In his mercurial and dreamlike paintings and drawings, Kristian Evju tells tales with jumbled narratives. His works – a blend of the contemporary and the gothic – draw on, and riff on, traditions of collage, drawing and painting in their exploration of the past and present. They merge geometry and figuration just as they blend subjects as diverse as computer grids, vintage photography and documents. They’re like surreal history lessons.

Kristian Evju was born in 1980 in Kongsberg in Viken county, Norway. He studied at Edinburgh College of Art and Chelsea College of Art in London where he is now based. Evju has won the Painter-Stainers Prize for Drawing (2016), held solo shows at Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh, and Galleri Semmingsen, Oslo, and published Fingerpflanzen, a collection of stories by Austrian author Anna Kim, based on – and illustrated with – his pictures.

As Evju emerges from lockdown in London, he talks to Norwegian Arts about storytelling, psychology and painting in solitude.

Can you tell us a little about your roots. What very first drew you to painting and drawing – what was your life like then?

I grew up in a fairly remote forest valley in the the south east of Norway, in a family of five. My father became a full-time artist around the time I was born, and my parents bought a small, secluded place where my dad built a large studio. He had just started collaborating with the Norwegian filmmaker Ivo Caprino [famed in Norway for his stop-motion animated films of the 1960s and 1970s] on a number of fairly large projects that would very much shape my childhood and the way I look at painting and drawing.

Caprino had already made a series of animated films based on the fairytales and legends collected in the mid to late 19th century by P. C. Asbjørnsen and J. Moe, and in the early 1980s he contracted my father to make backdrops and physical tableaus of the fairytales in a family amusement park called Hunderfossen in Lillehammer. So I grew up surrounded by a lot of people that were in some way or other involved with the arts, and my childhood was full of stories.

My parents decided against having a TV, so in the evenings I would often read or draw. I have two sisters – and we would often ask dad if he would illustrate our flights of fancy, which he readily did – anything from talking cars and scary but naive trolls, to flying castles or sleeping dragons. In many ways this is still what I do – painting and drawing is a way of exploring and narrating my reality – internal or external.

You grew up in Norway but your art education has been in the UK, how have the two nations informed your work?

I think much of my understanding and reading of contemporary art – how and why it’s made, and the context in which it’s seen – was developed in the UK. But the way I filter visual stimuli – the way I look at the world and collect imagery to paint or draw from – was of course constructed and conditioned in the remote forests of Norway. There’s a certain pallet, and perhaps a rhythm, to the way I compose my work – that I also recognise in the works made by contemporary colleagues in Norway.

My education was naturally quite Anglocentric, but years of traveling and seeing art in different contexts have broadened my horizon a bit, hopefully. I think 2003 – 2011 was a quite fortunate time to be a student in the UK, as it seemed as if the world of art was somehow centred in London. Maybe things will change a bit now, but I am still incredibly grateful to live in an epicentre for contemporary culture.

You initially studied Psychology at the University of Oslo, what can art bring to the field that science cannot?

As a contemporary art student, you are no longer taught how to paint or draw – my entire masters degree was centred around critical thinking, so maybe it’s not so different from other studies. I think there’s a healthy overlap and synergy, and I know that the psychology studies served as an incredibly important gateway into academic art for me.

In terms of what art can bring to the field of psychology, there are a lot of different answers I’m sure. You develop a very unique way of thinking and looking at the world as an artist, and whereas art can be seemingly chaotic and volatile, the art world itself can be surprisingly predictable, so maybe there is something to be found in the juxtaposition between artist and audience, or in the semiotics of art itself? Perhaps an escape from the written word?

Do you see painting and drawing as storytelling?

When I’m in the studio, I’m basically exploring. I have vague plans, but quite often I shoot first and ask questions later – a sort of John Wayne approach to painting and drawing. I work very slowly, and often with historical, photographic sources, so I can get quite intimately familiar with the visual aspects of what I’m painting – even if I have no additional knowledge of the subject.

I like the idea of myself as a storyteller – but maybe not in the traditional way. I see my work as more similar to film trailers perhaps – there’s no introduction, nor any resolution – you are just thrown straight into the midst of whatever narrative there is, and as such, I merely set the scene – and leave it up to the audience to provide meaning.

Your paintings and drawings play with historical sources. Are you interested in the notion of fake news?

In a way, you could say that I paint historical fiction – based entirely on factual visual research – so I am naturally very interested in why we interpret the world as we do.

There is a clear disillusionment towards facts, truth and authority since we entered this post-digital, post-truth period in history. We can no longer trust our own reading of reality, and this makes us question recorded history in new ways. Linguistically truth is a question of semantics and by creating fictions from facts perhaps I mirror the way we assemble our understanding and narration of the world around us.

How has the coronavirus crisis impacted your work and working practices?

The Covid-19 pandemic has been very exposing in many ways. As a full time artist my life hasn’t changed that much, but maybe it has re-instilled in me a sense of how fragile society and civilisation really is. I have had a lot of uninterrupted time to paint, which I have really enjoyed, but of course I miss having a physical social life. I miss seeing physical art, theatre, restaurants and live music, but I am surprised by how little I’m affected by not traveling. I travel too much, and often not with a good enough reason. So it’s a good wake-up call.

I have had to cancel and postpone most of the planned exhibitions this year, which can be a bit stressful, but on the bright side I have had more time to make works, and plan the upcoming shows. Overall I think my lifestyle has prepared me better than most for this situation, as I’m used to various levels of uncertainty and isolation.

