More than three quarters of a century after the Occupation of Norway, an art installation on the fringes of Oslo looks to celebrate the ongoing importance of freedom. Christian House talks to its co-creator, Vebjørn Sand, about this moving, innovative and timely open-air exhibition.

This December an elegant old-timer travelled from the forests of Oslo to the heart of London in commemoration of the wartime bonds between Norway and Britain. This handsome and bristly pilgrim was an 80-year-old spruce selected to be this year’s Trafalgar Square Christmas tree, to be enjoyed by Londoners and visitors alike and to underline a still-pertinent tale of shared values and shared troubles.

The Norwegian Christmas tree has been a present from the city of Oslo to the people of London for more than seven decades, given in thanks for the assistance Britain offered Norway during the years of Nazi Occupation from 1940 to 1945. This year, however, the importance of those events is also being marked back in Oslo’s woods. Above the city, on the horizon line, sits Roseslottet – the Rose Castle – a majestic art installation of golden structures, paintings and sculptures, all dedicated to the people and ideals that saw the nation survive the war years.

The project is timed to the 80thanniversary of the beginning of the Occupation and the 75thanniversary of Norway’s liberation. It is the creation of installation artist and painter Vebjørn Sand and his brother, Eimund, a sculptor. Along with their dedicated team, the brothers spent three years bringing Rose Castle 2020 to fruition and it will remain in situ until May 2021. At its entrance stands a statue of a white rose, emblematic of the group of German students, who took that name in their own non-violent resistance against the Nazi regime.

Talking to me from his home just outside Oslo, Vebjørn Sand explains that the origins of the project can be traced back twenty years, to when he created two further installations on the same site (an ‘Ice Castle’ and a ‘Peace Star’). Following those works, Sand moved to New York where he lived for 17 years. When he returned to Oslo during that time people would ask him when another installation would adorn the forest. With his brother’s participation and with the impending anniversary of the Occupation, he realised, that “suddenly the time was right.”

Described as an “art park” – allowing for education and reflection – the Rose Castle is positioned in a clearing high above the city, close to the final stop of the Metro line at Frognerseteren. Its location is pivotal. “You can see it from all over Oslo,” says Sand. “One of the most iconic views from the city centre is the Holmenkollen ski jump. You look just a little higher up and there’s the Rose Castle.”

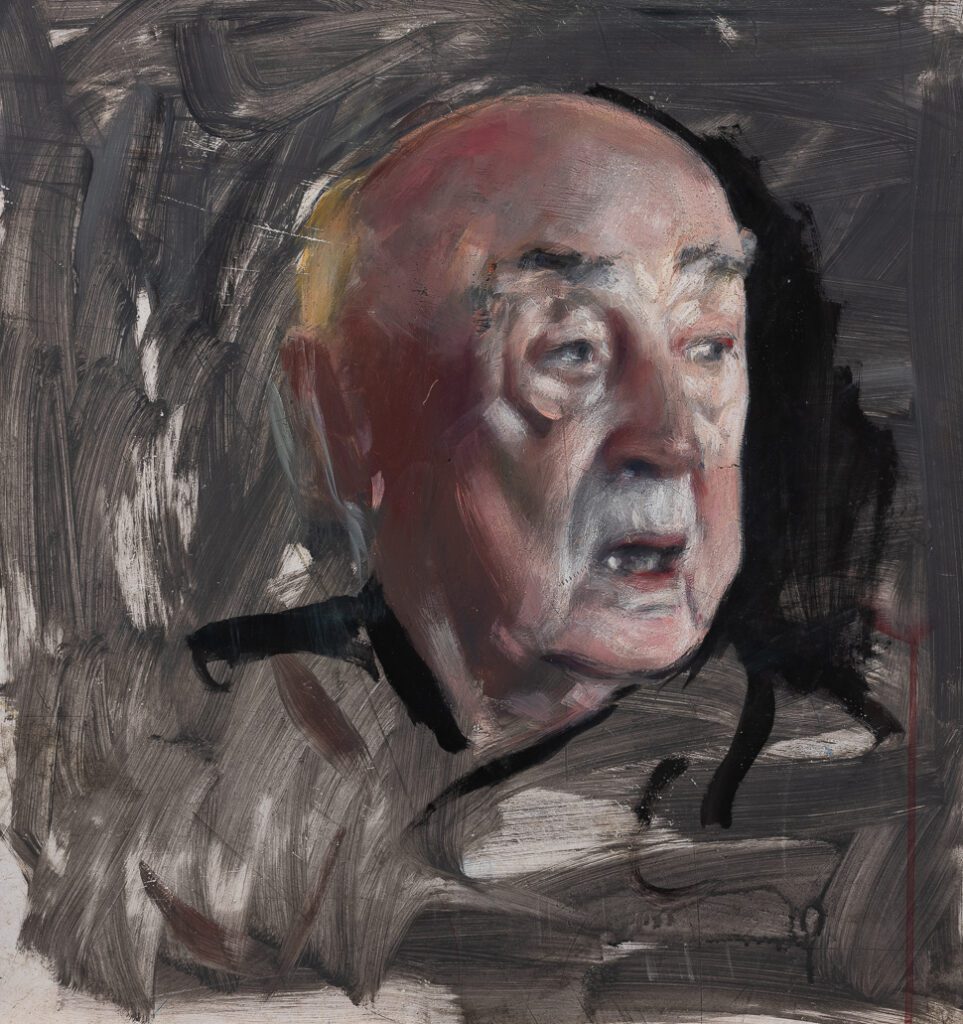

Several years ago, the Sand brothers approached the Norwegian government with their proposal, bolstered by the support and mentorship of Kjell Grandhagen, the former chief of the Norwegian Intelligence Service. Grandhagen died in 2019. His last public appearance was in April of that year at the press announcement for the project. “He was a noble man, a fantastic man,” notes Sand. His portrait of Grandhagen stands prominently in the Rose Castle grounds.

