A new British Museum exhibition – currently closed due to the pandemic – explores the unstable climate and enduring culture of the Arctic. Ahead of Sámi People’s Day, Christian House discovers the creativity of the Sámi people of northern Scandinavia and north-west Russia highlighted by the exhibition.

The startlingly blue ‘four winds’ winter hat, beloved of the Sámi of Northern Norway, is a truly snug piece of headwear. But it is also a feather-filled weather vane, a Sámi reference to the changeable elements. It is just one of many striking objects that blend intricate folk art with unyielding practicality to feature in a new British Museum exhibition, Arctic: Culture & Climate.

The exhibition poses several questions. What is required to live in the Arctic? How is that existence changing? And how does culture manifest itself in such extremes? Intending to explore “the human experience of a living world of ice, land and water”, the exhibition is undeniably prescient. But as Jago Cooper, co-curator of the exhibition, notes: “Indigenous communities in the Arctic did not need Western scientists to tell them climate change was happening. They had observed the realities of the most recent climate changes for decades.”

A man’s ‘four-winds’ hat. Sámi; Karasjok, Norway (1940s-50s). Made from wool, fur, cotton and stuffed with feathers. Measures: 33 by 41 by 36 cm. (British Museum)

There are eight states with territory in the Arctic: Norway, Russia, the US, Canada, Greenland (Denmark), Sweden, Finland and Iceland.Across the region these communities account for some 400,000 people who continue to live, trade and create art in this extraordinary environment. In Norway, this refers to the far north of the country, the far-flung expanses in which the Sámi people have lived for centuries. This area is part of Sápmi – the cultural region of the Sámi people – and covers some 150,000 square miles, including segments of Norway and its bordering countries.

Historically the Sámi have stronger links to the east – Northern Russia and Siberia – than with North America. However, Jago Cooper notes, “Arctic peoples are currently extremely united politically. This exhibition is focused on climate change and issues of dramatic environmental change, because those are all common issues that bring different groups of Arctic people together.”

A pair of men’s trousers. Sámi; Karasjok, Norway (1940s-50s). Made from leather, fur, felted wool and metal. Measures: 70 by 128 cm. (British Museum)

Arctic: Culture & Climate is an unusual enterprise for the British Museum, which usually focuses on a period, a medium or an artistic movement rather than an issue. One of the key sponsors of the British Museum exhibition is the AKO Foundation, the organisation founded by Norwegian financier, art collector and philanthropist Nicolai Tangen. The foundation’s key concerns – improving education, the promotion of the arts and the mitigation of climate problems – are all important aspects covered by the exhibition.

The questions posed by the curators, Cooper explains, are no longer part of a fringe discussion. It is telling that Norway’s Office of Contemporary Art (OCA) recently announced that the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2022 will be entirely dedicated to the work of Sámi artists. “At this pivotal moment, it is vital to consider Indigenous ways of relating to the environment and to each other,” notes Katya Garcia-Antón, the director of OCA.

Márat Ánne Sara, one of the Sámi artists participating in the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2022 (photograph: Marie Louise Somby)

One of the biennale artists is Máret Ánne Sara from Guovdageaidnu in the Norwegian part of Sápmi, whose works incorporate materials deriving from the sustainable practice of her reindeer-herding family, including reindeer bones, hides and intestines. Her installation Pile o’ Sápmi, composed of 400 reindeer skulls and legal documents, was showcased at the art exhibition documenta 14 in Kassel (2017) and is now in the collection of the National Museum of Norway.

Máret Ánne Sara’s work blends topographical, anthropological and political aspects; she has become the figurehead of an interdisciplinary art movement that broaches issues such as community displacement and reindeer culling through a variety of artistic practices. “We have had guerrilla or street performances coming from this process and several independent art pieces,” she says. “I’ve been working very much in dialogue with other thinkers, not only artists, but also people from the academic field.”

A Sámi reindeer-skin bag with a drawstring handle and tassles decorated on both sides with a cross motif (20th century). Made from reindeer skin, felted wool, glass and ivory. Measures: 45 by 25 by 2.5 cm. (British Museum)

One activity which unites the indigenous communities represented in the British Museum exhibition, whether in Norway or Alaska, Siberia or Sweden, is a reliance on reindeer herding. “The common thing with all Arctic peoples is that they live extremely far north and they don’t use agriculture,” says Jago Cooper. “Therefore, the entire basis of the relationship with the environment, and with the natural world is completely different.”

Animals remain the focal point of Sámi culture: they are considered ‘non-human persons’ to be revered as much as utilised. In the exhibition, this relationship can be seen in an early 20th-century spoon carved from reindeer antler and decorated with an incised drawing of the animal: it is a practical item which invokes the ‘life spirit’ of the creature from which it originated.

Carved spoon made from reindeer antler with incised reindeer-decoration in pigment. Sámi, originally from Sweden or Norway. Dated from before 1927. (British Museum)

This, Cooper explains, “is material culture that tells the story of this connection between people and planet and everyday objects that capture the choices people have made in relation to the environment. There is, he says, a “resilience of innovation” that is specific to those who live in the Arctic. Sustainability and the daily choices relating to resources possess life and death importance. In the exhibition catalogue the curators state that the Sámi possess “a disposition that sees the potential in all things”. Indeed, when Europeans first encountered the Sámi in the 13thcentury, they were impressed by their inventiveness and resourcefulness.

