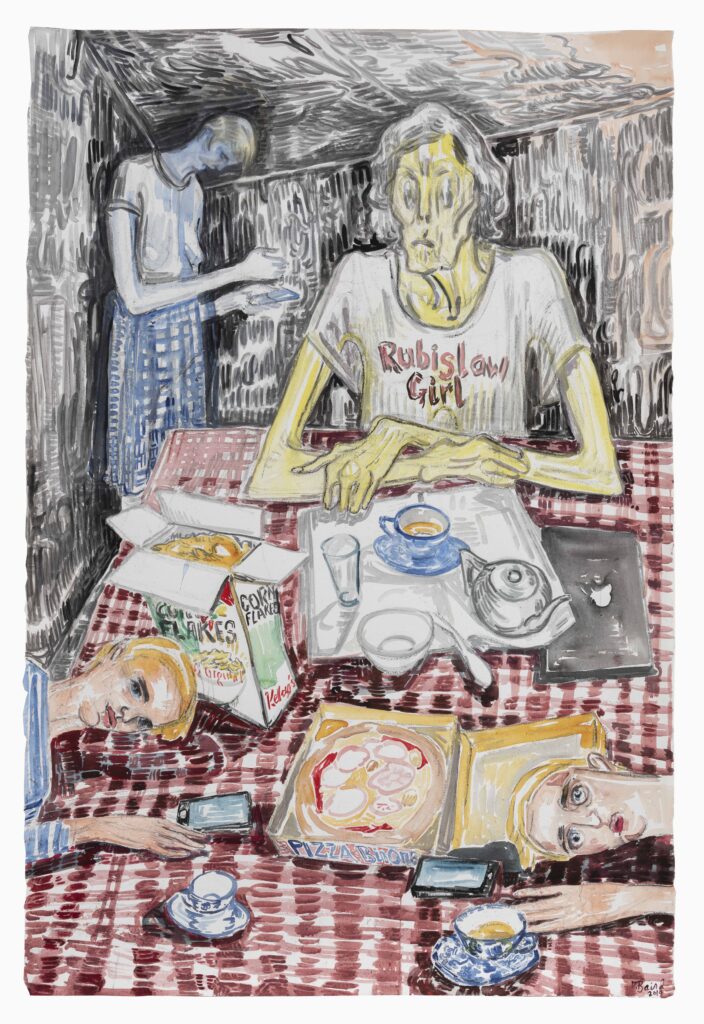

Born and raised in Oslo to a Scottish mother and Norwegian father, Vanessa Baird still lives in her childhood home and has been drawing almost every day for half a century. Her works, with their claustrophobic compositions and foreshortened perspectives, can be unsettling, but they are largely drawn from Baird’s everyday family life. They tell a slightly exaggerated version of the truths we so often don’t want to see, using humour to make them palatable.

Vanessa Baird, Rubislaw Girl, 2020, watercolour on paper, 100 x 150 cm, courtesy the artist and OSL

Baird’s first solo exhibition in the UK – If ever there were an end to a story that had no beginning – is currently on view virtually at Drawing Room, London. Norwegian Arts spoke to Baird about her inspirations and dedication to her practice, living with chronic illness, and her sense of identity.

Is it right that you refer to all your works – whether pastel or watercolour – as drawings?

