In the mid-20th century, on the west coast of Norway, Hannah Ryggen used her loom to create feminist and anti-fascist artworks out of spools of thread. As a new book is published on the artist’s work, Katie Treggiden investigates her enduring legacy and discovers how Ryggen has inspired a new generation of textile artists.

“During the Renaissance […] the once prized art of needlework was relegated to the status of mere craft.” So opens a new book by Charlotte Vannier entitled Threads: Contemporary Embroidered Art which seeks to rectify this relegation by celebrating the work of more than 80 artists for whom the needle is mightier than the brush. But the hierarchy that places art above craft, and in doing so the labour of men above ‘women’s work’, has a long history – one that Richard Sennett, author of The Craftsman, traces back to Aristotle, quoting The Metaphysics:

“We consider that the architects in every profession are more estimable and know more and are wiser than the artisans, because they know the reasons of the things which are done.”

As well as placing thinking above making, Aristotle uses the Greek word cheirotechnon or ‘handworker’ for artisan in place of the older word demioergos, which combined ‘public’ and ‘productive,’ placing craft at the heart of industrious communities. Craft was already becoming domesticated, and by extension feminised, in ancient Greece. Vannier suggests that it was in the 1960s and 1970s that female artists took up needlework and “asserted their status as artists in their own right”, but women have been using needles to subvert the restrictions placed upon them for far longer. In eighteenth and nineteenth-century Japan, peasants were restricted to wearing bast and hemp, fabrics with such a loose weave that they wore easily and let in the cold. Sashiko stitching emerged as a way to fill the gaps and strengthen and insulate the fabric, and women in the Nambu region developed highly decorative koginzashi and hishizashi stitches to subvert these punitive sumptuary laws.

In the early 20th century, suffragettes countered arguments that only ‘unwomanly women’ wanted the vote by creating protest banners and handkerchiefs using highly accomplished, and defiantly feminine, needlework. And in 1923, just as Anni Albers (1899–1994) was subverting Walter Gropius’ expectations of the ‘beautiful sex’ at the Bauhaus in Germany, Swedish-Norwegian artist Hannah Ryggen (1894–1970) put down her paintbrush to take up weaving. Despite recognising the industriousness and perseverance required for her chosen medium, her fiancé’s response was typical of its time:

‘Weaving is women’s work from time immemorial, and […] it seems only natural that you who are such a true woman, decided to weave rather than paint art. Painting is in a way more men’s work.’

Undeterred, she set about creating a body of work that not only fused folk art traditions with contemporary art, but was also a damning critique of social inequality, injustices at home and abroad and the rising fascism of the time. Proclaimed a genius by (male) art critics and exhibited all over the world, she has since been written out of Norwegian art history and is only now being rediscovered. In 2017–2018 Modern Art Oxford mounted Hannah Ryggen: Woven Histories, an exhibition exploring Ryggen’s “intense relationship to the world around her” and her “impassioned responses to the socio-political events of her time”. And in September 2019, Hannah Ryggen: Woven Manifestos opened at The Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Germany, featuring 25 of her tapestries, described by the Schirn as “spectacular visual attacks”. With 122 illustrations, Marit Paasche’s new book, Hannah Ryggen: Threads of Defiance seeks to reinsert Ryggen into art history where she belongs; but perhaps more importantly, it repositions craft as a powerful tool in its own right.

Ryggen’s tapestries can indeed be seen as art but, perhaps more accurately, also as activism. Fishing in a Sea of Debt (1933) depicts debt collectors “fishing in the bloody waters of financial ruin” and doesn’t pull its punches – a woman’s body sinks to the bottom as a man struggles to keep the heads of two small children above water and a doctor takes coins from a dead man on the shore. Ryggen herself wrote a poem to describe Mother’s Heart (1947), which includes the lines “something happens to the child/ the heart is broken into a thousand/ pieces. She crawls around/ to collect the shards/ People watch helplessly.” Other tapestries protest against the war between Italy and Ethiopia (Ethiopia, 1935), the treatment of Carl von Ossietzky – the German pacifist who received the Nobel Peace Prize – at the hands of the Third Reich (Death of Dreams, 1936) and the North Atlantic Treaty (Jul Kvale, 1956).

Hannah Ryggen, Grini, 1945, Tapestry weave in wool and linen, 191,5 x 168,5 cm, © Trondheim Kunstmuseum, Norway, VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2019.

