As a radical new version of Henrik Ibsen’s masterpiece A Doll’s House opens at London’s Young Vic, Sue Prideaux looks back at the play’s origins and explores its enduring message of emancipation.

Ibsen published A Doll’s House exactly 150 years ago. Its success was immediate and sensational. A commentator described it as ‘exploding like a bomb into contemporary life, a play that knew no mercy as it pronounced a death sentence on accepted social ethics.’ Ibsen was hailed as the champion of women’s rights, and A Doll’s House has been seen as the foundational feminist play ever since.

Yet Ibsen always denied writing it as a feminist tract; “I have never written a play to further a social purpose. I have been more of a poet and less of a philosopher than most people seem inclined to believe. I must decline the honour of being said to have worked for the Women’s Rights movement. I am not even very sure what women’s rights are,” he said, as differentiated from human rights in general.

Ibsen knew that a polemic never works on stage. Had he written a straight political piece, it would now be as seldom performed as John Stuart Mill’s On the Subjugation of Women is read. The secret of the play’s timeless relevance and world-wide appeal (every actress wants to play Nora, from Sarah Bernhardt to Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor, to Mao’s wife who played Nora in China – oh, to have seen that!) lies in the fact that the play did not spring from general theorising but from an event in Ibsen’s life that left him racked with personal guilt and a realisation of the collective guilt of patriarchal society.

Ibsen was always susceptible to lively younger women. One such, Laura Petersen, he called his ‘skylark’ – the pet name Torvald calls Nora in the play. Laura married a schoolmaster who subsequently caught tuberculosis. Their doctor advised that the only way to save his life was to travel to a warm climate. Laura secretly took out a bank loan to pay for the trip. When the loan fell due she hoped to raise money by sending Ibsen the manuscript of a novel she had written, asking him to recommend it to his publisher. Ibsen thought it was bad, and refused. In despair she forged a cheque. Discovery followed. Her husband denounced her as a fraud and a liar, unfit to be a wife and mother, and he committed her to a mental asylum.