Celebrating the wartime bonds between UK and Norway was key to the Sand’s vision. They have a potent legacy. “That is something that is deeply rooted in the Norwegian atmosphere,” he says. “Without that help, that collaboration, it wouldn’t have worked.” That bilateral cooperation manifested itself in many and varied ways: fishing boats ferried equipment and people between Shetland and Norway in what became known as the Shetland Bus; Company Ligne, a special Norwegian SOE unit, trained in the wilds of Scotland; and Norwegian pilots flew in RAF squadrons. Similarly, British forces served in Norway, particularly in the early days of the conflict. And, of course, there was the dramatic escape of King Haakon, in June 1940 on the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Devonshire, which allowed him to set up a ‘government in exile’ in London.

The most prominent aspect of the Rose Castle is a series of five symbolic golden structures: a sail (representing the military and merchant navies); a tree and a mountain (representing the resistance movements of southern and northern Norway); an aircraft wing (for the air force), a quill (referencing the civil resistance and press) and finally the ‘Kongebjerka’ – the Royal Birch – the national symbol of the King’s stance against the invasion, inspired by an iconic photograph of King Haakon sheltering under a birch during a German bombing raid.

Collectively these structures address what was lost during the Occupation: “faith, democracy, rule of law, human rights, freedom basically,” states Sand. “And all of those symbols have a lot to do with the bonds and collaboration with England during World War Two.”

As visitors enter the Rose Castle, they come into a courtyard displaying portraits of 37 living witnesses of the period, from Norwegian troops to Resistance fighters to survivors of the Holocaust. There are also Russian and Ukrainian prisoners of war pictured, representing those held by German forces in Norway. For these portraits, Sand travelled all across Norway to visit these elderly witnesses. That journey, he says, “was the backbone of the project.”

Sand presents images of soldiers and civilians, men and women. It is a democratic gallery. Two pictures based on photographs of King Haakon – one from when he escaped to London and one from his return to Norway – are featured, as does a painting of a fallen German soldier. In his research, he scoured thousands of photos taken in Norway by members of the occupying forces. “After the war, in the 1960s and 1970s, they returned,” Sand notes. “They took their wives back.” As the organisers explain, the intention behind Rose Castle is “to tell the story of the war without demonizing or glorifying, central to the narrative is the individual and its choice.”

That generation, says Sand, “are not shy but they are humble. I walk into a home or a hospital, and sit next to them and they just need to trust me. I explain what I’m doing and then I take out my sketch pad and doodle sketches. It’s a slow and sensitive process. I joke that in the last three years I have gotten more than 30 new friends who are over 100 years old.” Sadly, some of his sitters have died since he visited them.

The passing of the wartime generation makes the forest installation particularly timely. In his speech at the 2019 press conference, Kjell Grandhagen stated that the principles fought for then are still under threat. “Rose Castle is not media hype, it is not a pompous commemoration project or a commercial business concept,” Grandhagen said. “It is the importance of remaining focused on our fundamental social values – and maintaining them – which has been the most important motivation for us.”

The experience shared by the British and Norwegians in the Second World War will always be remembered in Britain thanks to the raising of the annual Christmas tree. But, in Norway, the events of those five years continue to shape military tactics and an appreciation of Anglo-Norwegian relations. Tomas Adam, a trainer for the Norwegian Special Forces,teaches the history of the period to new recruits. “This means that our history not only shapes our identity, it will also help to influence our actions now and in the future. History used in such a context will be able to function as a moral and ethical compass.” And the ties between British and Norwegian forces is a key aspect of that lesson. “The moment the British organization Special Operation Executive (SOE) established the Shetland Bus and Company Linge, an important relationship between our nations also started. What started in 1940-45, continued after the war and into our time.”

Vebjørn Sand’s Portrait of Jakob Strandheim, the last survivor of the ‘Shetland Bus’ which ferried people and equipment between Shetland and Norway during the Second World War (Sandbox)

In amongst the pines, Vebjørn Sand’s paintings – his ‘Faces of History’ – also display that affiliation. Exhibited in the open-air, exposed to the seasonal elements, each is painted in acrylics on PVC panels and then sealed with an epoxy resin that includes UV protection. “We are taking the museum out into the woods,” Sand says. In addition to the artworks, the Rose Castle offers an education programme for participating schools and a series of concerts.

The installation marries the specifics of the wartime experience, exemplified in the paintings, with universal humanistic themes, as illustrated by the site’s geometric design, which references the civilisations of ancient Greece. The design also has a personal association: “That is something that Eimund and I learnt from our father, he is also an artist and works with geometry.” And aside from his projects with Vebjørn, Eimund runs a workshop specialising in developing geometric forms.

Due to the pandemic, the opening of the Rose Castle had to be postponed from May to June 2020 and the organisers have restricted visitor numbers in the months since, in line with advice from health authorities. Even so, some 100,000 people have already visited the site.

Sand’s father, Øivind, who was a child when the war began, compared the Coronavirus crisis with the invasion. As Vebjørn explains: “He said that in March it was the same atmosphere in this country as during the time of the Occupation, or the attack. Of fear and uncertainty. He said that he hadn’t felt it since 1940.” But, Sand continues, what followed – both then and this year – was unity.

The Rose Castle – Roseslottet – is on view in Oslo until May 2021. Take metro No. 1 Frognerseteren all the way to the end station