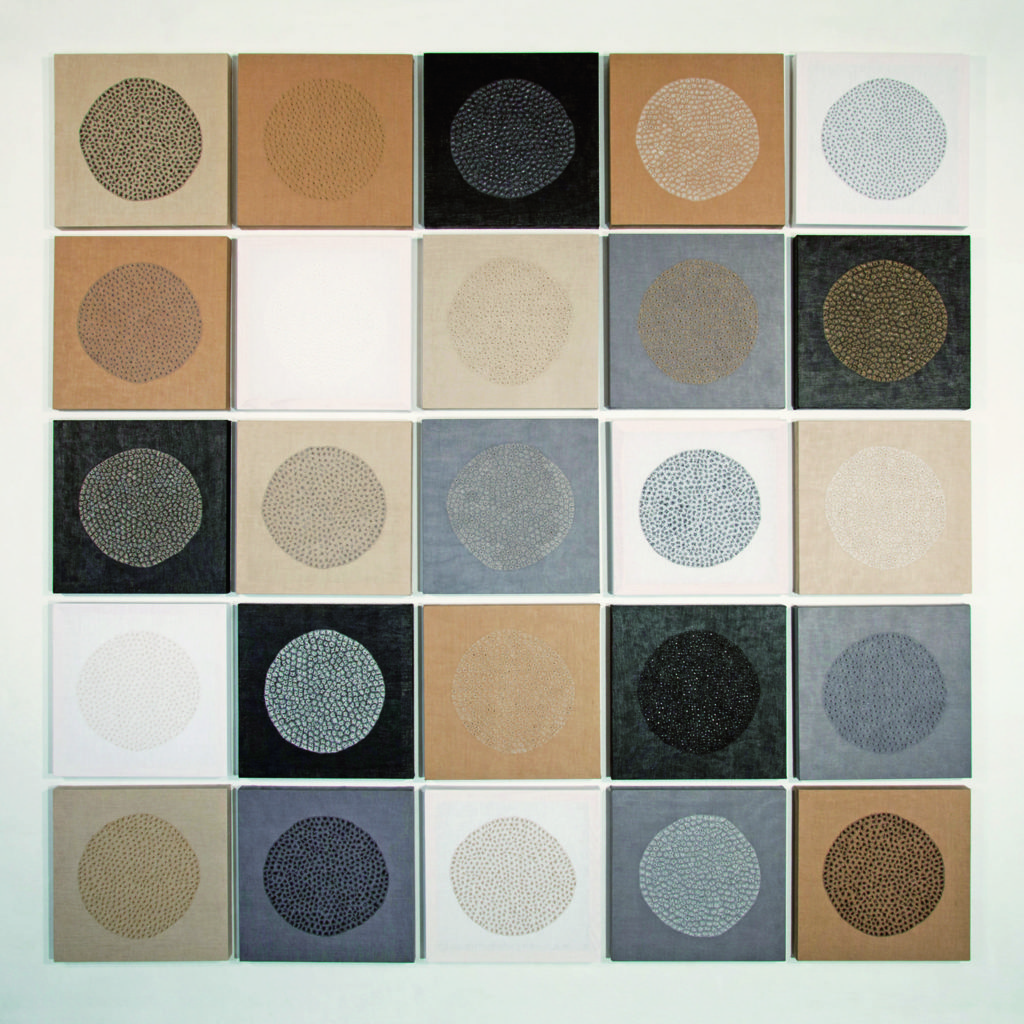

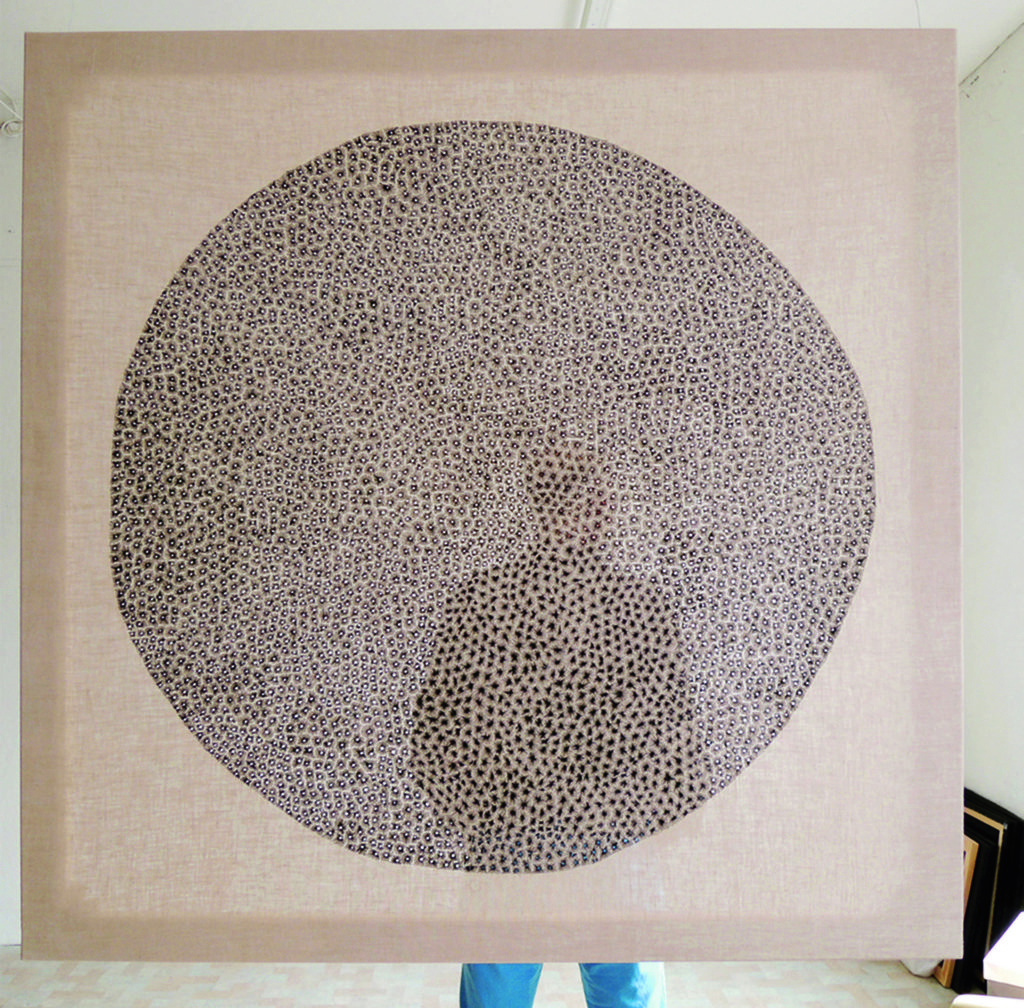

Ryggen inspired a generation of Norwegian women to express their own defiance through thread. One of the artists profiled in Threads: Contemporary Embroidered Art is Äsa Ljones. Her grandmother taught her hardangersaum, a type of needlework unique to the rural area on the west coast of Norway where she grew up. Her early work at the Bergen Art Academy involved stitching together locally sourced fish skins into large two- and three-dimensional forms and embroidering natural rubber with silk. Today, she still honours her ancestry and humble origins in the large-scale embroidered wall hangings which no hang in many of Norway’s largest museums and the Norwegian Embassy in Nepal’s Kathmandu. She uses the primhol (‘prime hole’) technique particular to hardangersaum to create semi-transparent pieces which play with natural light to create a subtle, meditative quality. “I am looking for a silence that evokes something in the user,” she tells Vannier.

Norwegian Sweater by the British artist Celia Pym is also featured in the book. When Norwegian textile designer Annemor Sundbø bought Torridal Tweed og Ulldynefabrikk, Norway’s last shoddy mill – which produces yarn from refuse textiles – she also acquired 16 tonnes of cast-off woollen sweaters, socks, mittens and underwear, that ranged from 30 to 100 years old. They were all destined to be shredded for ‘shoddy’ (recycled yarn). However, realising the value of their record of ordinary working people’s skills, she kept some of them and passed one on to Pym, who is known for darning other people’s clothes. “It’s the most badly damaged object I have ever had to mend,” Pym tells Vannier, “and also the first sweater that I have mended without knowing how the damage occurred.” Inspired by her grandfather’s old darned jumper, Pym is interested in the patterns of use that damaged clothes reveal and how mending clothes often equates to caring for those who wear them.

