Per Olaf Fjeld is a Norwegian architect, professor and a former student of Louis Kahn, the American monumental architect, who he writes about engagingly in the book Louis I. Kahn – The Nordic Latitudes (co-authored with his artist wife, Emily Randall Fjeld). On 10 June, Fjeld will be discussing Kahn at the London Festival of Architecture.

Fjeld’s book explores Kahn’s relationship with the Nordic countries and Nordic architecture in general, an aspect of the US architect’s oeuvre that remains lesser known despite Kahn being born on the Estonian island of Saaremaa. He lived there for the first five years of his life and later maintained relationships with a number of leading Nordic and European architects.

The Fisher House in Pennsylvania, designed by Louis Kahn in 1967. Fjeld says: “This particular house has been important for many architects, including myself, due to its complex plan- how one room directly connects to another.” (Photo: Per Olaf Fjeld)

After taking part in Kahn’s famous University of Pennsylvania Masterclass, Fjeld went on to work and teach with Norwegian architect Sverre Fehn and later set up his own practice. His most recent book is a collection of six lectures he gave at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts’ School of Architecture called The Power Of Circumstance – Architecture And Creative Independence. The title is inspired by the famous Kahn quote: ‘How accidental our existences are, really, and how full of influence by circumstance’.

On the eve of the London festival, Fjeld talked to Norwegian Arts about the role of teaching, keeping an open mind and eureka moments.

Why did you want to write this book about Kahn’s relationship with the Nordic countries?

Because I realised more and more that he had a clear connection to the North. Not only due to the fact that it was his birthplace, but also in relation to his architecture in general. I think it’s very much based on the strong relationship between the material and the capacity of the material to take on light. This relationship between material, structure and light is a key aspect of Nordic architecture.

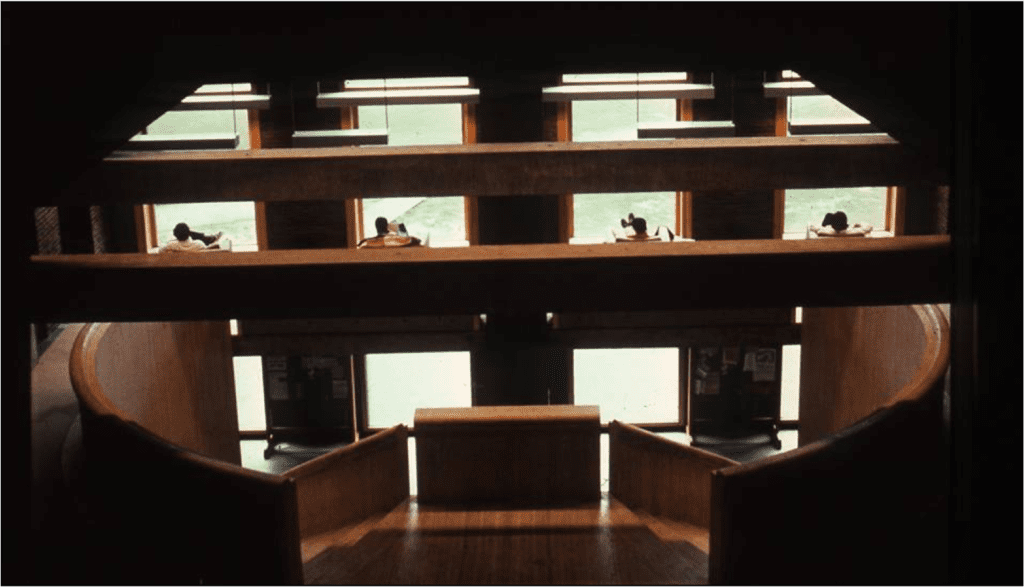

Phillips Exeter Academy library, designed by Louis Kahn (1965-72), featuring the relationship between material, structure and light. (Per Olaf Fjeld)

What are the main features of Nordic architecture in your view?

It has something to do with the relationship to nature. You couldn’t survive in the North without having a clear respect for nature. You have to understand the direction of the wind, the sun, where the snow is blowing. This relationship to the light, to north, south, east and west, is a key issue in Scandinavian or Nordic architecture. At the same time, you have to pick materials that have the capacity to withstand the forces of nature. In a way it was, and still is, based on survival.

