War and aggression, pestilence and poverty, extremes of climate and exploration: these themes have shaped many of the greatest Norwegian paintings, works that have focused on resilience and – ultimately – the triumph of tenacity over adversity. At a time when Norway, as with all nations, is tackling the challenge of the Covid-19 pandemic, there is some solace to be garnered from these pictures, many of which were created in the eye of the storm. Some of the works illustrated below reference struggles head on, others obliquely, but they all bear testament to the empathy and united fronts that have seen Norway prevail over the centuries.

Edvard Munch

Self Portrait with Spanish Flu, 1919 (Norwegian National Museum)

Autumn Ploughing, 1919 (Norwegian National Museum)

Two paintings by Edvard Munch, both from 1919, tell a pictorial tale of revival. Norway’s greatest painter knew all about enduring misfortune; as a child he lost his mother and beloved sister to tuberculosis. He also overcame the strains of mental illness and alcoholism. And, in 1919, he was struck down with Spanish Flu. In these two paintings from that year, Munch first captures himself, through a pared-back figurative study, in the grip of illness. And then, in the autumn, he paints new beginnings, as he shifts his focus to the farmers in the neighbouring fields as they plough the soil in preparation for new growth.

Christian Krohg

Sjømen I Stormvaer

Christian Krohg, Munch’s friend and fellow Bohemian, also recognised the potency of harrowing moments. In this snapshot in oils he celebrates the courage of lifeboat men as they attempt a rescue in a raging squall. The painting is one of several in which the artist portrayed, in compositions of fierce movement conjured from visceral swirling oils, everyday mariners performing heroic acts in the maelstrom of the sea.

Christian Krohg

Struggle for Survival, 1889

Another masterpiece by Krohg delivers a city scene of charity: a soup kitchen in late-19th century Kristiania (now Oslo) is besieged by mothers and children. Today, food is still provided for the city’s homeless through various charitable organisations, including the Salvation Army, and private initiatives such as Oslo Soup.

Peder Balke

Lighthouse on the Norwegian Coast, 1855 (Norwegian National Museum)

The lighthouse was a favourite subject of Peder Balke, the 19th-century artist who painted in some of the most isolated, brutally beautiful parts of northern Norway. With his lighthouse studies, he summoned the chaos of nature and the ingenuity utilised to protect people from its havoc. And Balke’s interest in salvation extended beyond the canvas: he was also a social reformer who developed a whole suburb of Oslo in which workers could build their own homes with financial assistance.

Nikolai Astrup

Old Woman with a Lantern, circa 1895-99

Nikolai Astrup, Old Woman with a Lantern (Oil on trouser fabric, The Savings Bank Foundation DNB / KODE)

It is not always the most dramatic images that tell the most dramatic stories. This early neo-romantic painting by Nikolai Astrup reduces a world of hardiness to a single figure. The elderly woman battling her way between two cottages against a barrage of falling snow highlights the trials of daily life for many peasants at that time. Astrup wrote of the work: “Early winter morning (fantasy) Snowdrifts. Grey on grey, white and blue, light grey sky with dark grey flakes. The only element not fitting into this grey scheme is a lantern carried by a dark grey figure.” Here is the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. The picture also illustrates the practicality of a young artist with limited resources – it is painted on fabric torn from a pair of old trousers. At the top of the picture the seam of a trouser leg is still visible.

