Sohlberg, Winter Night in the Mountains, 1914.

Recommended further reading: