As a new Royal Academy exhibition brings together works by Edvard Munch and Tracey Emin, Munch’s biographer Sue Prideaux explores the corresponding struggles and divergent expressions of two tortured masters separated by a century.

Tracey Emin loves Edvard Munch. They were born exactly a century apart: Emin in 1963, Munch in 1863, but she calls him “my man Munch”, like a boyfriend. She first saw Munch’s pictures in a book, before she went to art school, aged about 17. Immediately she knew, “That’s my art. That’s me. That’s my world.” It was the start of a lifetime obsession. At art school she made thousands of woodcuts inspired by him. She titled her leaving dissertation My Man Munch, and she has not deviated from her devotion ever since. When she first encountered the Scream, she saw another lost soul like herself, and wanted to jump inside it and cradle it in her arms. In 1998 she travelled to Munch’s studio in Aasgardstrand to make a video of herself naked and screaming. Now, aged 57, she is realising a lifetime’s ambition exhibiting alongside her hero. The exhibition was intended to inaugurate Oslo’s newly relocated Munch Museet, but Covid and construction challenges intervened and it is now showing first at London’s Royal Academy. When the new museum opens, Oslo will see an expanded version of the show.

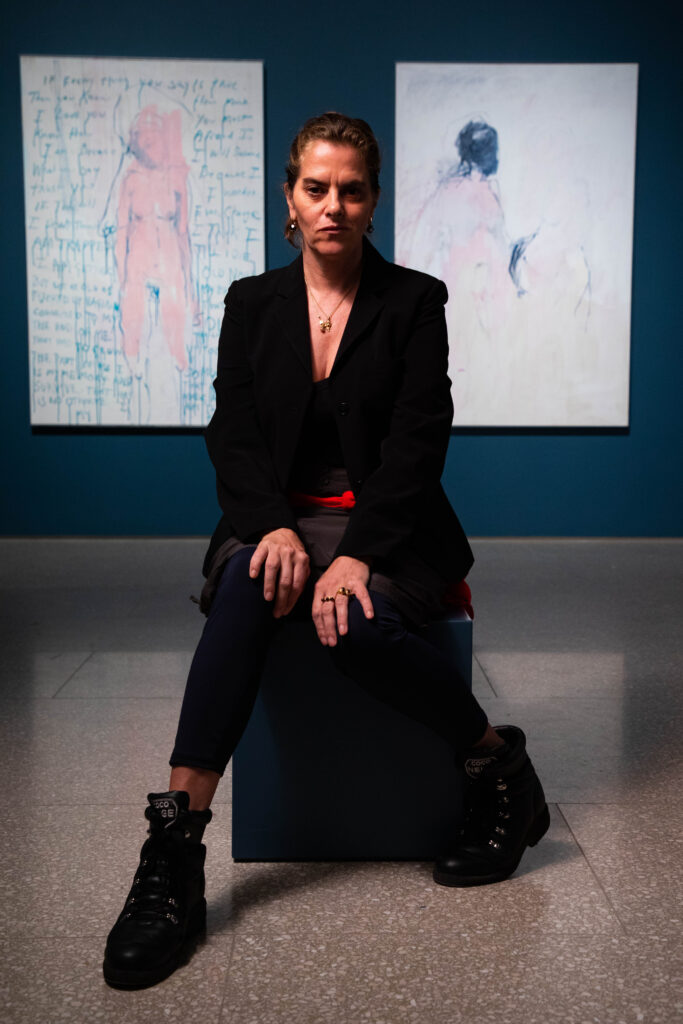

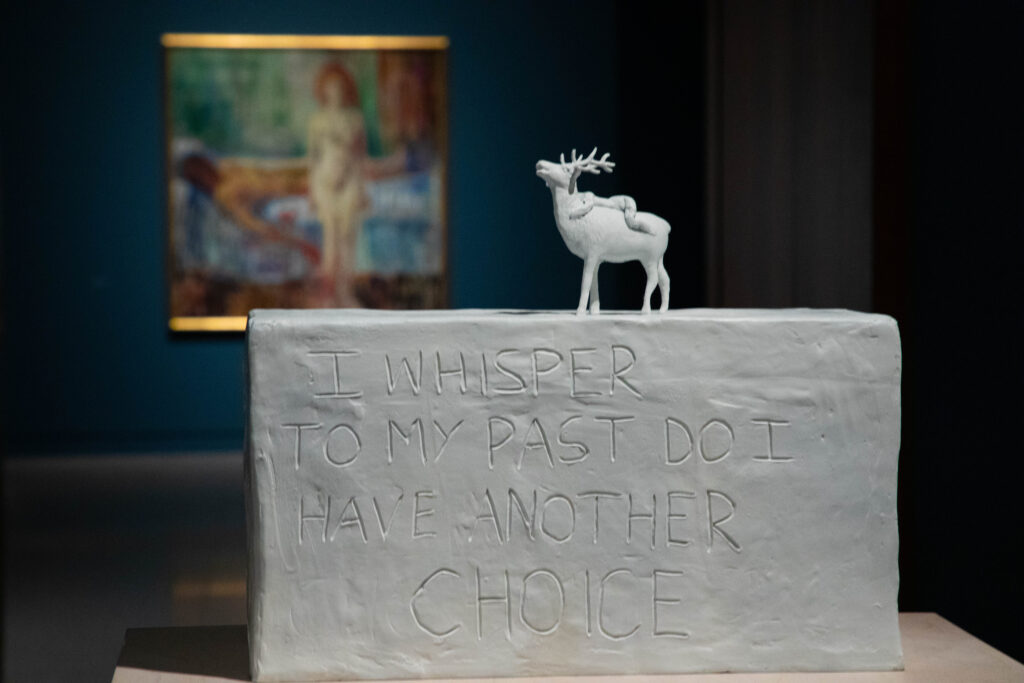

Gallery view of Tracey Emin / Edvard Munch

The Loneliness of the Soul at the Royal Academy of Arts.

Photo: © David Parry/ Royal Academy of Arts

The Loneliness of the Soul draws you deep into the harrowing inner spiritual loneliness of both artists. Both feel profoundly isolated from society by the tragedies they experienced in their lives. Both take these very personal traumas as the central subject matter of their art. First-hand experience is, they believe, the raw material for understanding the human condition. The only base for truthful art, is life. Munch was born into a family with a history of insanity. He suffered all his life from anxiety that he would go mad (he never did), his mother died when he was five, his favourite sister ten years later, his brother probably committed suicide; another sister, probably schizophrenic, was shut up in an asylum. Highly sexed, known as the handsomest man in Norway, Munch’s love affairs were disastrous; one ending in a shooting. Emin was the child of an improvident father. She was raped at thirteen, gave up on school to go vagabonding around as a wild child, suffered sexual abuse, endured two horrible abortions, and has never found the love that she still craves. At times their pictures are so searingly honest that we feel guilty and voyeuristic just looking at them.

Both artists have been extremely controversial for the same reason: their art lies in autobiographical self-confession. Grief, longing, loneliness, sexual anguish, ageing, childlessness, existential despair: all the emotions that frighten us pour out onto their canvases, leaving the viewer to cope as best they can with the psychic shock. Like horror films zooming into our brains, they deliberately show us our own most terrifying possibilities. Munch’s Scream, one of the most famous images in art, created a huge scandal when it was first shown.Emin’s My Bed, a squalid unmade bed strewn with used condoms, tampons, a toy dog, a pregnancy test, pills and vodka, created an equal scandal in 1998. Society reacted with shock to both. In Oslo, a public debate was held on the subject of whether Munch was insane. Emin was accused of über-narcissism, even in an age obsessed with selfies, reality TV shows and celebrity gossip. Both suffered dreadfully from the public insults, but neither gave up on exposing their emotional truth, whatever the personal cost.

Both often refer to the soul. Munch speaks about making “soul art, not soap art”, and about portraying “the ghost that arises from the deep cellar of my soul”. Emin puts it this way: “I start with myself, and I end up with the universe.”

Both see a deep religious significance in art. Shortly after the death of his father, Munch expressed his powerful vision of the spiritual capacity of his work in his St Cloud Manifesto: “There should be no more pictures of men reading and women knitting” (this was a dig at his contemporaries, the Impressionists), “I will paint people who live and breathe and suffer and love… People will understand the sanctity and power of it and will take off their hats as if in church.” A similar mystical revelation occurred to Emin in 1993, on a beach in Margate. Suddenly she felt she was part of “Something – Something a Million Billion times bigger than me.” She stooped to write in the sand; “I need art like I need God.” She has lived by that credo ever since.

Tracey Emin, You Kept it Coming, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 152.3 x 152.3 x 3.5 cm. The artist & Xavier Hufkens, Brussels © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

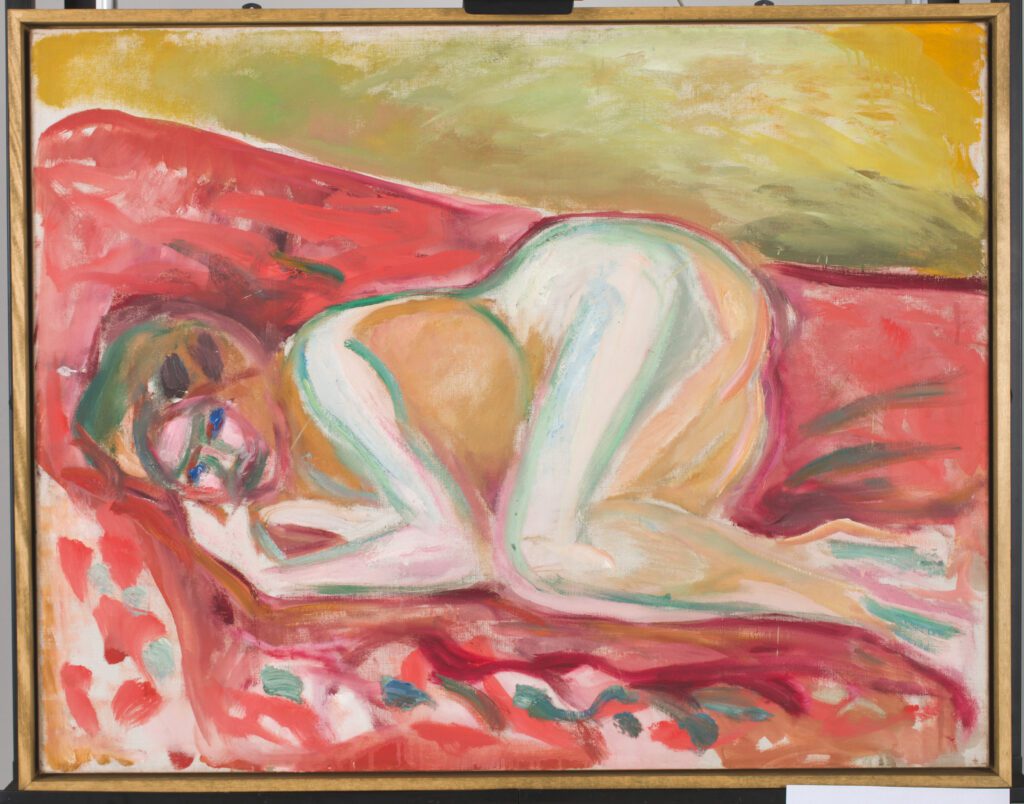

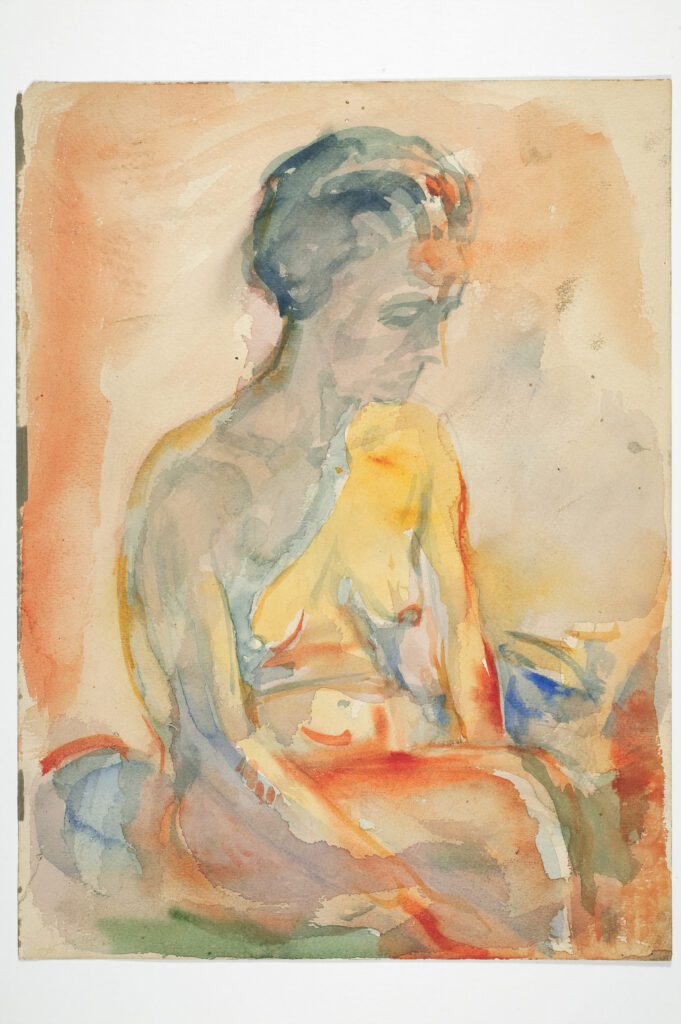

The Loneliness of the Soul has been three years in the making. It started in 2017, with Emin trawling the sprawling archives of the Munch Museum to choose the works that resonate most powerfully with her own work. She was drawn to the extraordinary understanding of the female psyche that suffuses Munch’s female nudes. “I looked through 800 paintings, 2,000 watercolours, thousands of graphic works. Given a completely free choice, I went for loneliness, vulnerability and the fragility of the emotions.” She chose 19 oils and watercolours. They hang alongside 25 of her own works: paintings, neons and sculptures, some displayed for the first time.