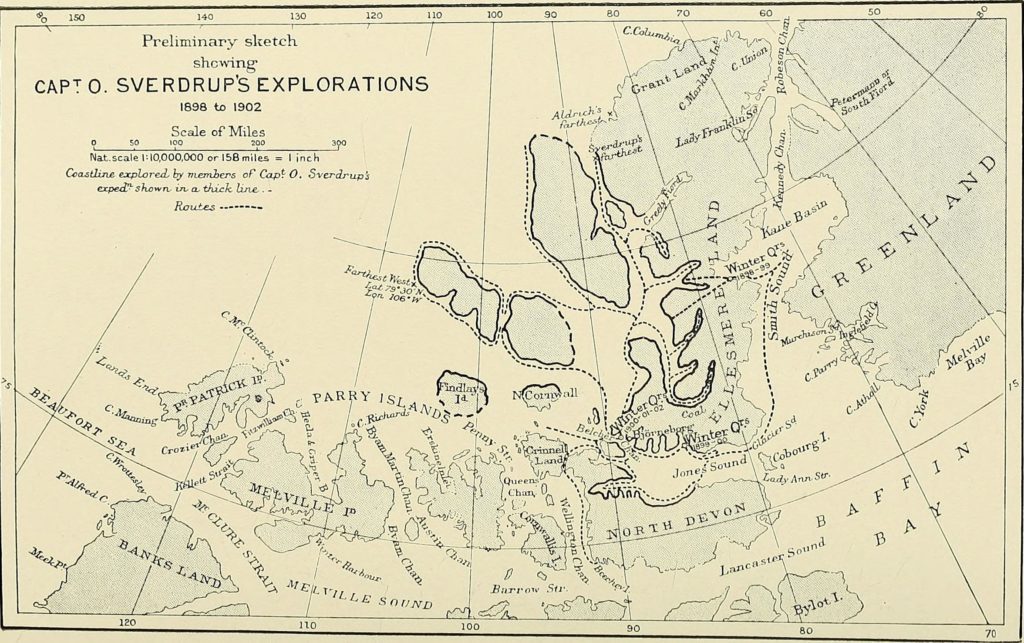

Sverdrup’s Map

Illustrated in the National Geographic Magazine, 1898-1902

Preliminary sketch showing Capt. O Sverdrup’s Explorations, 1898-1902 (National Geographic Magazine)

This maritime chart represents four years – 1898 to 1902 – of peril and privation for Otto Sverdrup and his crew as they plotted passages through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The men were on board the sail and steamship Fram, which also took Nansen, Amundsen and Wisting on expeditions. With Sverdrup, the vessel charted 260,000 square kilometres – more than any other Arctic expedition. This image records a phenomenal feat of survival against the elements: the crew overwintered – three times – in their frozen cabins. The National Geographic Magazine, which illustrated the map, praised the solidarity of the crew, stating that “without such harmonious work success was not possible.”

Gustav Wentzel

The Emigrants, 1903

The mass emigration of Norwegians to America was a defining episode in the country’s fortunes during the 19th and early 20th century. Nearly a million Norwegians left, spurred by famine and poverty in rural communities. This phenomenon was rendered in paint by many artists of the period, including Adolph Tidemand and Harriet Backer. In this particular painting, Gustav Wentzel depicts a group of emigrants as they set off on their long journey. Such departures left families split and a nation sapped of a generation. It also brought Norwegian culture to the Mid West of America, where it still thrives today.

Frank Wathne

Wartime Christmas Postcard, 1941

This Christmas card, drawn by the illustrator Frank Wathne, was created during the Occupation of Norway in the Second World War. At the time, wearing traditional red Nisse hats – and even their representation – was banned by the Nazis who saw them as overtly nationalistic. Wathne’s postcard was perhaps the sweetest symbol of Norwegian resistance created during those bleak years and is now in the collection of the Norwegian Resistance Museum in Oslo.

Hannah Ryggen

Grini, 1945

Hannah Ryggen, Grini, 1945, Tapestry weave in wool and linen, 191,5 x 168,5 cm, © Trondheim Kunstmuseum, Norway, VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2019.

Hannah Ryggen has become synonymous with the idea of fighting against the odds. A committed pacifist, she used tapestry as a barrier to Fascist oppression in the first half of the 20th century. She used her own herd of sheep for the wool and foraged for materials such as lichen and berries to create dies. In this woven rug she threads together an image of her husband, the artist Hans Ryggen, as he is released from the Grini prison camp at the end of the Second World War. She once described her works as “200% Norwegian”.

‘Oslove’ Hearts, 2011

Finally, an elevating piece by an unknown hand, a work of gracious and humanistic graffiti. Heart motifs – of which this was one of many – sprang up on buildings and walls across Oslo in the wake of the terrorist attacks of July 2011 – symbols of unity in the face of appalling events.

Top picture: Nikolai Astrup, Old Woman with a Lantern (Oil on trouser fabric, The Savings Bank Foundation DNB / KODE