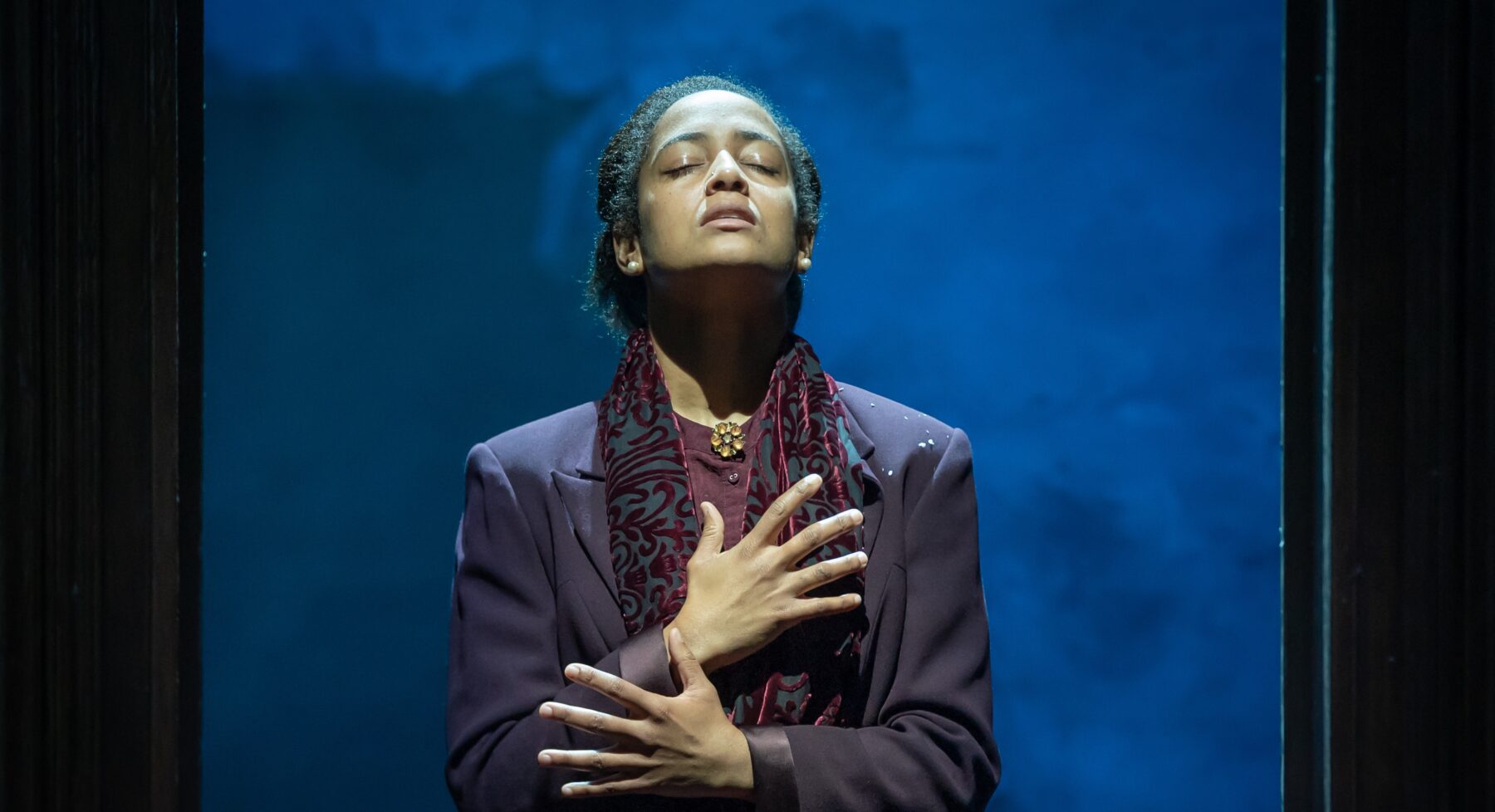

Amaka Okafor, Anna Russell-Martin, Natalie Klamar and Luke Norris in Nora: A Doll’s House (Photo: Marc Brenner)

On hearing of Laura’s committal, Ibsen wrote; “A woman cannot be herself in a modern society with laws made by men with prosecutors and judges who assess female conduct from a male point of view,” and he began A Doll’s House.

The play tells the story of the Helmers, a family on the up. Torvald is about be promoted in the local bank. He completely controls the life of his wife, and the family finances, as all husbands did in 1870, when women were universally denied both education and financial independence, and this was presented to them as a privilege. Torvald calls Nora his skylark, and she plays up to it, acting the pretty songbird in the gilded cage, the sexy spendthrift who gives point to his earning power. But she knows it’s an act. Years earlier, Torvald contracted TB. To save his life, Nora forged a signature to obtain a loan to take him south. When Torvald discovers, he reacts with righteous outrage, denouncing her as a fraud and a liar. Utterly disillusioned, she accuses him of having treated her like a doll and says she’s leaving. Torvald speaks for the whole bewildered patriarchal society when he asks her how she can neglect her most sacred duties:

Nora: What do you call my most sacred duties?

Torvald: Do I have to tell you? Your husband and children.

Nora: I have a duty which is equally sacred.

Torvald: What on earth could that be?

Nora: My duty to myself.

Torvald: First and foremost you are a wife and mother.

Nora: I don’t believe that any more. I believe that first and foremost I am a human being, like you. Or I must try to become one.

We hear the most famous door-slam in history as Nora walks out on her house, her husband and her children.

There are no doors to slam in Nora: A Doll’s House, a new version of the play opening at London’s Young Vic this week. The set features three notably door-less door frames, through which people come and go through time as well as space. Stef Smith’s reimagining of the play follows Ibsen’s plot scrupulously, while using the device of splitting Nora into three so as to examine the feminist plight through fifty year intervals following on from of Ibsen’s play. Nora 3, luminously played by Amaka Okafor, exists in 1918 and voices the seriously-purposed generation who gave their lives to win the vote. Fifty years on, Nora 2 inhabits 1968, arguably the year of maximum female confusion, when abortion became legal, homosexuality decriminalised, and the pill commonplace, and yet Stand by your Man was topping the charts. Natalie Klamar brilliantly realises the utterly muddled moment by using a ridiculously insecure baby-voice and arranging her body into one cliché magazine pose after another. This Nora obviously lives by agony aunt advice on how to be perfect and expects it to work.

The third and final Nora, played by Anna Russell-Martin, exists in 2018, the ♯MeToo moment. She’s scuzzy and she’s harassed and a surreptitious nip from the bottle gets her through the day. She’s married to an Essex-boy banker played with superb insensitivity by Luke Norris who plays the husband to all three Noras. Not an easy brief, but he brings great depth to the continuing timeline of male incomprehension of female needs.

The play ends with each Nora realising she has been treated as a doll and leaving the doll’s house through one of the three empty doorframes. 1918 Nora walks out and lies down in the snow, presumably to die of hypothermia. 1968 Nora heads up the street excited by starting a gay relationship. 2018 Nora ends more ambiguously: as she leaves, she looks back and sees her husband. Maybe he’s coming for revenge, or maybe it’s the start of a proper relationship? The play ends with all three Noras vociferously lamenting feminism’s lack of progress.

The play is cleverly written and acted by a very strong cast. What does it do beyond Ibsen’s original, other than repeat the plot three times? Is the Nora problem still acute in the super-enfranchised British middle-class world where Stef Smith sets her play, and where each of her non-working, well-educated Noras has rights, and a real option of getting a job to pay off the loan?

In 2001, ‘Nora’ was inscribed in the Unesco Memory of the World as ‘a symbol throughout the world for women fighting for liberation and equality.’ It would have been electrifying if Stef Smith had used her authorial freedom to set one of her time-couples outside a Western European democracy, in a place where today’s women are literally giving their lives for exactly those fundamental rights.

Nora: A Doll’s House is at the Young Vic until 21 March 2020

Sue Prideaux’s biographies of Edvard Munch and August Strindberg are available from Yale University Press and her life of Friedrich Nietzsche is published by Faber & Faber