As fresh strains of Norwegian noir emerge, shaped by new and veteran authors, Barry Forshaw explains how a well-worn genre has received a chilly shot in the arm.

Norway’s cultural treasures are truly impressive. Apart from the writer Henrik Ibsen, the painter Edvard Munch and the composer Edvard Grieg, there are many artists who have encapsulated the national character – difficult and proud – in works of art that are quintessentially Norwegian. In terms of contemporary crime fiction, the country’s forbidding landscape – and the possibility for both the good and the bad to lose themselves in its vast reaches – is reminiscent of (but different from) the sprawling America of such writers as James Lee Burke. Similarly, the appeal to British readers may be that such canvases are far from the more geographically constrained brand of crime fiction practised in the insular environs of the British Isles.

Any discussion of Norwegian Noir should perhaps start with man who is not just its pre-eminent master but is widely considered to be the current king – in terms of book sales – of Scandinavian crime fiction. Those fortunate enough to have encountered Jo Nesbø have observed his understated, rather British humour and laser-like awareness of everything happening around him – the defining traits, in fact of his tenacious policeman DI Harry Hole. Novels such as The Devil’s Star (2003), The Redbreast (2000) and, most notably, his imposing 2007 novel The Snowman have propelled Nesbø to stratospheric heights – and his work also provides a coolly objective guide to fluctuations in Norwegian society.

Nesbø’s novels are epic in length. His latest, Knife, tallies some 500 pages. The similarly arm-straining Macbeth – a modern reworking of the Shakesperian tragedy – had a decidedly mixed reception, but Knife finds him back on form (although some readers will wish that editorial scissors had been wielded more ruthlessly). The novel sees Harry Hole falling off the wagon and waking after a binge to discover that his wife Rakel has been murdered. The new strain here? There is a more pronounced internationalism in the writing, with a side-lining of overtly Norwegian elements; it develops Nesbø’s avowed intention to reach beyond his countrymen and women.

One wonders if his Norwegian crime-writing contemporaries resent the Nesbø juggernaut. Thankfully recent arrivals appear unruffled – and a recent bestseller on Nesbø’s home turf is Heine Bakkeid’s I Will Miss You Tomorrow, which has already gleaned rave reviews for the writer, who grew up in the forbidding landscape of Northern Norway. Bakkeid’s protagonist is perhaps an over-familiar type – a washed-up copper obliged to redeem himself – but is richly and idiomatically drawn.

Bakkeid’s protagonist, Thorkild Aske, is a disgraced ex-policeman who has been kicked out of internal affairs and served a prison term. He has only one desire: to immerse himself in drug-fuelled reveries of the woman he loved and lost, the enigmatic Frei. And when Frei’s family approaches him to track down her young cousin who has disappeared on the Norwegian coast, the reluctant Thorkild feels obliged to help the family. But he is soon on a nightmarish odyssey in which his lost reputation may soon be complemented by his lost life.

Heine Bakkeid has something in common with the Icelandic crime writer Yrsa Sigurdardóttir: both wrote young adult novels while building up a store of horrific scenarios with more than a dash of Stephen King – narratives that burst forth terrifyingly in their subsequent adult novels. The Gothic elements in I Will Miss You Tomorrow are splendidly integrated into the crime plot, along with a strand of dark sardonic humour. It’s a novel that is as much about loss and guilt as it is about the solving of a crime. At a stroke, Bakkeid has entered the upper echelons of Norwegian crime writing.

At a crime fiction convention in Bristol a few years ago, the after-dinner speakers were dispensing the usual darkly humorous pleasantries to a chuckling audience: how they made a living from murder; how their spouses came up with ever-more ingenious ways of dispatching victims. But then the guest of honour, Karin Fossum, took the stage, and the bonhomie evaporated in a cool blast of Norwegian air. Fossum – possibly the most accomplished Nordic female writer of crime fiction at work today – was having none of the brandy-induced good humour that had preceded her, and her description of a real-life child murder was delivered point blank to a suddenly sober audience.

It was a salutary reminder that crime – however pleasurable on the page – has grim consequences in the real world. Fossum began her writing career in 1974. With such books as Don’t Look Back (1996) and He Who Fears the Wolf (1997), she has won numerous awards, including the Glass Key Award for the best Nordic crime novel. In 2018, The Whisperer – in which a woman receives a letter that reads “YOU’RE GOING TO DIE” – showed that Fossum’s talents are as keenly honed as ever. “It’s exemplary stuff, with the dismantling of the constrained heroine’s life brilliantly drawn,” noted The Guardian.

