Where:

Southbank Centre

Website:

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances”. Shakespeare’s familiar words from As you like it is an appropriate epigram to illuminate the works of Norwegian artist Marianne Heske. If these words be true then the artist and her viewers are all complicit in the act of observing and therefore actively participating in her artwork.

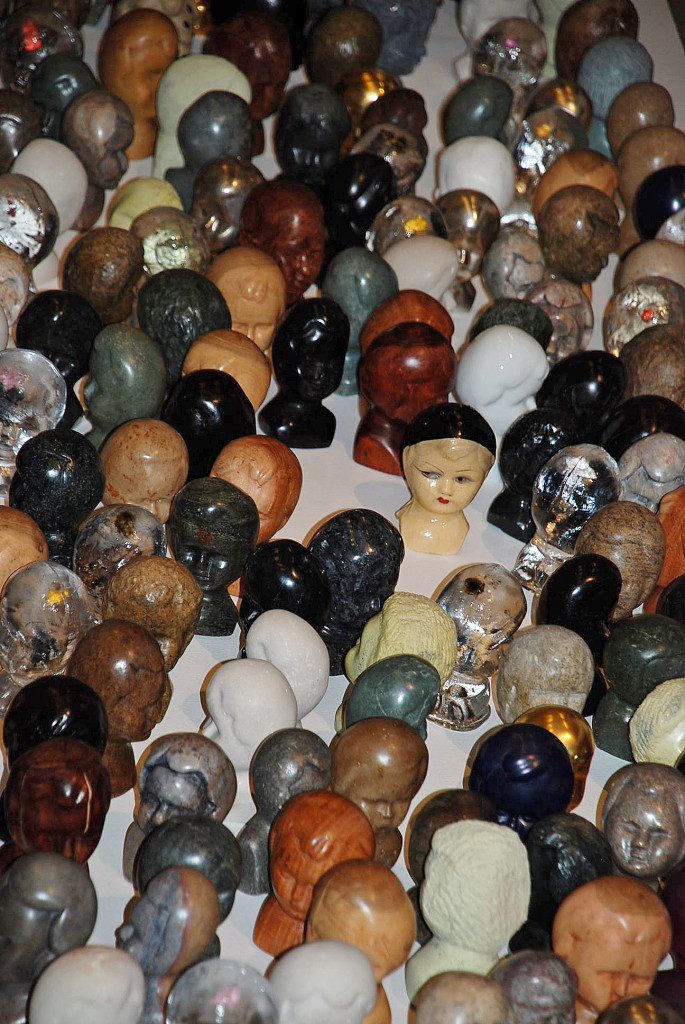

Gordian Knot – Necklace, an installation that Norwegian artist Marianne Heske has made for the Royal Festival Hall is composed of her now familiar to those who know her work – dolls heads. Here she chose to use over 200, choosing those made in Nepal inlaid with precious metal, gold and silver to make her long chain of over 20 metres long that spill onto the floor forming a Gordian knot, a knot that is almost impossible to untangle. Arriving in London to select the materials for this installation Heske visited the Southbank Centre and observed a huge variety of people coming to concerts, lectures or just sitting around eating and enjoying the diverse atmosphere. In a sense it was a microcosm of the life that she had observed as a child.

Marianne Heske – Gordian Knot – Necklace. Photo: Kristin Baann Asdal

Visible from along the river outside the building as well as from those climbing the grand staircase to go to concerts, she knows that the viewer will project their own spiritual and artistic beliefs onto the work. Whether it be simple curiosity about their rich materials, or awe at the repetition and scale many readings are possible for the many diverse visitors. We read the sculpture merely as a large necklace with all the implications that jewelry carries. Is it a rosary or worry beads? Is it a chain of decoration, imprisonment or devotion? She is curious as to how increasingly she sees people who seem to want to look as anonymous as her dolls instead of revelling in their diversity. “My dolls are French but why are all young people now looking like robots”. A lot of people are projecting something specific on them but there is nothing specific about them.

Growing up in the remote west of Norway Marianne Heske was the older of two daughters of a hydro-engineer, a director of the local electrical factory who enjoyed reading philosophy and a mother who read many books. Tafjord, their small isolated village, was cloaked in the shadow of the humbling mountains and was a microcosm for all society: the rich and poor, the old and young and the occasional mad person. While it was small it was not provincial. Heske vividly recalls as a child she was given freedom: to roam, appreciate nature and play. She begged her father for the huge wooden packing cases in which the turbines arrived for the electricity factory and with them formed a microcosm of the village containing a doctor’s office, the shop (the village only had one) and the telephone exchange to play in with her friends. She did not create a school room as “I did not much like school,” she says laughing, but then there was not a lot of it “as our teacher often went fishing to catch salmon in the nearby river”. She was very observant, climbing high above the village and as it was very steep, “the people looked very small so it was like a puppet theatre.” She would observe the inhabitants going about their daily business: farming, shopping or going to the doctors. Everything within the village was open for all to see. She recalls going with a friend to visit his sick grandfather and being there at the moment of his death – “his spirit left his body”. In the summer she recollects the sounds of avalanches as water would stream down and cracking of rocks as they would bounce down the mountainside. This openness to nature and her acceptance of the cycles of seasons and life has become part of the fodder of her work.

