What happens when a psychologist can’t get to the truth of the matter? Norwegian Arts finds out from Helene Flood, a trauma specialist turned novelist who has taken her clinical practice into the realm of fiction.

In Helene Flood’s debut thriller, The Therapist, Oslo youth psychologist Sara finds that secrets are harder to unpick when they’re in your own marriage. When her husband Sigurd goes missing and she discovers that he has been lying to her, Sara’s seemingly happy – and rational – life begins to unravel. And then the police arrive.

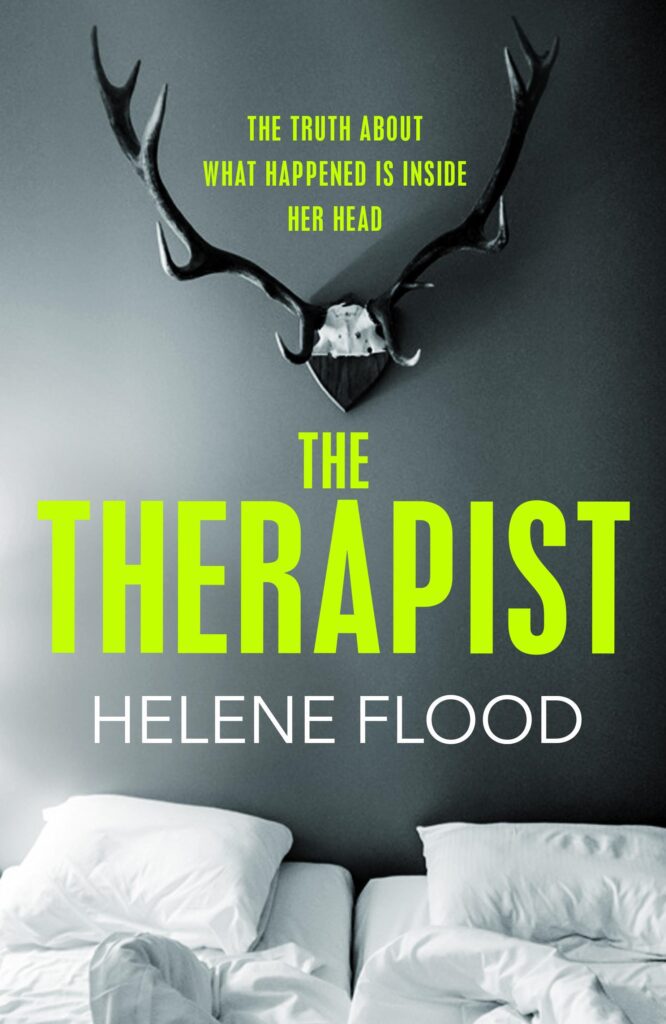

The Therapist by Helene Flood (MacLehose Press)

Flood obtained her doctoral degree on violence, revictimization and trauma-related shame and guilt and now works as a psychologist and researcher at the National Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress in Oslo. Her second novel, The Lover, has just been published in Norway. As The Therapist is released in Britain, in an elegant translation by Alison McCullough, Flood talks to Norwegian Arts about trauma narrative, unreliable spouses and sharing a cabin with Agatha Christie.

“Everything is done right in Helene Flood’s suspense debut.” Dagbladet

Are there professional considerations for a therapist writing a thriller about a therapist?

There are certainly ethical dangers. I’m not a practicing psychologist at the moment, I’m working in research and have done for the last ten years. I think if I hadn’t done that, I don’t think I could have written this novel. If I was still receiving patients that would be really difficult. Sara, in my novel, is a child and adolescent psychologist whereas I worked with adults. But then at the same time there is always the fear that someone will recognise something.

Helene Flood (photo: Julie Pike)

Are any elements of the novel based on real life?

I wanted to separate my researcher identity from my novelist identity and I came to realise that you can’t do that when you write fiction. You have to use, to a certain extent, your experience just interacting with people. No character is based on someone. So, I can’t say, oh yes, that’s my cousin. But – and this will freak you out – I can see a bit of me in all the characters.

Do you see parallels between the fields of psychology and literature? After all, Shakespeare and Freud cover similar ground.