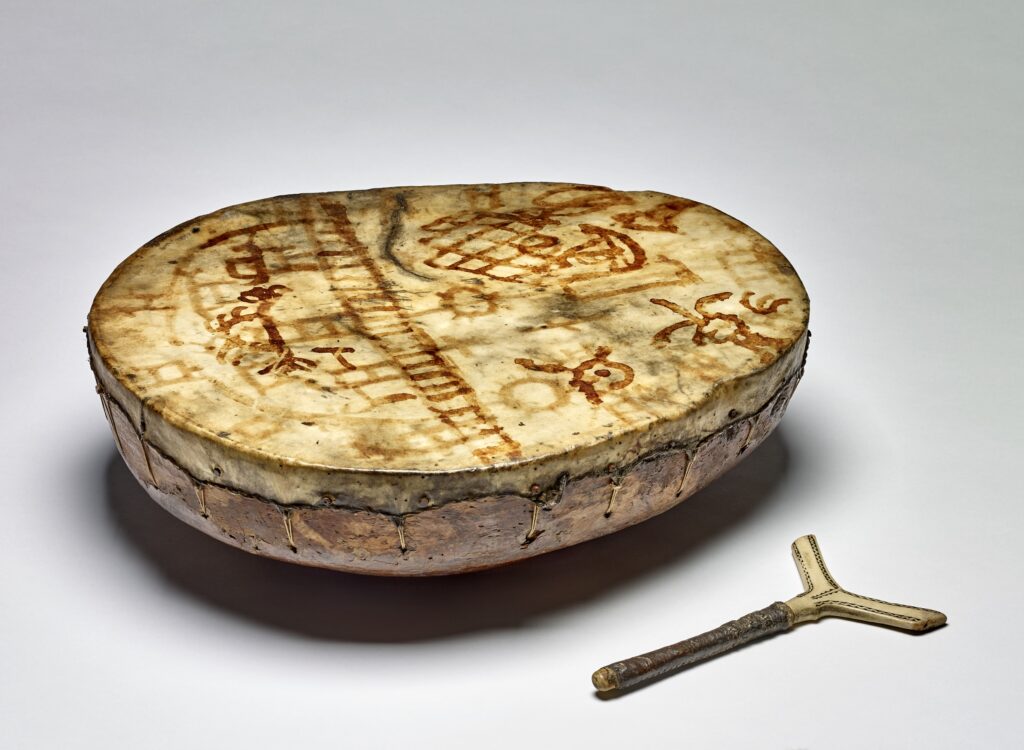

The Sámi artefacts on view at the British Museum – clothing, tools, toys, weapons and drawings, among many other items – reflect a larger aesthetic which spans the entire polar region. For instance, the bright hues on Sámi dress reappear in the floral patterns on smoked moose-hide boots worn by the Gwich’in people of Alaska; and the dyed figures displayed on 17th century Sámi drum-skins mirror those both on 20th century Russian drums and on Siberian mammoth tusks from the Late Stone Age. Such motifs echo through different times and places.

A man’s ‘four-winds’ hat and outfit. Sámi; Karasjok, Norway 1940s–50s. Wool, fur, cotton, stuffed with feathers. Leather, fur, felted wool, metal. Trustees of the British Museum.

As well as indigenous perspectives on Arctic object-making and histories, the British Museum has considered climate change in the region “through the lens of weather”. Both scientists and Indigenous elders, notes curator Amber Lincoln, “have observed climate in the Arctic becoming warmer, wetter and more varied.” In Sápmi, meteorological fluctuations have always been venerated: early Sámi noaidi– spiritual leaders – would communicate with wind and thunder gods through trance-like drumming on instruments made of reindeer-hide.

A 17th-century Sámi shaman’s drum and beater from the Pite region, decorated with dyed motifs. Made from wood, reindeer skin and antler, this particular object was a bequest from the British Museum’s founder Sir Hans Sloane. (British Museum)

One constant, however, is the Sámi love of vibrant tints. “For me it’s the colour,” says Jago Cooper. “The colour of material culture set against the contrast of the landscape, that’s what I love. A colour-scape of humanity, of reds and blues, which is overlaid over a natural environment which is often just white.” Visitors to the British Museum can find a perfect example of this brilliance in a Sámi woman’s red “horn hat” which must have appeared like a poppy on a page in the pale expanse of the tundra.

Woman’s ‘horn hat’ – known as a ládjogahpir. Sámi; Northern Norway (dated before 1919). Made from wool, horn, cotton and silk. Measures: 52 by 19 by 17 cm. (British Museum)

And this colourful relationship with the natural world, Cooper observes, is matched by an equally bold philosophical perspective of looking at the environment from within: “It’s that idea of ecology with a living integrated system of which you are a part.” Through all the weather changes, the Sámi – and their Arctic neighbours – have remained vivid constituents of a breath-taking landscape.

The Arctic: Culture & Climate exhibition at the British Museum is presently closed due to the Coronavirus pandemic. However, the museum is staging a series of online events.

On 5 February the British Museum will be hosting a special online celebration of Sámi culture, ahead of Sámi People’s Day on 6 February. It will explore how the Sámi way of life can remain strong and resilient in the face of climate change and other challenges, while remaining hopeful for the future.

Top photo: Umiaq and north wind during spring whaling. Photograph by Kiliii Yuyan (b. 1979) Inkjet print, 2019. (Photo: Kiliii Yuyan)