For more information about Kristian Evju’s forthcoming exhibitions visit kristianevju.com

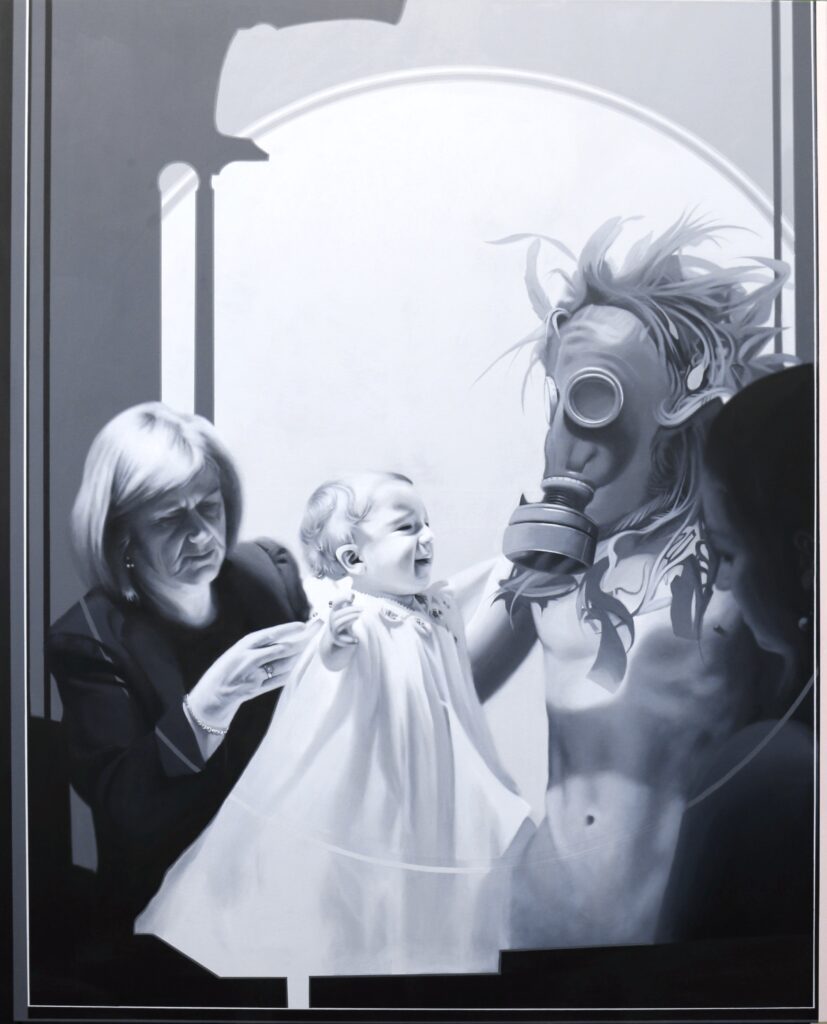

Top Photo: Kristian Evju painting Baptism of Faun in his studio during lockdown

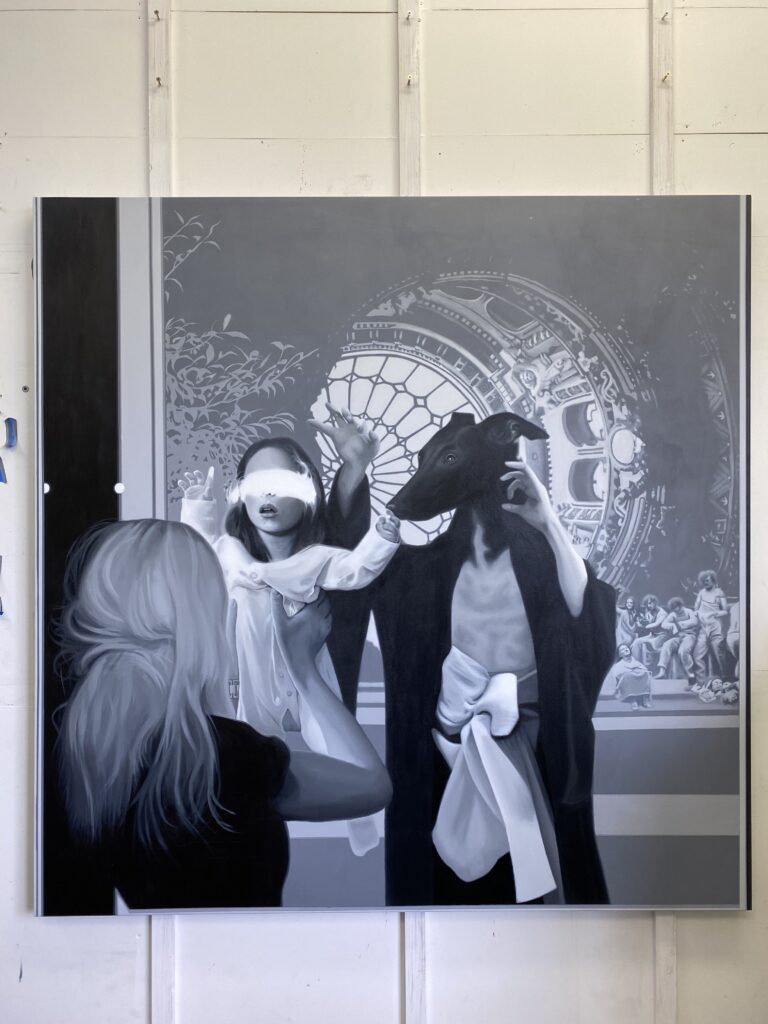

Update, August 2021: Kristian Evju has been announced as the Winner of the Figurative Art Prize 2021 for his painting Interventions IV. The painting was included in the exhibition Figurative Art Now, alongside nearly 400 other works, chosen by judges Jo Baring, Director of the Ingram Collection; Andrew Gifford, Artist; Clare O’Brien, CEO Federation of British Artists; Barbara Walker, Artist; and Jonathan Watkins, Director of the ICON Gallery.