Brooding, dark, and often troubled, the detectives of Scandinavian crime fiction are the new anti-heroes of our time. The popularity of Scandi-noir may have begun with TV programs like Mammon and The Killing, and the novels of Stig Larsen and Jo Nesbø, but in Norway at least, crime fiction has been around for a lot longer than the trend.

Far from being a fad, crime novels are considered to be part of a long and highly regarded literary tradition of storytelling. Where they’ve often been considered quick and easy reads in the UK rather than sophisticated literature, in Norway, literary authors can switch genres to write crime without being accused of dumbing down.

Oliver Møystad, is a senior advisor for Norwegian Literature Abroad (NORLA), an organisation which helps get Norwegian literature translated into other languages. ‘Norway has a strong tradition of storytelling writers, many of whom are now writing crime fiction,’ he says. ‘They keep up their quality as strong storytellers and a writer can write crime without losing credibility and still be taken seriously.’

An egalitarian platform for authors to be given their due for their writing has no doubt helped fuel the current boom in Nordic crime fiction. But Norway’s tradition of crime storytelling as we know it today actually began in the 1970s with authors like Bergen-born Gunnar Staalesen.

Inspired by the American writer Raymond Chandler, he created a long-running series of novels centred around the character of the private eye Varg Veum. As with many British and American detective characters, Veum is far from perfect – an alcoholic, divorced, ex-social worker, he bears comparison perhaps to Ian Rankin’s Scottish detective John Rebus. But unlike US or UK crime fiction, Staalesen’s protagonist, as in many Scandinavian detective stories, holds up a mirror to a larger social injustice. Scandinavian crime fiction often has a dual purpose, serving as a literary form of social criticism, to shed light on wider societal wrongs.

For all their personal failings, detectives like Varg Veum, care deeply about those who are the weakest in society, especially children, and often at the expense of their own personal lives. Social conscience is a theme that can be traced throughout Norwegian crime fiction into the Hanne Wilhelmsen novels of Anne Holt, and to Karin Fossum’s Inspector Sejer series. In each of Fossum’s stories, the character Sejer doesn’t just want to know whodunit, but also why, forcing the reader to feel the extent of pain caused by each crime, on every character, not just the victim, but the investigator and perpetrator too.

Jo Nesbø’s dark-humoured Harry Hole novels share this broader focus, and for lots of British readers it was Nesbø who gave us our first introduction to Norway’s particular take on crime writing. And we would be mistaken to lump the novels of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden together. Norwegian writing has its own distinct voice, and Møystad believes the Norwegian landscape plays a significant part in setting the country’s crime writing apart from the rest.

‘In books by authors based in the north and west of Norway in particular, landscape and nature play a large role,’ he comments, highlighting writers like Trude Teige who lives in a small village outside Ålesund, Frode Granlund who lives on the Lofoten Islands, Monica Kristensen who lives in Svalbard, and Asbjørn Jaklin from Tromsø. ‘The elements are very present, playing a part in the action, in all these books. It’s definitely something which sets them apart from other Scandinavian crime writers.’

Of course our appetite for Nordic crime has kept him and his colleagues very busy with the onerous task of facilitating translations into English. ‘It’s often difficult to translate the dialogue, with all the nuances of how people speak, be it dialect or personal variations, into English. In Norway, for example, a character can speak a dialect and still expect to be taken seriously.’

Wherever the appeal lies, whether it be the moralising social conscience, the beauty and wildness of the scene-setting, the angst of the lead characters, the quality of the writing, or all of the above, there’s some good news. For avid Nordic crime readers among us, there are plenty more Norwegian crime stories being written and translated to keep us gripped for a good while longer yet.

