Alongside masterpieces by Edvard Munch and Harald Sohlberg, Norway’s new National Museum presents a miscellany of strange and curious objects, artworks and installations, as Christian House discovers.

This summer’s opening of the new Norwegian National Museum provided a litany of headline-grabbing statistics: the £500 million institution covers some 54,600 square metres, with 90 exhibition rooms displaying a selection of 6,000 works from the museum’s collection of 400,000 objects. This all adds up to a museum that, as its director Karin Hindsbo explains, is set to “last for several centuries.”

Norwegian National Museum in Oslo (courtesy of the museum)

The museum, the largest in the Nordic region, sits on Oslo’s waterfront overlooking the fjord, positioned next to the modernist Radhuset – City Hall – and the Nobel Peace Center, and a short walk from the Astrup Fearnley Museum of contemporary art. It is the latest – and greatest – punctuation in the city’s new cultural quarter.

The Munch Room in the National Museum (photo: Iwan Baan)

The museum’s collection of fine art, design, architecture and costume, reflects thousands of years of creative output in Norway. Of course, some works get more press than others. This, after all, is the location of Edvard Munch’s first version of The Scream. But unusual and memorable things are peppered throughout the collection. Here is our pick of ten marvels to find in the galleries. There are, of course, some 400,000 others.

Sledge by Peder Pedersen Aadnes (circa 1760-80)

Sledge by Peder Pedersen Aadnes, 1760-80 (Photo: Norwegian National Museum/Frode Larsen)

This 18th-century carved and painted wooden pointed sledge was the decorative creation of Peder Pedersen Aadnes. At the age of eighteen, Aadnes was engaged to complete the decoration of Fluberg Church in Søndre Land, north of Kristiania (Oslo). His considerable talent soon attracts new commissions. After an apprenticeship to an art painter in Kristiania, he matures into a skilled artist and decorator. The market for Norwegian craftsmen is small. Aadnes was immensely versatile, undertaking decorative projects in churches and private homes, painting portraits, as well as decorating furniture and other household items.

A Waterspout on the Bay of Naples by Thomas Fearnley (1833)

Thomas Fearnley, A Waterspout on the Bay of Naples, 1833 (Photo: Norwegian National Museum/Børre Høstland)

Thomas Fearnley – one of the most celebrated Norwegian landscape painters of the 19th century – was particularly interested in weather phenomena. In the Bay of Naples, Italy, on 8 July 1833, he observed a waterspout, and captured it in this oil study. The quick sketch pictures the spinning vortex stretching down from the underside of the dark cloud to the surface of the water.

Bendik and Aarolilja by Bendik Riis (1955)

Bendik Riis, Bendik and Aarolilja, 1955 (Photo: The National Museum/Børre Høstland)

In the classic Nordic ballad, Bendik and Årolilja, two lovers die for their forbidden love. In this painting, Bendik Riis casts himself as his namesake in the poem. For much of his life, Riis was an outsider and he suffered long periods of mental illness. Many of his works are critical of society, based on his personal experience, while others suggest rose-tinted fantasies.

Measuring the Depth of Snow by Oddvar I. N. Daren (1981/2016)

Oddvar I . N. Daren, Measuring the Depth of Snow, 1981/2016 (Photo: Norwegian National Museum/Oddvar I . N. Daren/BONO)In a series of eight photographs, Oddvar I. N. Daren’s body is ‘knocked’ into the ground one foot at a time, as if by an invisible force. The use of the body as a unit of measurement seems amusing and a little absurd. But Daren’s gesture reminds us that, historically, units of measurement were almost always based on the human body. A committed environmentalist, Daren took part in the most heated environmental conflict of the 1970s, against the development of the Alta River in Finnmark. Even so, his works are rarely overtly political. Instead, he explores how art and nature can meet without being trivialised.

The Henrik Bull Room (1897)

The Henrik Bull Room installed in The Norwegian National Museum (Photo: Norwegian National Museum/Ina Wesenberg)

In 1897, the Kristiania Crafts and Industry Association commissioned Henrik Bull to design an interior for the Stockholm Exposition. By engaging architects, the association aimed to improve the quality of Norwegian furniture production. Bull’s task was to “translate the Old Norse style into contemporary furniture”. Subsequently, the interior attracted great interest at the 1900 Paris Exposition, after which it was installed in the new building of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Kristiania (Oslo).

Centrepiece by Torolf Prytz (1900)

Centrepiece designed by Torolf Prytz, manufactured by J. Tostrup, 1900 (Photo: Norwegian National Museum/Frode Larsen)

Torolf Prytz was something of a renaissance man of the early 20th century: an architect, designer, goldsmith and politician, Prytz divided his time between running J. Tostrup, his family firm of goldsmiths, and his duties as a government minister and the president of the Norwegian Red Cross. This silver centrepiece, with its dragestil – Norwegian dragon style – flourishes was manufactured by his company and exemplifies Prytz’s reputation for designing fine filigree silver.