Fishing village, Lofoten, Norway. An example of architecture for the elements. (Photo: Per Olaf Fjeld)

But there is also a social consciousness, an understanding that you are not alone in the world but part of a community. All of this is part of what Kahn would have sensed when he went back to Saaremaa as an adult in 1928. That reading of nature as a place, in which architecture has to perform, is still very much part of Nordic architectural thinking.

Why do you think there is so little research on Kahn’s relationship with the North?

I think because the US education system and architectural world was not so interested in pursuing his past. And that it was much easier to compare his work to Italian or Roman architecture than Nordic architecture. The more that you look into his archive however, the more that you see the people that he was connected with, and meant a lot for him, were often related to the North, whether it was Eero Saarinen or Arne Korsmo, a Norwegian architect he met on his trip to Rome in 1928. Korsmo was a connection that lasted Kahn’s whole life. So, I do think he was very connected both physically and mentally to the North, though he did not talk too much about it.

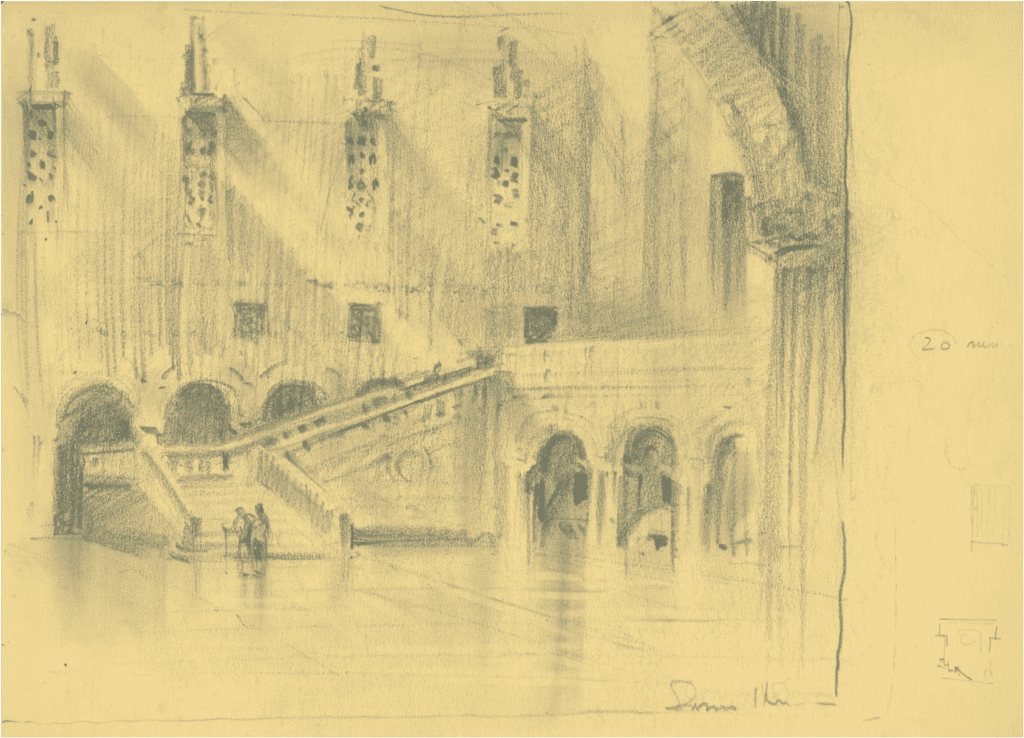

Kahn sketch made on his 1928 study trip, the Blue Room of Stockholm City Hall. (The Nathaniel Kahn Collection)

In 1928 Kahn spent a year travelling across Europe. Though he was a wonderful draughtsman there are very few sketches of buildings he saw in the Nordic countries but plenty from other regions. Does that seem mysterious to you?

I don’t think it’s that mysterious because you don’t sketch what you really know. You sketch the stuff you know less about. For him there was the curiosity of seeing Rome for the first time so it’s not so strange that he did not sketch what was the closest to him. And, as for new buildings he saw in the North, such as the library in Stockholm by Gunnar Asplund, I don’t think he would have sketched that. It would have been architecture for him and he would not have viewed it as a picture to remember.

In your book you talk about how you and Kahn shared a landscape and light. Can you describe this?

It’s a landscape that is very dark in the winter and very light in the summer, with long summer nights. The landscape connects the sea and the land, but it is the light that gives and defines its unique character. Though he was only five years old when Kahn left Saaremaa, I am quite sure that that memory of that light, and the memory of those Nordic days, never left him.