Marianne Heske’s HEAD N.N. in Torshovdalen park in Oslo. Photo: Sverre Chr. Jarild

Completing her first artistic studies in Bergen she moved to study at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, France arriving there after a stay in Czechoslovakia where she had observed the determination of artists who were prepared to go to jail for their beliefs. While at a flea market in Paris, she discovered a box of dolls, boys and girls, probably intended as the tops of marionettes. She was drawn to them partly because there were so many and partly because there was something robotic about them, as if they were merely waiting to be animated. Heske has manufactured large quantities of heads using the original doll as a template and they have become a key material for her installations. Heske says, “each is different, reflecting their makers and where they come from.” Amongst them there are fine white china ones made in China, and ebony, crystal and beaded ones made in Africa. A large bronze head scaled up from the original now sits prominently in a park in Oslo.

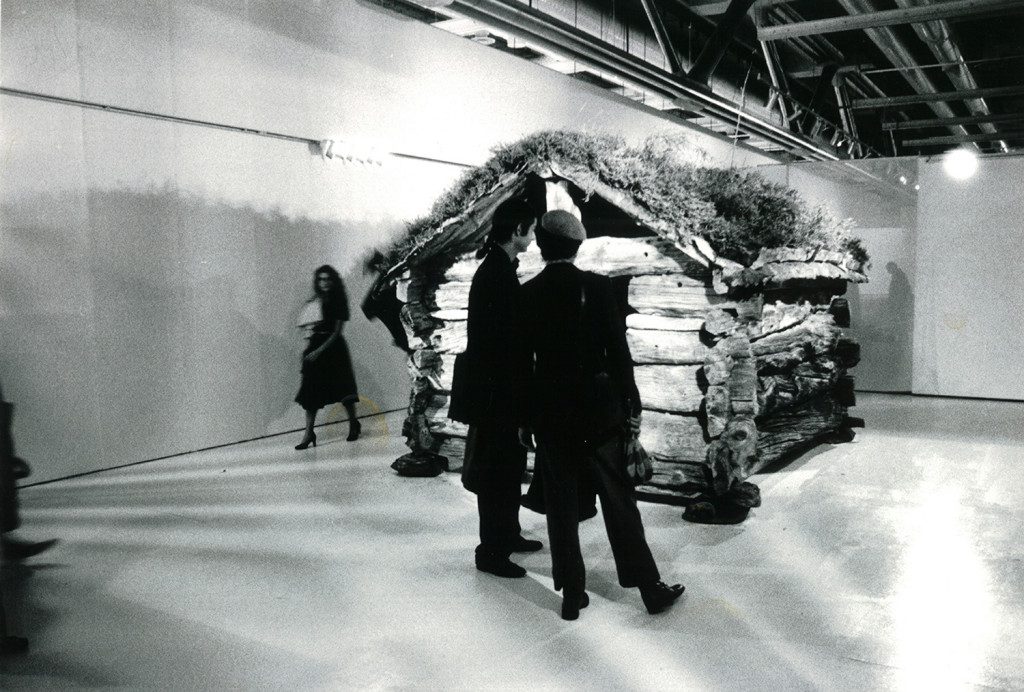

In the 1980s when Heske returned to Norway from her studies her ideas were difficult for local Norwegians to accept. She started to do videos and also making sculptures sometimes incorporating the found dolls but it was difficult to pigeon-hole her practice – neither painter nor sculptor. She was not ignored though and in 1980 she made a work for the XI Biennale de Paris, Gjerdeløa, an installation in which she moved a 350 year old log cabin, from northern Norway to Paris. The hut, constructed initially to store hay for herders, was exhibited in the Pompidou Centre and later returned from Paris to Norway, where it was exhibited at the Henie Onstad Art Center outside of Oslo, before subsequently being returned to its place of origin exactly one year after it was first dismantled to take to Paris. Gjerdeløa has been recognized by art historians as a key work in Norwegian art history in general, and in Norwegian Conceptual art in particular.

Marianne Heske – Project Gjerdeløa at Centre Georges Pompidou

Heske drove the hut to Paris herself and helped install it in Paris. She chose not to tell any local artists what she was doing. This was the early 1980s and political art was in the ascendency. She says in particular Norwegian male artists wanted to start a revolution with America – it was the war in Vietnam and here she was, a woman bringing something truly humble to a great new institution, the Pompidou in Paris. The museum bestowed the humble hut with authority and Heske played with that idea. Just as the position in the Royal Festival Hall bestows Gordian Knot – Necklace with a meaning beyond its individual elements.

Heske has traveled widely to India, Africa and China where she has commissioned and amassed a variety of dolls in various materials. None vary very much from the initial French dolls but each carry the unmistakable stamp of those craftsmen who made them. On her travels she photographed people interacting with the dolls heads giving them each both a collaborative freedom and authorship.

Marianne Heske – Global Groove

Heske never played with dolls when she was a child but as an artist she tells me without any shame that she plays every day. “I did not have time to play with dolls. I play with dolls now.” She still in her 70s immerses herself in nature, skiing and driving both her car and her wooden boat into nature in the fjords. She remains curious and like all genuine artists it is her ability to observe deeply and ask questions while setting a compelling scene that demands answers that sets her apart.

Marcel Duchamp once famously said “the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.” The only time Heske seems to lose patience with me is when I query whether the site influences the choice of her material saying dryly, “If I should do an installation here at the Festival Hall I would not do the same installation in a Chinese restaurant – it is my role to catch the spirit of the place”.

Necklace is part of Southbank Centre’s Summertime festival, as well as Nordic Matters – a year-long programme of Nordic arts and culture at Southbank Centre throughout 2017.

When:

14 July – 31 August

Tickets:

Free admission.

Norwegian Art