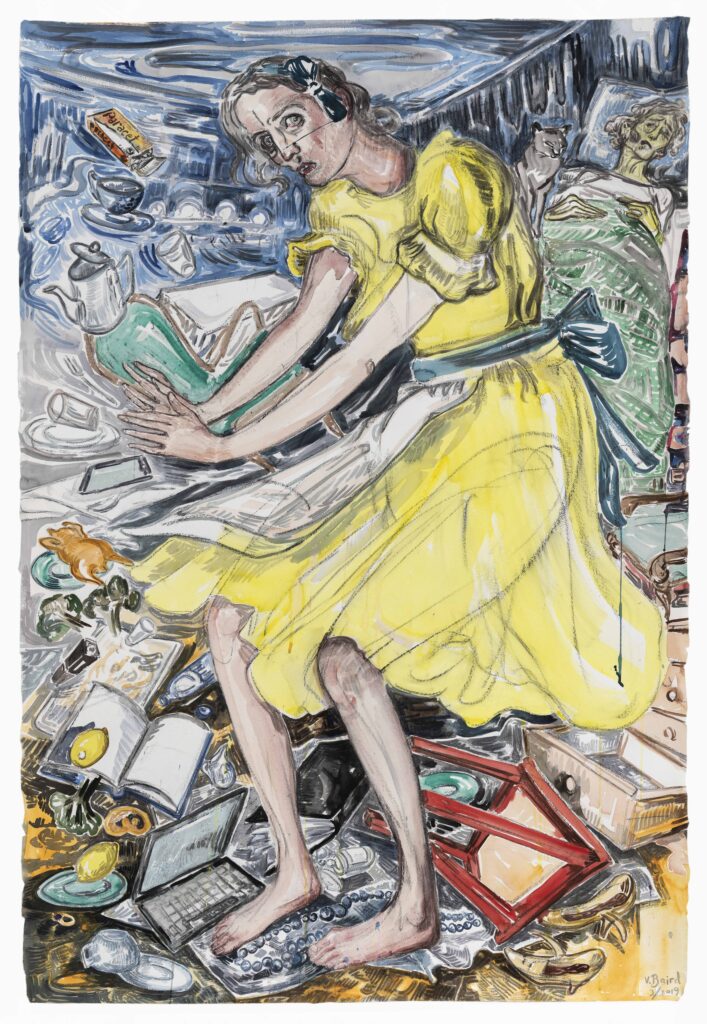

Yes, I draw with the paint, I draw with the pastels. I’ve always been confident when it comes to drawing, it comes really easily. I’ve tried working with oil paints, but I still drew. I only used lines. I always use lines. It’s a way of writing, really. I make plans for what I do, but not how I do it. With watercolours, I can work at home. I do lots of my work in the kitchen. I don’t have a studio in my house, or a living room, so I work in the space which is available. The fumes [from the fixative] and dust are therefore more of an issue, when I want to work with pastels. I’ve got a big studio on the other side of town, so I go over there as often as I can, and that’s where I’ll do that work.

Vanessa Baird, I had three kittens in the dryer, 2020, watercolour on paper, 100 x 150 cm, courtesy the artist and OSL

For your exhibition at Drawing Room, you have made a new body of pastel work, A Little Red Coat, a Pair of Beautiful Blue Trousers and a Green Umbrella Lost at Sea(2020), comprising a series of 12 paper scrolls, which wrap around the gallery walls, four metres tall and more than 14 metres across.

Yes. It’s a bit like doing sport – you want to keep going, running fast, showing off. It’s very satisfying, but physically you do get worn out, working on such a scale. It’s very strange with this work, and Covid, as I just put it in a roll, sent it off, and haven’t seen it installed. It’s the first time I didn’t help install my own exhibition.

Vanessa Baird’s paper scrolls on view at Drawing Room (courtesy of Drawing Room)

A lot of your inspiration comes from Scandinavian folklore. How important is it that the audience recognises your references?