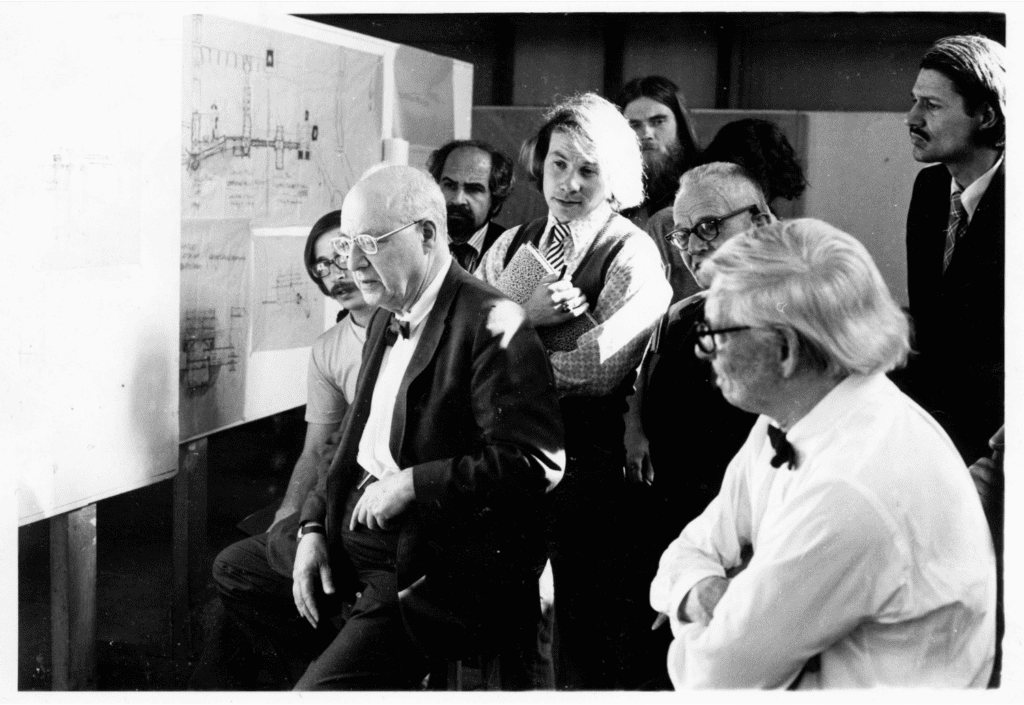

Louis I Kahn teaching in studio. Left to right: Norman Rice, Per Olaf Fjeld with notebook, Le Ricolais and Louis Kahn in profile with folded arms. “I teach myself when I teach others,” said Kahn (property of Per Olaf Fjeld)

What was Kahn like as a teacher?

He was a fantastic teacher but not for everybody in the sense that he had a language that you had to adapt to, a way of talking with the students that was not ‘do this’ or ‘do that’ or ‘can you correct that part?’ His teaching was not like that. He talked around the project; often recounting stories that could seem removed from the project itself. But through the way he talked, you gradually started to understand the project better. For many this approach was a puzzle. It also required a certain maturity in order to fully hook into it.

Can you talk a little about how Kahn’s masterclass reflected his own creative process, vocabulary and approach?

What struck me is how he was passionately interested in understanding the creative act itself. He talks about that in his silence and light theory. The theory goes: in silence is the will to express, and in light is the will to be made. He found the way these two come together to be the key issue in the creative act. A sense of wonder was also a key idea for him in teaching and in relation to the creative act in general. He wanted us to find the essence of a project and search for architectural depth and often talked about the relationship between knowing and knowledge. In a way he was saying that knowing is much more important for your own creative process. The knowing later gives way to knowledge.