That’s an interesting idea. I use a little bit of the same part of myself. As a therapist, you empathetically have to try to imagine what the world looks like from your patient’s point of view. I don’t have to agree with you but I have to understand your motivations. It’s a little bit the same when you write a character; you want to get inside the head of that character and understand why he or she does what they do.

Is it about coming at storytelling from opposing directions: one analysing, the other projecting?

I think so. I work with trauma psychology and trauma treatment often focuses on the trauma narrative, the story of the trauma that happened to you and how that can be integrated into the narrative of your life, so it is a coherent story of your life. I think in that perspective a lot of psychology is also about storytelling.

In creating Sara, was the aim to have a therapist who is struggling to put her own theories into practice?

Sure. Making Sara a therapist was interesting on many levels and this was certainly one of them: she is a professional in helping people sort out the mess that is in their life and then she has some rather large black spots when it comes to her own life. The classic psychologist is someone leaning back and observing, perhaps not engaging that much in conflict herself. It’s fun turning the tables. And in this book, it’s us who observes her and she has to engage with her story.

And to use the therapeutic room is interesting because it’s this room where you’re supposed to share your deepest darkest secrets, you’re supposed to be completely honest about who you are. And then we know that people very often lie in therapy. In the end, that’s a tremendously difficult thing to do, to be completely open about your weak spots. People are afraid that their therapist will reject them. Just ending a session might be seen as a rejection.

To what degree is The Therapist about the difference between knowledge and assumption in our everyday lives?

Lies are central to the novel. And the many ways we can do that: the lie of omission and the lie of commission. You have these close relationships where you’re supposed to feel safe and it’s a very threatening idea that people can hide stuff from you. That maybe you don’t know your loved ones as well as you think you do. And then – and this is a big theme in therapy – there’s the notion that on some level you might know but to preserve a relationship, your sense of security, you decide not to touch it. And what does that do to you?

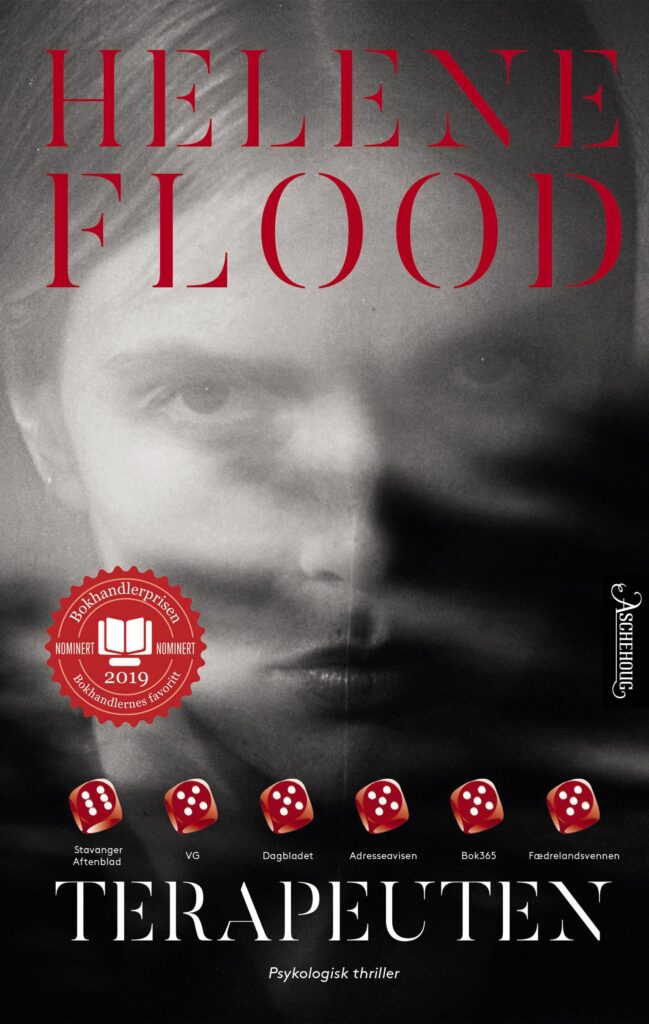

The original Norwegian cover of The Therapist (Aschehoug Forlag)

Did the structure of a therapy session influence the structure of your novel?

I don’t know. I’m a much more brutal author than I am a therapist.

The novel lends itself to comparisons with the work of Hitchcock and Daphne du Maurier – were these influences?

