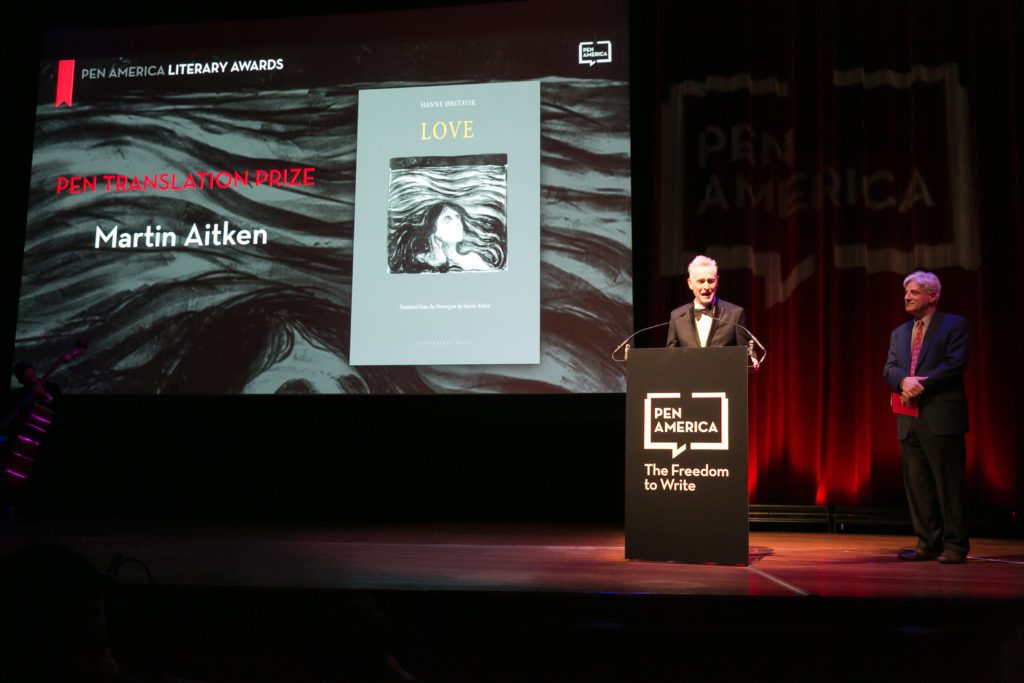

Martin Aitken’s recent translation of Hanne Ørstavik’s Love (Kjærlighet, 1997) won the prestigious PEN America Translation Prize 2019 and was shortlisted for the National Book Awards the same year. A contemporary classic of Norwegian literature, Love tells the story of Vibeke and her son Jon, who move to a small Norwegian village. The novel follows them through a single day – the day before Jon’s birthday – as an emotional distance stirs between them in the bitingly cold winter weather. It is a story of family, separation, solitude, and, of course, love, which has rightly been celebrated for its clear and honest style of writing.

Aitken, a British translator with a PhD in Linguistics, has translated both Danish and Norwegian literature, although the latter is a relatively new venture. However, following the praise for his compelling translation of Love, as well as his co-translation of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle 6: The End (2018), more Norwegian-British translations are likely to follow.

Without the translator’s craft, large areas of literature would remain unknown to foreign readers, something that Aitken referred to during his acceptance speech at PEN America Translation Prize: “Dostoevsky, Hamsun, Inger Christensen, Franz Kafka… These are all works we would be unfamiliar with, if it weren’t for the art of translation.” NA met up with Aitken to discuss the art of translation, the limits of academia and how to capture the essence of Knausgaard doing the dishes.

First, congratulations on the success of the translation of Love. What initially drew you towards the book?

Thanks, it’s very pleasing when a book gets the attention it deserves, which sadly doesn’t always happen, far from it. Sometimes even very good books can’t get a review. So being nominated for awards, and then actually winning one is immensely gratifying for everyone involved.

I hadn’t actually read Love until I was asked if I’d like to translate it. Of course, when I did read it I was in no doubt at all that I wanted to take it on. It’s such a small book, so low-key and so restrained on every level, and yet it leaves you so completely devastated.

I’d got involved with Archipelago Books in Brooklyn through translating Karl Ove Knausgaard, who they were publishing in the US, and Jill Schoolman, the publishing director there asked me if I’d be interested. So it was really just a matter of me being there in a way. Which is pretty much how I get most of my work. I wouldn’t know how to go out and pitch a book to a publisher.

Love was first published more than 20 years ago. In what ways, if any, was this noticeable while working with the text?

Yes, it’s interesting that a book can receive such a new lease of life. I don’t suppose it happens that often for original language works, but translation clearly makes it possible. The success of Love in America and now in the UK has been noted in Norway too, so in a way it’s looping back again. There was a stunning review in the Times Literary Supplement that said it felt like the novel could have been written yesterday, that it seemed like it was preserved in ice, which is my feeling too. No one’s got a mobile phone in the story. If they had, of course, things wouldn’t have needed to end the way they do.

Your first Norwegian translation (together with Don Barlett) was of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle 6. What made you start translating Norwegian, and what was it like to start with such a massive work?

I’m something of an imposter when it comes to translating Norwegian literature. Originally, I’m from the UK and settled in Denmark a good many years ago, so the Norwegian came by way of the Danish. I’d been translating from Danish for quite a while and had done a few books for Harvill Secker in London when one of the editors I’d worked with there phoned me up and asked me if I’d be interested. I was aware of the attention My Struggle had got in Norway and the momentum it already had in English, so my first reaction was certainly that I wanted to do it, but I hadn’t actually read it myself at that point. Once I did, there was no question of letting it get it away.