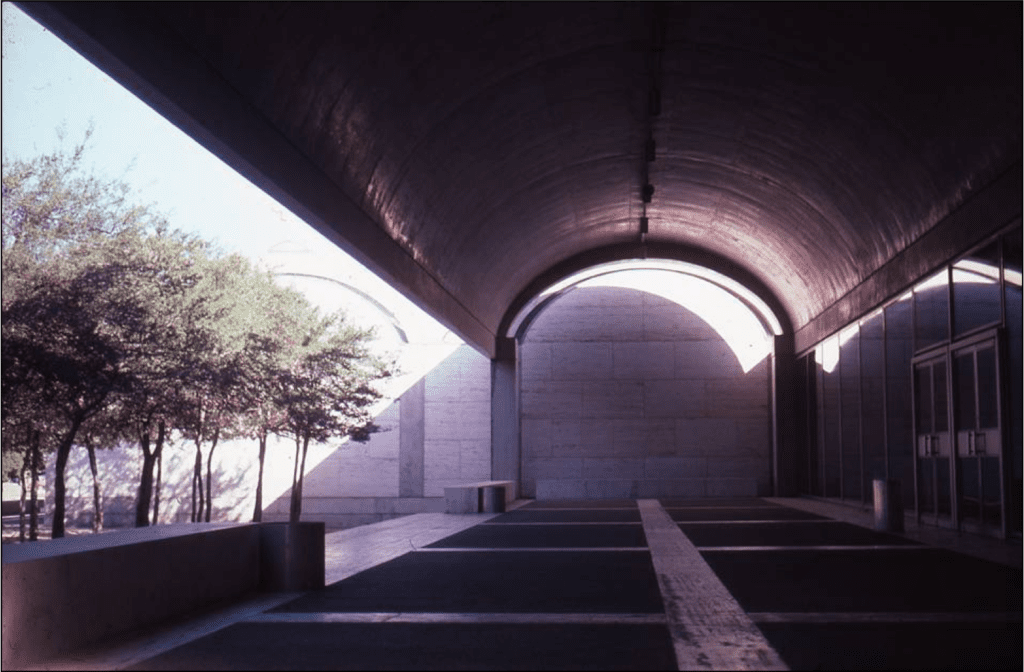

Kimbell Art Museum, designed by Louis Kahn (1966-72), (Photo: Per Olaf Fjeld)

When you talk about knowing versus knowledge, is the knowing something intuitive?

I think we all go through life having certain [eureka] moments where we discover something. Maybe you have three or four of those moments in your life, but you are not the same after such a moment, you have changed and matured. Kahn would comment on our ability to accumulate these ‘expressive instincts’, which were, in a sense, one’s available intuitive moments of knowing. He felt that to have the awareness of those moments was very important for the creative process. And that you had to start from scratch with each project. The less knowledge you apply in the beginning, the better the knowledge would be later.

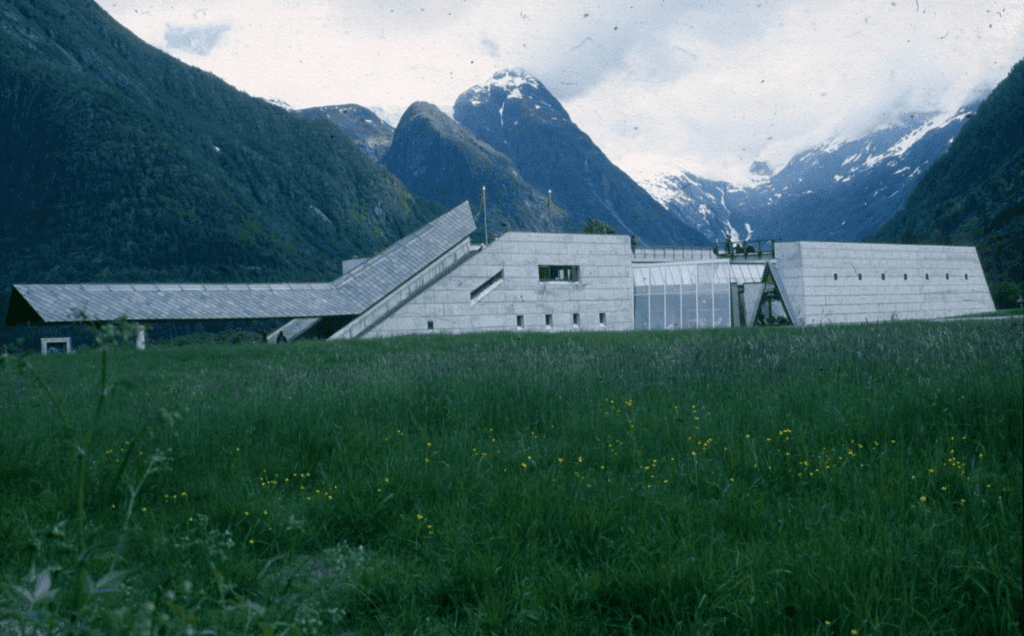

The Glacier Museum by Sverre Fehn (Photo: Per Olaf Fjeld)

What unites the work of Arne Korsmo, Sverre Fehn and Kahn in your view?

