As Henrik Ibsen’s When We Dead Awaken opens in a new co-production from the Norwegian Ibsen Company and the Coronet Theatre, Mark Lawson talks to its Norwegian, British and Irish cast about the dramatist’s enigmatic final play.

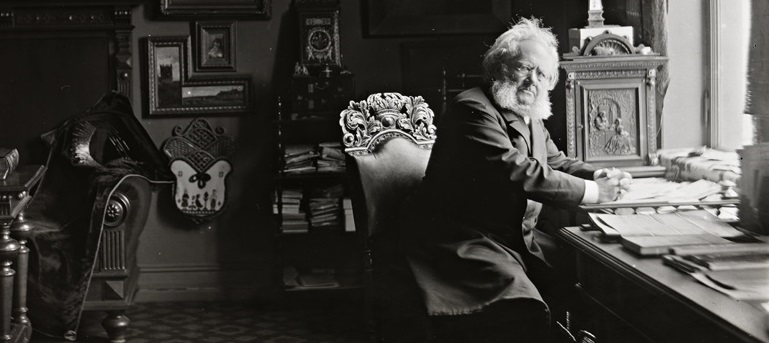

Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) is the second best-known and second most-performed world dramatist (both after Shakespeare). But When We Dead Awaken, which the Norwegian Ibsen Company is now bringing to London’s Coronet Theatre, is unfamiliar even to many of those who know his work.

Actors Øystein Røger and Andrea Bræin Hovig (photo: © Julie Pike)

“It isn’t much known or often done in Norway,” says, one of the cast, Andrea Bræin Hovig, in the Coronet bar after a day of rehearsals. “Friends have said to me: ‘So which Ibsen play is this?’”

A drama that has had a quiet life almost wasn’t born at all. At Christmas 1898, Norwegians were disappointed by the failure to arrive of one eagerly anticipated gift – a new book (in Norway at the time, dramatic texts were published long before performance) by Ibsen.

For the previous two decades, the playwright, like some novelists today, had fallen into the rhythm of a new work every other winter: A Doll’s House, Hedda Gabler, The Wild Duck, and so on. The one variation had been a quickening; Ibsen was so furious at the moralistic rejection of Ghosts in 1881 that An Enemy of the People, featuring a rejected moralist, burned onto the page the following year.

But, after John Gabriel Borkman in 1896, the compositional gap for the first time lengthened, with the biennial sequence lapsing. As 1898 also marked Ibsen’s 70th birthday, there were fears that he had dried up or retired, but, at the opening the following year of a National Theatre in Christiana (now Oslo), Ibsen told William Archer, his British translator and champion, that he was working on the drama that would be called, in Archer’s English version, When We Dead Awaken.

The demand certainly existed. Michael Mayer’s indispensable biography of Ibsen lists the writer’s annual literary earnings. At the end of the 19th century, he earned Norwegian kroner to the equivalent value of £1,931 annually; the Bank Of England inflation calculator equates this to £252,541 today, a sum that very few playwrights could approach, and even then not without TV and movie commissions; all of Ibsen’s income came from publication and performance of plays.

Readers’ and theatregoers’ fears that Ibsen’s career was ending with the century seem to have been shared by the writer. Archer, in an introduction to The Collected Plays Of Henrik Ibsen, reported this account by the dramatist’s friend, Dr Julius Elias: “He wrote When We Dead Awaken with such labour and such passionate agitation, so spasmodically and so feverishly, that those around him were almost alarmed. He must get on with it, he must get on!”

Øystein Røger (Arnold Rubek) with Ragnhild Margrethe Gudbrandsen (Irene von Satow) in When We Dead Awaken at the Coronet (photo: ©Tristram Kenton)

Actor Øystein Røger, who plays the central role of sculptor Arnold Rubek in the new production, says: “I think you can actually feel the urgency within the play – a sense that he had to get it done as quickly as possible.”

“There are big jumps in the action,” adds director Kjetil Bang-Hansen. “He isn’t including linking scenes and details that he would have done in earlier work. He wants to get it finished.”

“[In When We Dead Awaken] he has collected something from almost every earlier play he has written”

Øystein Røger

These instincts from those working on the text 122 years later seem confirmed by another comment from Dr Elias: “His relatives are firmly convinced that he knew quite clearly that this would be his last play, that he was to write no more. And soon the blow fell.”