Norwegian Sweater, original damaged sweater from Annemor Sundbø’s Ragpile collection, with white wool darning by Celia Pym, 2010

While the defiance expressed by Pym, Sundbø and Ljones might be quieter than Ryggen’s, one contemporary artist is following more closely in her footsteps. Featured in another new book, Vitamin T: Threads & Textiles in Contemporary Art, Britta Marakatt-Labba was raised in a Sámi community in Sweden and went on to study in Norway. She created The Roots (2018) in response to the attacks in Norway in 2011 by the right-wing extremist Anders Behring Breivik, in which several young Sámi people lost their lives. Six trees, their roots severed, represent their lives cut short, and twelve figures their mourning mothers. Breivik not only shot 69 people on the island of Utøya that day, but also detonated a bomb in the centre of Oslo that killed eight and injured many more. The blast also tore through Hannah Ryggen’s We Are Living on a Star (1958) which was on view in the entrance hall of the High Rise, a government building in Oslo.

Hannah Ryggen’s We Are Living on a Star (1958) on view in Frankfurt (© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2019, Photo: Norbert Miguletz)

One of her more optimistic pieces – a woven scene of a naked couple in the womb of mother earth – it took on new significance when it was restored and returned to its rightful place in the High Rise, next to a plaque that states, “The mysteries of the universe and love’s essential place in our world.” Its faith in love as a personal and political force endures in spite of everything, a pretty powerful message for “mere craft”.

Threads: Contemporary Embroidered Art by Charlotte Vannier is published by Thames & Hudson

Hannah Ryggen: Threads of Defiance by Marit Paasche is published by Thames & Hudson

Vitamin T: Threads & Textiles in Contemporary Art is published by Phaidon

Hannah Ryggen: Woven Manifesto is at Frankfurt Schirn until 12 January 2020

Top photo: Hannah Ryggen: Woven Manifestos on view at The Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (Photo: Norbert Miguletz)