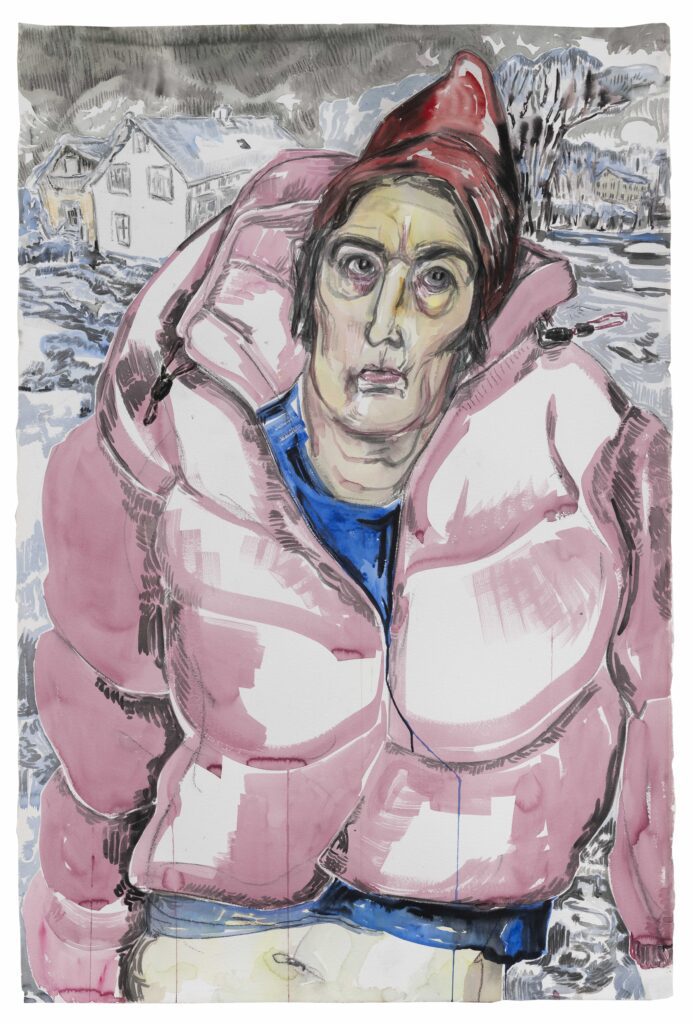

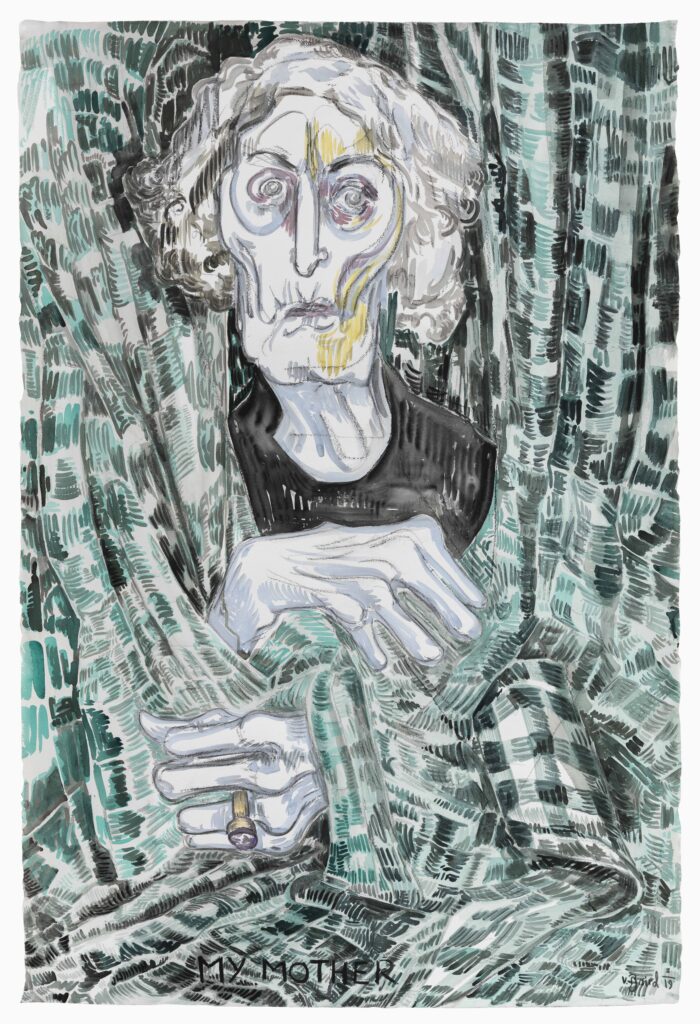

My approach to using the fairy tales – which I do far less now than I used to – has always been to take general figures from the story. For example, with Goldilocks, it would be the wolf. And they are stories that almost everyone will recognise anyway, not specifically Norwegians. There are versions of these tales in every language: by Italo Calvino in Italy, the Brothers Grimm in Germany, and so on. I use the stories, not as stories themselves, but as props. I use my mother as a prop all the time as well. She turns 90 this month, and I’m her carer. She’s very useful as a model: [as] an older witch though, not a sweet granny type. The only way to cope with family life is to give the people around me different roles in my drawings. I use them to tell a narrative. There’s nothing extra, nothing hidden behind what you see. I just put the people around me together as if it were a drama.

Vanessa Baird, The cherry blossom in my neighbour’s garden – Oh it looks really nice, 2019, watercolour on paper, 100 x 150 cm, courtesy the artist and OSL

How autobiographical is your work overall?

Everything in it is true. Maybe it’s worse than what you see in reality. I rewrite things while I’m drawing them.

You have a series of watercolour self-portraits – Red Herring Prednisolon Ciclosporin (2014-18) – on view, which you made when you were being treated with these medications for a chronic illness.

Yes. I have a kidney problem, and I have had to take these awful medicines on and off since I was born. They have nasty side effects, which get worse when you’re older. Those medications in the title were to suppress my immune system. I couldn’t cope with them and had to stop taking them. But, while I was on them, I made these self-portraits. I date them, so you can follow through where I was mentally.

“I have drawn every day for 50 years”

I wasn’t doing it as therapy, though, that’s not a good way to do drawings. I just did them as a way of keeping up my daily exercise. I have drawn every day for 50 years. Then, suddenly, I had 150 or more, and so I decided to publish them as a book. It was a way of providing medical information and insight – not for other patients, but for doctors.

Vanessa Baird, My Mother, 2019, watercolour on paper, 100 x 150 cm, courtesy the artist and OSL

You’ve talked about your drawings as being a bit like writing, with the use of lines and putting stories into them. You also put actual text into your work sometimes.