Another important female Norwegian writer is Anne Holt, who has had a host of careers, beginning in the Oslo Police Department. Subsequently, she founded her own law firm and was appointed Norway’s Minister for Justice. But it’s for her cutting-edge crime novels that she is most celebrated. While her work is shot through with the social commentary we have come to expect from Scandinavian crime fiction – she hardly paints a rosy picture of Norway – there is often a strain of Englishness to her work, reflecting her love of British ‘Golden Age’ crime.

There are so such influences in A Grave for Two (2019), however, which has a more generic, international feel, particularly in its unrelenting accelerando pacing. Her subject is an upscale Norwegian skiing community with its deeply competitive stars. Norway’s curious perception of its own identity through sport is an issue here, and the novel is something of a departure from Holt’s police procedurals; some may be wistful for her earlier work.

Attention has to be paid to Gunnar Staalesen, undoubtedly one of the finest Nordic novelists in the tradition of such masters as Henning Mankell. The Writing on the Wall (2002) is a radical re-working of Mankell-style material, but his most striking novel was to appear seven years later. A phone call from the past sets the narrative of The Consorts of Death, (2009, the 13th novel in the series about Bergen detective Varg Veum).

Staalesen tries to avoid the parochial in his writing. “As a Norwegian writer of detective novels,” he has said, “I am definitely conscious of writing within an international genre, and the inspiration for my writing comes from both American writers (Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald), British ones (always Arthur Conan Doyle, and – in terms of plotting, at least – Agatha Christie), as well as the great Swedes Sjöwall & Wahlöö. The small Nordic languages, in which we Norwegians can talk together and read each other’s books in the original tongue, creates for Nordic writers one big family.”

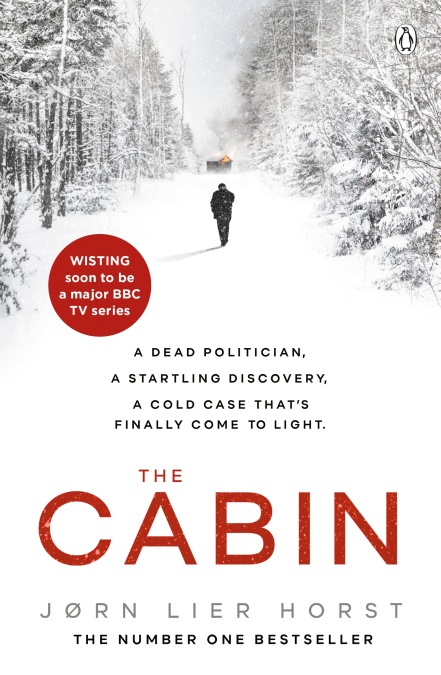

Urban rather than natural settings are the stamping grounds of ex-policeman Jørn Lier Horst, who was born in Telemark, Norway. Horst worked as a detective in Larvik, but the acclaim that greeted his debut novel in 2004, Key Witness, allowed for a change in career. That book was based on an actual murder case and brought a striking verisimilitude to the narrative. Horst’s William Wisting series of novels – soon to be dramatised by the BBC – has been extremely successful in his native Norway, enjoying similar acclaim in Germany and the Netherlands.

His new novel, The Cabin, is the second entry in the author’s ‘Cold Case Quartet’. It begins with the discovery of the body of an important politician, Bernard Clausen, who has been found in his cabin on the Norwegian coast, surrounded by a fortune in what appears to be stolen money. Chief Inspector William Wisting – as single-minded and tenacious as ever – learns that the late Clausen had concerns extending beyond politics into the country’s criminal networks. The book continues Horst’s move away from his more economical police procedurals towards heavyweight thrillers.

The spectacularly talented Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, a Swedish crime-writing team with a markedly Marxist perspective, might be said to have started the genre of Scandinavian crime fiction in the late 1960s. Surveying the work of Norwegian authors relatively unknown to British readers, such as Heine Bakkeid and Jørn Lier Horst, we find that the field remains vigorous in the 21st century.

I Will Miss You Tomorrow by Heine Bakkeid is published by Bloomsbury on 14 November

The Cabin by Jørn Lier Horst is published by Penguin

Top Photo: Heine Bakkeid (Harriet M. Olsen)