Communication Piece by Hilmar Fredriksen (1972)

Hilmar Fredriksen, Communication Piece, 1979 (Photo: Norwegian National Museum/Hilmar Fredriksen/BONO)

Hilmar Fredriksen explained that Communication Piece was “about mutual dependence between two persons: the introvert and the extrovert. The introvert sits inside the carriage without being able to move; he looks out through a slit, seeing but unable to act. The extrovert enjoys full mobility, but wears opaque glasses that reflect the surroundings.” The design of the work is simple and ascetic. Likewise, the choice of material for the body of the carriage – plywood – expresses simplicity. Halfway between a box and an ancient Egyptian mummy coffin, Fredriksen’s carriage shares a formal kinship with early Modernist painting.

Maren dress, Ingeborg hat, Emily shoes by Edda Gimnes (2017)

Edda Gimnes: Maren dress, Ingeborg hat, Emily Shoes (SS2017), 2017 (Photo: The National Museum/Frode Larsen)

What is a perfect look? Well, Norwegian fashion designer Edda Gimnes finds perfection boring. And so, although right-handed, she draws her designs with her left hand. Many of her outfits are developed from small, naïve sketches, which she enlarges, prints on cotton, and transforms into wearable garments. Her dresses, hats, bags and shoes are patterned with colourful scribbles in a flat, two-dimensional idiom. In 2016, a year before she designed this outfit, The New York Times marked her as one of ten “fresh out of fashion school designers to watch”.

Ho-Ho-Ho by Berit Soot Kløvig (1969-70)

Berit Soot Kløvig, Ho-Ho-Ho, 1969-70 (Photo: Norwegian National Museum)

The title of Berit Soot Kløvig’s work is based on the formula for heavy water, D2O. The piece can be seen as an expression of Cold War anxiety, but also as a contribution to the debate about the construction of nuclear power plants in Norway. The artist started work on Ho-Ho-Ho in the same year that the Norwegian Parliament launched a feasibility study into the use of nuclear power. The plans were never realised. Despite the underlying seriousness, the giant molecule-like formation – created out of frying pans, eggs and geometric painting – also has a playful, humorous aspect.

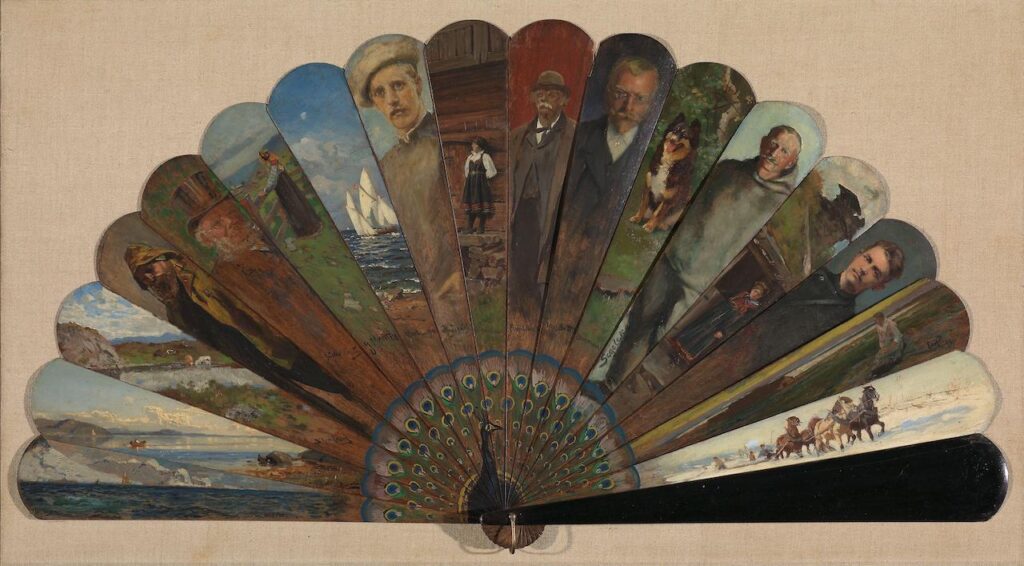

The Artist Fan, 1898

The Artist Fan decorated by Hans Heyerdahl, Thorolf Holmboe, Fredrik Kolstø, Otto Sinding, Gustav Lærum, Gerhard Munthe, Hans Gude, Jacob Bratland, Axel Ender, Asta Nørregaard

Eilif Peterssen, Elisabeth Sinding, Karl Uchermann, Severin Segelcke, Christian Skredsvig, Amaldus Nielsen, Carl Fredrik Sundt-Hansen and Christian Krohg (Photo: Norwegian National Museum)

This fan was given to the painter and teacher Knud Bergslien by friends and former students from his school of painting in Kristiania (Oslo) at an anniversary party in 1898. Each picture on the fan’s blades is signed by one of the eighteen artists, including major figures such as Gerhard Munthe and Christian Krohg. Some of the images show prominent men of art and science and Bergslien himself is depicted in the middle sporting a white moustache.

Norwegian Arts would like to thank Simen Joachim Helsvig at the Norwegian National Museum for his help in compiling this article.

For more information on these other works in the collection visit: Norwegian National Museum

Interested in staying in touch with Norwegian Arts and receiving news of upcoming Norwegian cultural highlights in the UK? Sign-up for our newsletter.

Top photo: Interior of the Nasjonalmuseet (Photographer: Annar Bjorgli)