Yes, I try to avoid it, but I do. The titles are also a very important part of the work. I’m really into reading, even though I’m a heavy-duty dyslexic. I collect other people’s sentences. I nick them out of books and adopt them. When I see other people’s artwork, I often go in with a critical eye, because it’s my trade, but reading has that distance.

Do you always use English words and phrases?

No, but all my family are Scottish. I was born in Norway, grew up here, and stayed here, but I don’t have any Norwegian family. It’s very much part of my identity that I’m not Norwegian.

The word “home” appears a lot in your work, which ties in to what you’re saying about identity. Is it right that you still live in the house in which you grew up?

Yes. I did my Masters in London at the Royal College of Art, but, apart from that, I’ve always been here in this house. It didn’t matter to me that I didn’t leave, because I’ve always been working. This wasn’t my plan, but I didn’t have another plan either. I just fell into it and I’m still here, drawing. That’s my only interest, it’s a nice way of living. I received a state grant when I was 40, which means I get paid until I’m 67. It’s not a huge wage, but it keeps me going. It was something unique to Norway, which doesn’t exist any longer.

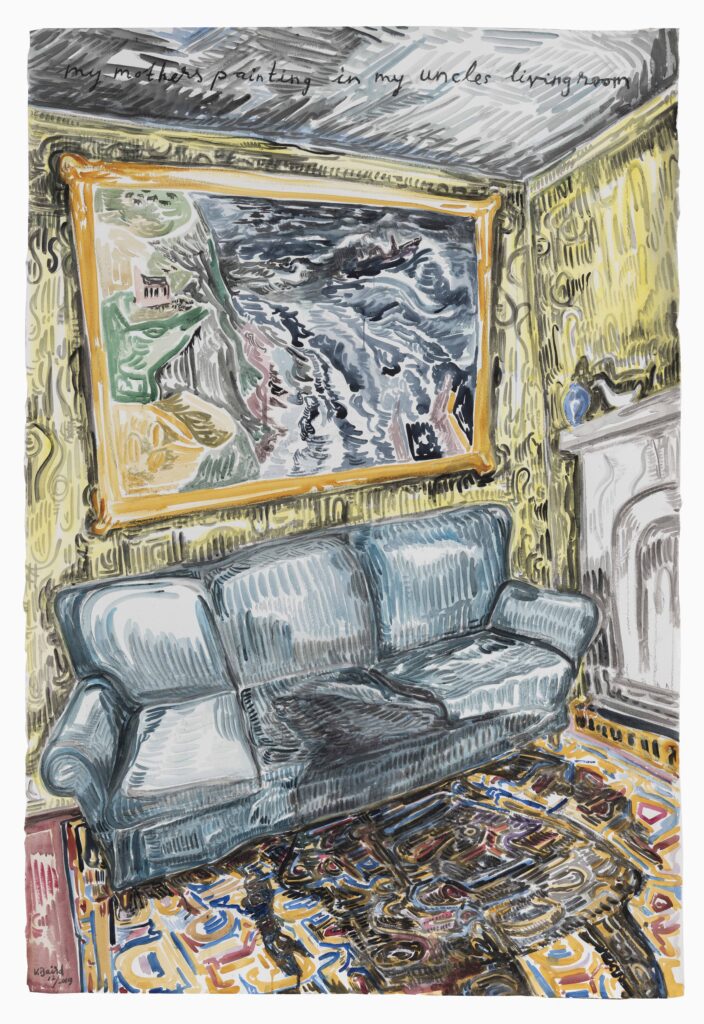

Vanessa Baird, Mother’s painting in uncle’s living room, 2019, watercolour on paper, 100 x 150 cm, courtesy the artist and OSL

Do you intend your drawings to be unsettling, or is that just how they end up?

They just end up like that. Really, they’re just notes from my life. I made a book, which came out in December, called There’s Nothing Like Staying At Home, comprising 200 new drawings. I didn’t realise how claustrophobic they were until they were all put together. I got a review, which said: “This is not a home I would like to stay in”. My life has been claustrophobic throughout. I’m used to being lonely, both due to illness and as an artist. But you keep yourself occupied. I put all my focus and energy into my drawing. I don’t have energy for anything else. There’s a lot of tension, nerves, anger and frustration. Doing them gives you time off from yourself.

Vanessa Baird: If ever there were an end to a story that had no beginning is at Drawing Room, London, until 9 May

Top photo: Portrait of Vanessa Baird, courtesy the artist and OSL contemporary, photo by Frode Fjerdingstad