That was a stroke that started the decline that ended Ibsen’s writing and, in 1906, his life. The feeling that Ibsen was writing against some sensed deadline is increased by the fact that When We Dead Awaken is, as Mayer pointed out, by far his shortest play, the third and final act lasting only quarter of an hour in performance.

The brevity, though, has great depth.

“Ibsen subtitled this a ‘Dramatic Epilogue’,” says Røger, “and he has collected something from almost every earlier play he has written.” In the play, a sculpture becomes a couple’s surrogate “child” in the way that a literary manuscript did in Hedda Gabler; a local “spa baths” nods to An Enemy Of The People; the coastal setting to The Lady From The Sea; trolls and other Nordic folklore to Peer Gynt and Brand, the ending of which high in the mountains is also alluded to in the final play.

Director Kjetil Bang-Hansen (right) in conversation with Øystein Røger (photo: The Coronet)

“It’s a memory box,” says Bang-Hansen. “Ibsen was thinking of what he was leaving behind. We think now it’s because he could see the end coming, and maybe he did, but he had also told people that he hoped to write a new type of drama for the new century, so he was putting away what he had done before. But he never got to write anything else.”

More than a century later, an author who knew that he was dying, the Palestinian American critic Edward Said (1935-2003), wrote a book about artists and writers at the end of their lives. On Late Style, published posthumously in 2004, challenged the common view that, in their final work, creative souls reach technical and intellectual ease and perfection. (The Tempest has often been seen in that way.)

Said argued that some departing artists achieve the opposite of reconciliation. A key example was “Ibsen, whose final works, especially When We Dead Awaken, tear apart his career and reopen questions that are supposed to have been resolved before such works are written. Far from resolution, Ibsen’s last plays suggest an angry and disturbed artist who uses drama as an occasion to stir up more anxiety, tamper irrevocably with the possibility of closure, leave the audience more perplexed and unsettled than before.”

The instinct Said detects is captured in the play’s central metaphor: Rubek has spent four decades on a defining sculpture that, after all that time, he radically changes, almost desecrates, having turned against his early work.

As a final play with a character who can be seen as the dramatist taking his leave of the stage, When We Dead Awaken has an obvious affinity with Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which Prospero, like Rubek, is in exile, wrestling with the possibility of redemption.

“It is very like The Tempest,” says Bang-Hansen.

“Rubek is very similar to Prospero,” agrees Røger; playing this part has made him even keener to take on the Shakespearean role.

William Archer disliked When We Dead Awaken, warning audiences not to rank it among Ibsen’s masterpieces, a remark in part a rebuke to James Joyce, who, perhaps with the contrarianism that was part of the great Irish writer’s nature, had declared it “Ibsen’s greatest play.”

Drawn to modernist experiment, Joyce may have enjoyed the oddness of When We Dead Awaken. The story is a sort of psychological drama, in which Rubek, towards the end of his life, is haunted by, and caught between, Irene, who sat for him as a young model, and Maia, the wife with whom he lives out a dead marriage. In different ways, he has ruined both women.