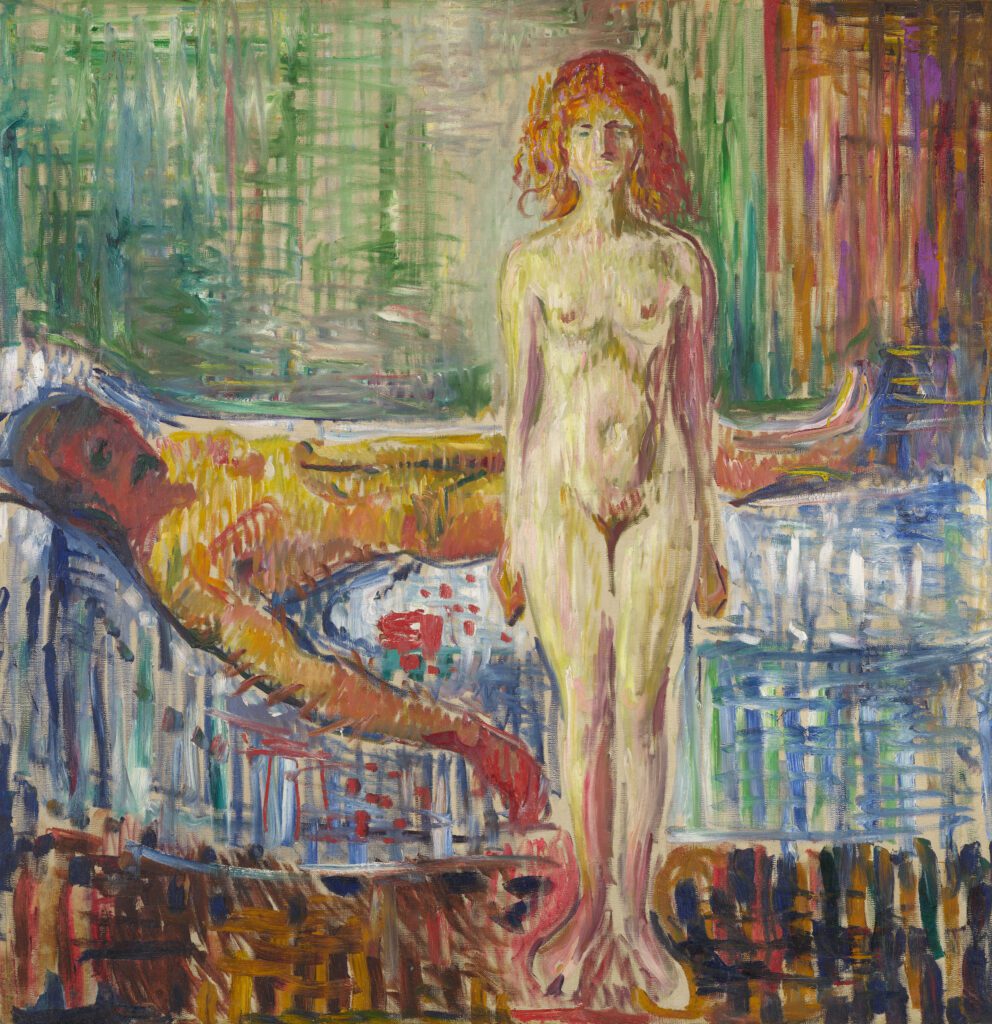

It is a show almost exclusively of female nudes. Munch is famous for mirroring our existential angst through images of the ‘other’ (think Scream). He expresses the anguish of the world through a wide repertoire: landscapes, street life, pictures of children, portraits, many self-portraits; but here we are shown only his female nudes, although in Consolation (1907) and The Death of Marat (1907) his own nude figure stands in relation to the female. Emin’s only subject matter is herself. You will never see a physical setting, another figure in relation to herself, or a male nude. She never paints a figure who is not herself because; “Everything comes from inside me.”

Emin exists in a more upfront age than Munch. He gently presents his own traumas. The ghosts that live in his deep cellar rely heavily on suggestion, symbolism, and emotional use of colour. Emin shows no such tact. Her colours are black and blood-red. Black is used for sparse, thorny outlines. Blood-red for explosive flurries, clots and drips of emotional narrative. Occasionally there are areas of rather sickly pink for flesh. Technically, she is heavily influenced by Munch. She adopts his (then revolutionary) expressionist technique of allowing the paint to run and dribble down the canvas, heightening the impression of hectic anxiety by implying that the paints, like the emotions, are out of control. She also follows Munch’s innovation of leaving areas of canvas completely unpainted, giving the impression that the picture was created and finished in the heat of one intensely emotional moment. This is neither true of Munch’s pictures or of Emin’s, but it’s a terrific artistic device.