I’m someone who reads a lot of different stuff and I’m not necessarily a crime reader. I read a lot of Agatha Christie when I was very young. In our family cabin we used to have this old paperback from the 1960s which we read a thousand times.

When I’d finished my PhD, during which I read a lot of non-fiction, and was on maternity leave with my son, I picked up Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn and became fascinated with it. What interested me was how she made the story of the marriage of these two people an integral part of the book. Not just as background, it’s central to the plot.

Another recent Norwegian thriller, Agnes Ravatn’s The Seven Doors, also addresses the complicated relationship between doctors and patients. Is this a particularly Norwegian concern?

It would seem like it. Actually, I was on stage with Agnes talking about this. She is talking about transference in her book and I’m thinking about counter-transference. It’s something about power. Your physician or psychologist is a very powerful person. You’re in this relationship which is supposed to be equal – you’re both adults – but there’s still something about the person you tell everything to, that sees you either physically or metaphorically naked. It’s easy to project onto your doctor but it also sometimes goes the other way, and obviously that’s an abuse of power.

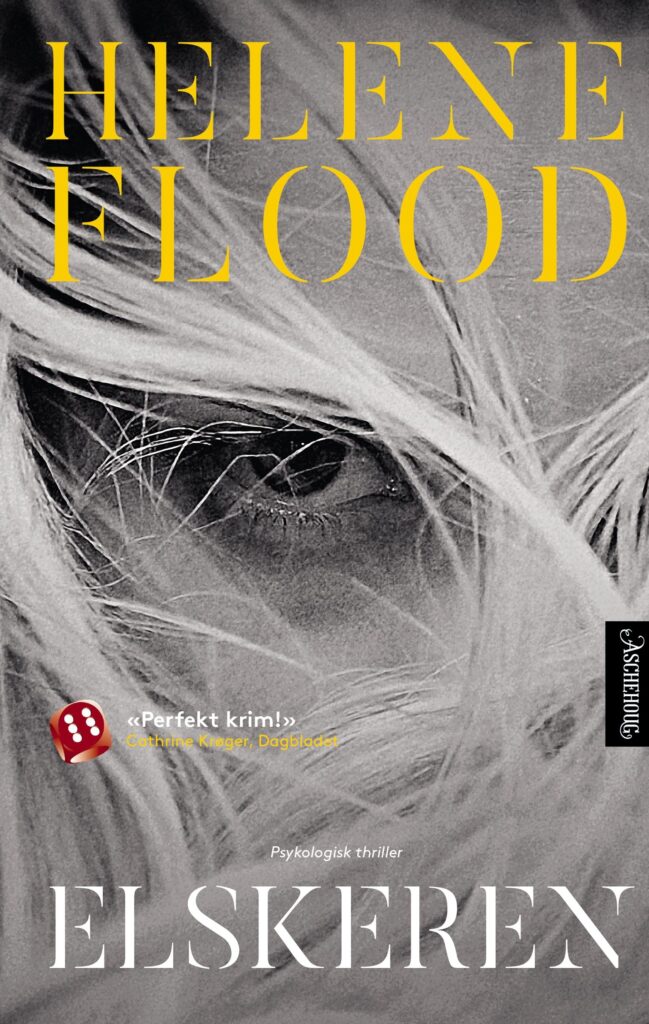

Norwegian cover of Helene Flood’s second novel, The Lover (Aschehoug)

Can a therapist empathise too much?

That can happen. If you’re going through a divorce – life happens to therapists as well – you might not see clearly the marital problems. But the idea is you don’t share this. That would probably not be very constructive to the patient.

And can the reverse happen – can a therapist be too clinical in their personal life?

I think maybe you should ask my husband that question.

Have you had any reader feedback from patients or colleagues?

Not from old patients – happily. I was wondering how my colleagues would feel about it. I’m describing a therapist who is not the world’s greatest therapist. Everyone has given me good feedback. Probably they’re holding something back. Some people asked: “So is this how you are as a therapist? Oh…ok…”

The Therapist by Helene Flood is published by MacLehose Press

A virtual launch of The Therapist will be held on Zoom on Thursday 8 July, 6.30pm. Register at Eventbrite

Top photo: Helene Flood (Julie Pike)

Read more literature articles from Norwegian Arts.