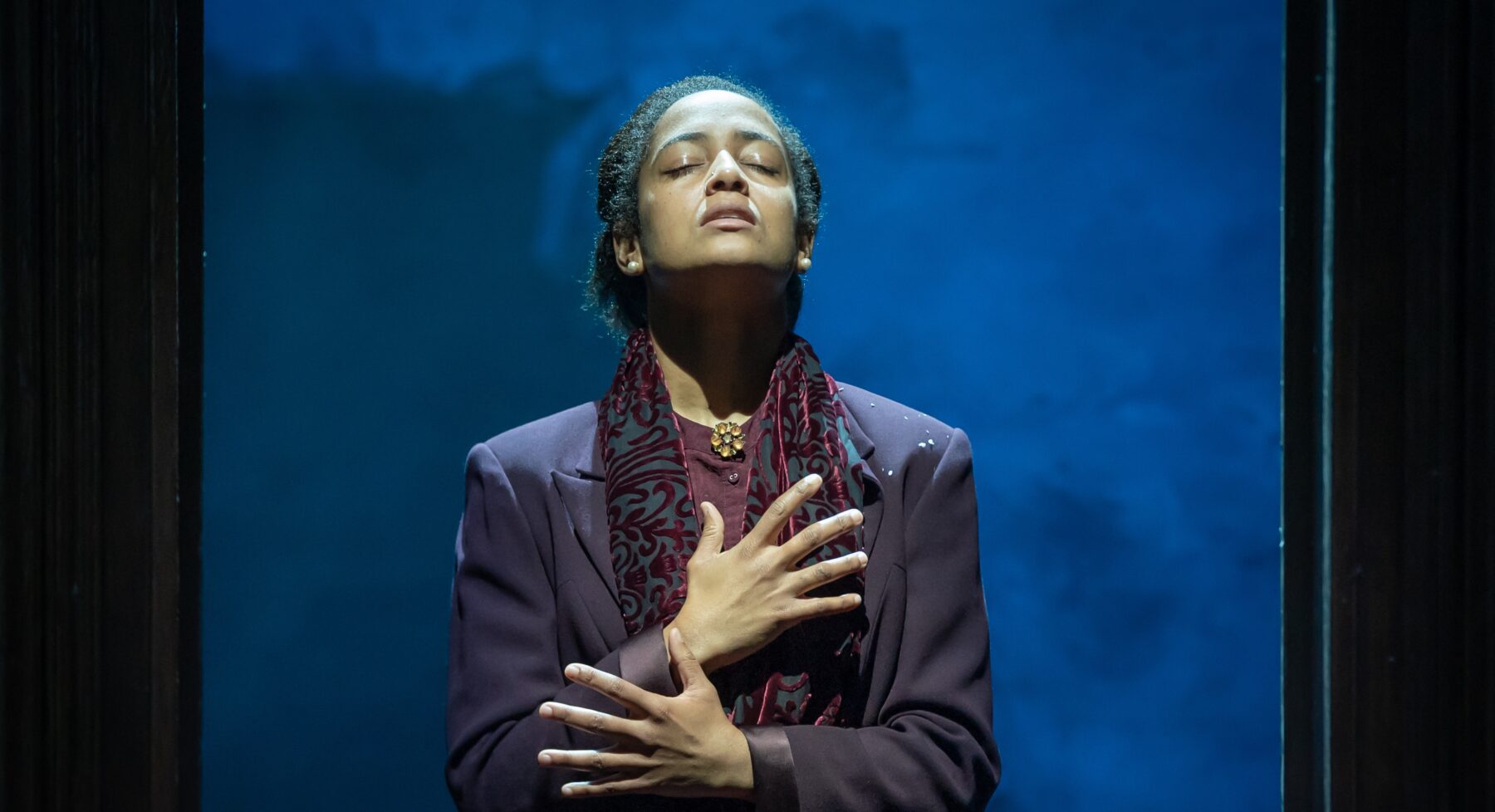

Andrea Bræin Hovig (Maia Rubek) with James Browne (Ulfhejm) in When We Dead Awaken at the Coronet (image: ©Tristram Kenton)

“Arnold thinks that art can be more important than life,” says Røger, “and uses his art to justify destroying the lives of those around him, as Ibsen perhaps did, or feared he had done.”

But this realistic scenario plays out in no recognisable genre, moving between realistic and poetic speech, naturalism and possible supernaturalism. Audiences are left to decide if some – or even all – of the people in the play are still among the living.

Ragnhild Margarethe Gudbrandsen, cast as Irene, says: “We have talked a lot in rehearsal about whether certain characters are actually dead or just spiritually dead. We try to play them as real people but with something broken inside.”

The hidden workings of the mind are crucial to the play, thinks young Irish actor James Browne (the production includes both English-subtitled Norwegian and English). Browne points out that Ibsen was writing When We Dead Awaken at the time Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation Of Dreams. To many a revelation, Freud’s theories would have come as confirmation to a writer as psychologically pioneering as Ibsen.

“The advent of psychoanalysis,” says Browne, “was as big for that society as MRI scans for ours, in terms of showing what’s inside. And it must have been amazing for a writer like Ibsen, who had spent all the time writing what was in his subconscious and suddenly being told why.”

Røger first played Rubek 20 years ago but, now in his late 50s, feels closer to the play’s themes of reckoning and regret: “I think the first time I did it, I played him as a bad guy because he says and does terrible things. But now I’m older and understand him more, I think I defend him more: my job is to find out why he does those terrible things. He’s desperate to live again and make things better.”

When We Dead Awaken runs from 24 February until 2 April at the Coronet Theatre, London

Would you like to stay in touch with Norwegian Arts and receive news of upcoming Norwegian cultural events in the UK? Sign-up for our newsletter.