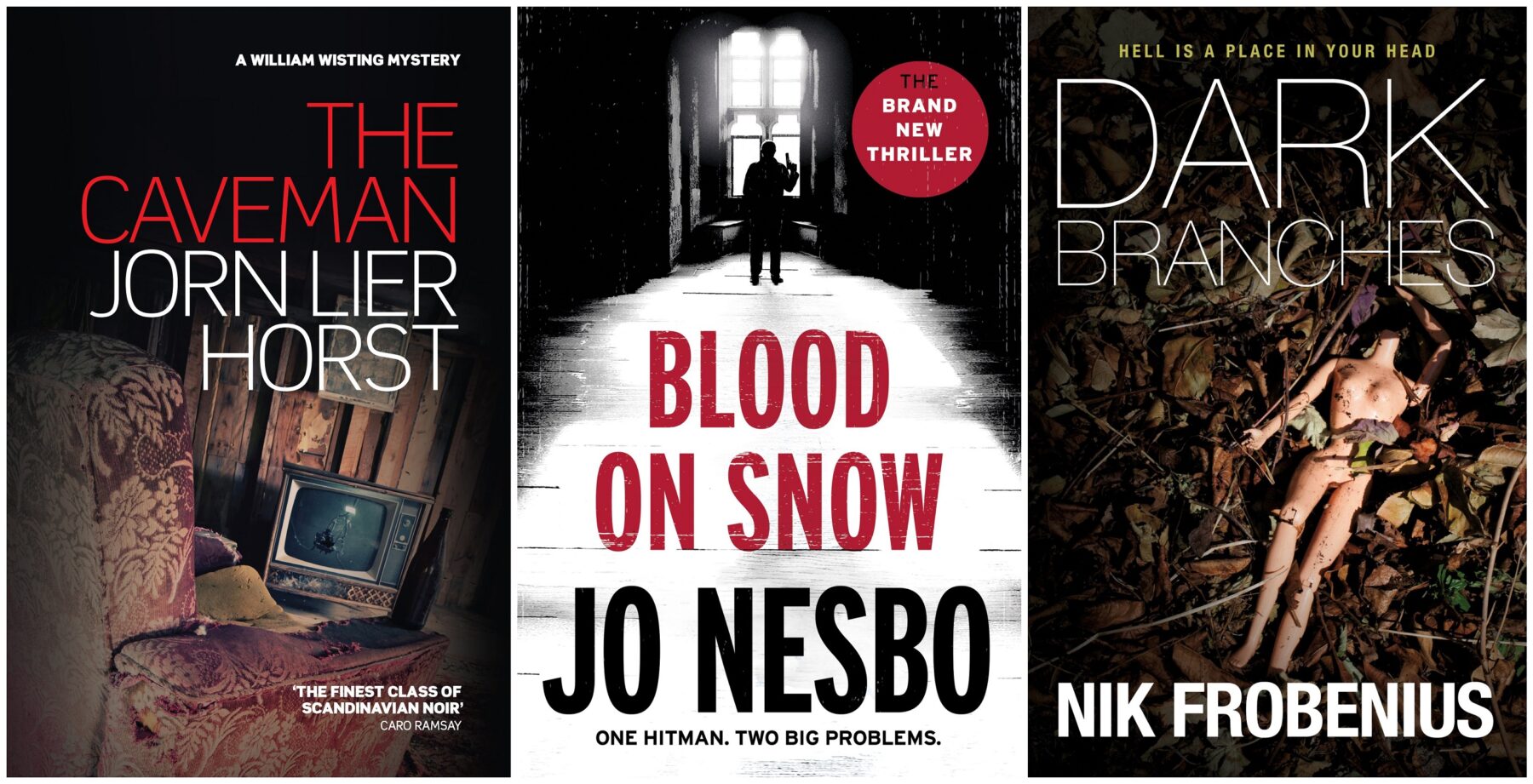

Latest releases:

Jo Nesbo – ‘Blood On Snow’ out now on Harvill Secker

Gunnar Staalesen – ‘We Shall Inherit The Wind’ out now on Orenda Books

Jørn Lier Horst – ‘The Caveman’ out now on Sandstone Press

Nik Frobenius – ‘Dark Branches’ to be published in July by Sandstone Press