I would not compare their architecture, but they all shared a preoccupation with the relationship between material, structure and light. And they all believed in finding the core of a project and understanding the people you are designing for. Which then became the essence of the programme in itself. Korsmo was also a fantastic teacher and his teaching vocabulary and creative approach in class was very experimental, so not that different from Kahn.

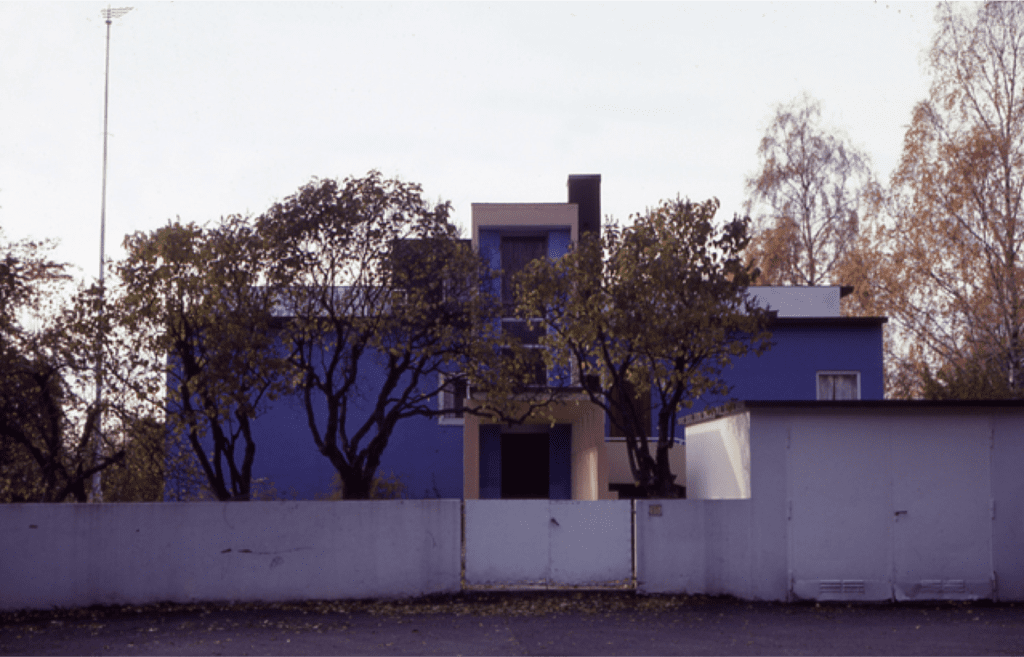

Villa Damman by Arne Korsmo, This house was begun soon after Korsmo returned home from the 1928-29 trip where he first met Kahn and completed in 1932. Later, Sverre Fehn bought the house and lived here for many years. Note: Sverre Fehn was a student of Korsmo. (Photo: Per Olaf Fjeld)

Sverre Fehn was a student of Korsmo’s and was an influential and inspiring teacher for the generation of architects that followed. They were three different personalities who were on the same wavelength in relation to the creative approach and who took teaching very seriously.

Has Nordic architecture had an impact on Britain?

Norway and the Scandinavian countries are small and we are way up north. This relationship to survival that I have mentioned, having less money and less food, though this has now changed, is still embedded. England has a completely different international history, where the rich at times owned the world. We are talking about a completely different type of scale in relation to building, a different demand, different programmes.

It would be surprising if Scandinavian architecture had the capacity to influence all that. Yet it has. And it’s embedded in what we have talked about, this idea of the relationship with the site, a precision of place and a preoccupation with material, structure and light. Respect for Scandinavian architecture, especially in the last 10 or 20 years, has become stronger in Britain. But architecture has also become more international now, so in a way what is built in London is also being built in Oslo.

Per Olaf Fjeld appears at the London Festival of Architecture, 10 June 2021 at 4pm: Louis Kahn 120 – The Islander (tickets available at Eventbrite)

Louis I. Kahn: The Nordic Latitudes by Per Olaf Fjeld is published by University of Arkansas Press

The Power of Circumstance: Architecture and Creative Independence, Six Lectures by Per Olaf Fjeld is available from RIBA Books

Top photo: Per Olaf Fjeld (Rolf Gerstlauer)