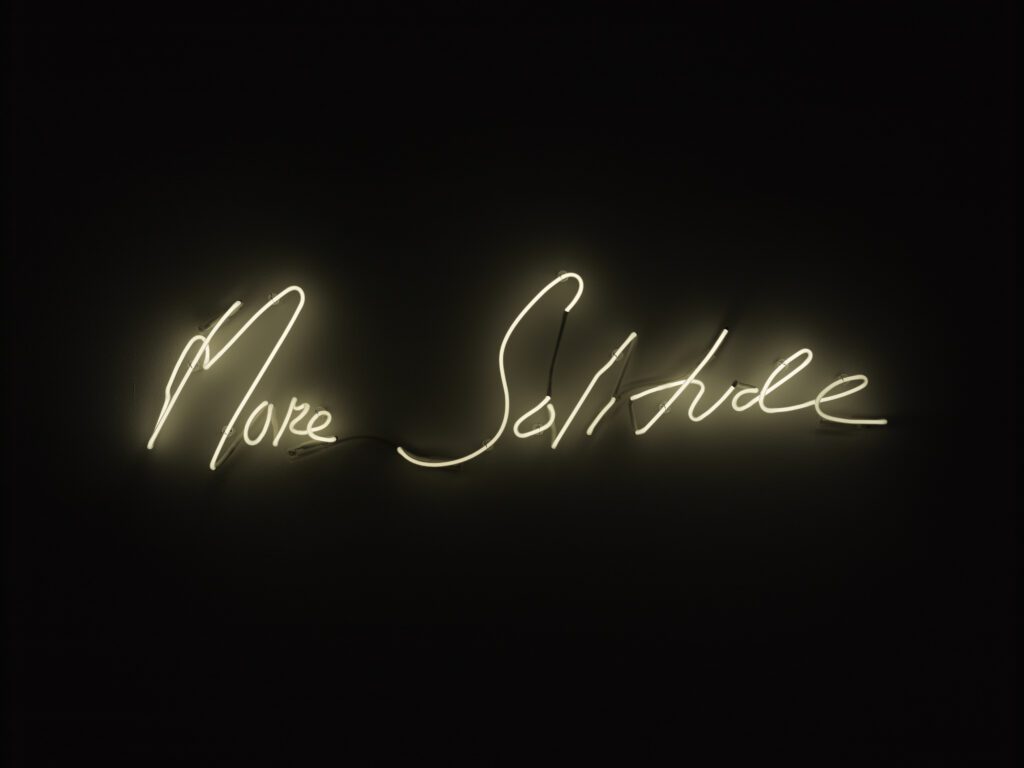

It’s a shocking show. Emin’s canvases are big, mostly a couple of metres each way. They are all nudes of herself, mostly splay legged, sometimes on all fours. You enter to a vast in-your-face canvas entitled ‘Ruined,’ looking straight up her legs to her bleeding vagina. One wall is lit by the words ‘My cunt is wet with fear’ written in tubular neon.

Tracey Emin, More Solitude, 2014. Neon, Edition 2/10, 30.6 x 115 cm. Collection of Michelle Kennedy and Richard Tyler © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

Frankness has progressed a long way over the hundred years between Munch and Emin. Every generation wonders whether it has reached the limit. It’s an interesting historical question to ponder as you go round the show. How inoculated are we against shock? How effective is the confrontational compared to the power of suggestion? Another thing I wondered as I looked at her pictures was just how the subject matter of Emin’s art will develop? Earlier this year, she was diagnosed with a fast-spreading cancer. She is recovering now. But her reproductive organs that have formed such an important part of her self-identity and that loom so large in the iconography of her art, have been removed, and her vagina has been altered by surgery.

Fortunately, the prognosis is good. It looks as if Emin, the survivor of so many ghastly experiences, will chronicle her future existence within her drastically changed and wounded body, through an ever-deepening comprehension of the role of art. This will surely be achieved, to quote her own words; “With Munch… Always with Munch… Never leaving Munch.”

Tracey Emin / Edvard Munch: The Loneliness of the Soul is at the Royal Academy, London, until 28 February 2021

Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream by Sue Prideaux is published by Yale University Press