Like the majority of Norwegian writers, Knausgaard writes in Bokmål [one of the two official written forms of the Norwegian language], which is very close to Danish, so in that sense, at least, I wasn’t completely freaked. The End, as Book 6 is titled in the UK, came in at just short of 1,200 pages in the English. I did the first two parts, about 850 pages, while Don did the final 300 pages. The narrative parts – Karl Ove doing the dishes and getting the shopping in – were fairly straightforward, whereas the 400-page essay in the middle was obviously a different kettle of fish.

Basically, he’s writing without a filter, thinking as he goes along, analysing his way through a very difficult and bewildering poem by Paul Celan, the Cain and Abel story, the rise of Nazism, and referencing various philosophers and writers, so it gets a bit opaque at times, certainly, and often the challenge there was trying to actually pinpoint the meaning, to get a clear mental representation of what the author was trying to express, and then to render it in a way that preserved that sense of unfiltered immediacy, the unsmoothed nature of the original. The difficulty of doing that wasn’t so much the Norwegian as much as it was the writer’s mode of expression. But yes, it was a baptism of fire, certainly.

What got you into translation in the first place? Do you want to write your own books as well?

Literary translation was a conscious choice I made. I’d done a PhD in Linguistics and was lecturing in English, with tenure, the whole package, but I knew I wanted to be working creatively with language, and translation was an urge I felt every time I read a novel, a story, a poem. Academia is all about knowledge, which is the other hemisphere, and for me it was also a very stressful environment. I cared less and less about academic knowledge and more and more about that creative urge. I translate full-time, which still astonishes me seeing as how I work from such relatively small languages, but it does say something about the acceptance there is now when it comes to translated literature. I’ve no current plans to write anything of my own, but if someone would pay my bills in the meantime I could see myself trying.

Do you usually work closely with the authors while you are translating?

I think this is very much a matter of temperament. Some translators I know are quite dependent on establishing a working relationship with their authors as they go along, perhaps the author provides input chapter by chapter, or goes through the draft with the translator sentence by sentence, whereas in my case I need to be left alone. The creative space in which the author’s words on the page are transcended and become something other is of course hallowed. That doesn’t preclude some kind of interaction with the author at a later stage, and usually I’ll have a list of queries after the draft is done, but generally my collaborations are with editors rather than authors. I’m very sensitive about the translation, as sensitive as the author is about the original work, but I tend to be very open to the input that comes from copy-editors – and grateful too.

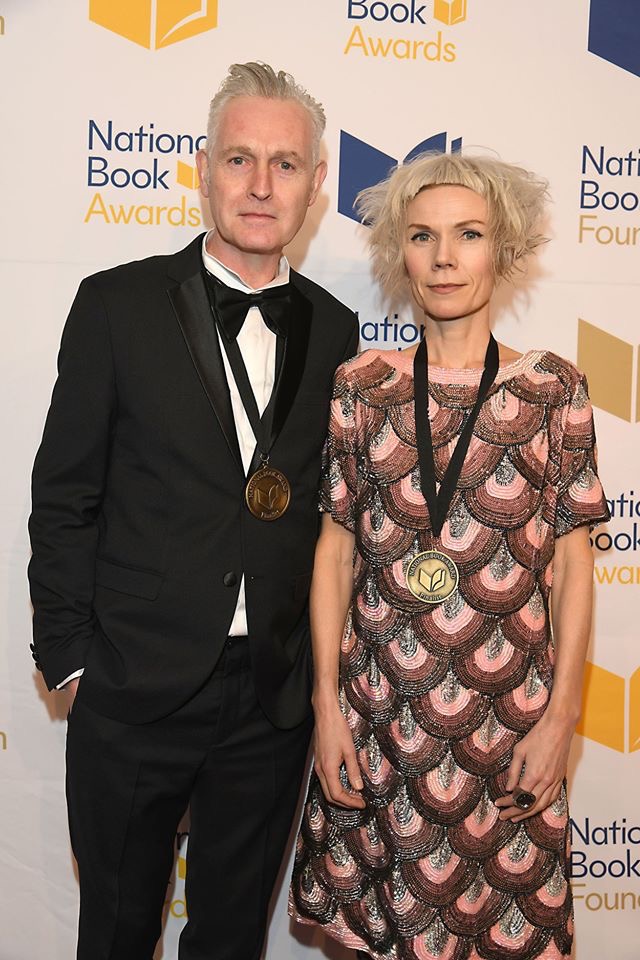

Martin Aitken and Hanne Ørstavik at the US National Book Awards 2018 in New York. (Photo: Robin Platzer/ Twin Images)

What are you currently working on?

A short Danish novel by Olga Ravn called De ansatte (The Employees). It’s a strange and mysterious work, very science-fiction, very Ursula K. Le Guin, and will be published later in the year, I think, by Lolli Editions in London. After that, in March, I’ll be picking up Hanne Ørstavik again, this time her novel Presten (The Priest) which won the Brage Prize in Norway in 2004. It’s a very different book from Love, but readers of Love will feel at home in the dark expanses of northern Norway. Again, this will be published by Archipelago Books in the US, some time next year.

What was your favorite Norwegian book from 2019? And what about ever?

Definitely Jon Fosse’s Det andre namnet (The Other Name). Absolutely magical, mesmerising. I’d shied away from Fosse for a while because of him writing in Nynorsk [“new Norwegian”, the second official writing form of the Norwegian language] which initially at least is somewhat more difficult for a Danish reader, but having taken the step I’ve been eagerly reading his other works too. Ever? That would probably have to be Hamsun’s Sult (Hunger).

Love by Hanne Ørstavik, translated by Martin Aitken, is published by And Other Stories

My Struggle: The End by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Martin Aitken and Don Bartlett, is published by Vintage