The work of Norwegian film-maker and photographer Heidi Morstang explores the significance of landscape through the social, cultural, environmental and archaeological histories embedded within.

Morstang is Associate Professor in Photography at the University of Plymouth, and has exhibited her work internationally since 1995. Two of her works, Prosperous Mountain and Ringhorndalen, are included in the UK touring exhibition Seedscapes: Future-Proofing Nature. Postponed by the Coronavirus pandemic, the exhibition is due to open in September.

Here she shares with Norwegian Arts the story behind these two works, which while very different were both inspired by her fascination with the Arctic and especially Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago situated midway between the Norwegian mainland and the North Pole.

These two works are inspired in different ways by Svalbard. How would you describe this unique place?

I travelled to Svalbard to make the film Prosperous Mountainin February 2013, when the annual seed delivery to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault took place. Stepping out of the plane in Longyearbyen, the Arctic air and intense blue light created vivid sensations of this unique place with its constant weather changes, luminous light, barren mountains and fjords. Light changes rapidly from polar night towards midnight sun; it shapes the landscape in a way that cannot be experienced anywhere else.

As a Norwegian, Svalbard felt familiar due to its culture and language, although the archipelago also has a strong international community of researchers. Svalbard is remote from the mainland, although it has become more accessible recently, with more flights.

My deep connection to nature stems from growing up in Norway with its sharply defined seasons and weather changes. Filming the first scene was a twilight scene of a pyramid shaped mountain illuminated by full moon and passing snow mobiles. Standing in front of these mountains reminded me of Harald Sohlberg’s painting Winter Night in the Mountains. The landscape had similar luminous blue tones that are almost out of this world.

This is the High Arctic where climate change is seen, touched, heard and felt. I felt as if I was intruding in a very fragile place. I changed a roll of film in the camera, and a tiny piece of paper was caught in the wind. It was upsetting, as I could not catch it due to the strong winds; consequently, I had left a mark.

What are the challenges for a film-maker posed by the extreme nature of working in Svalbard?

During filming, the coldest day was -32 Celsius. The additional wind chill factor in gale force wind made it -52 Celsius. Many layers of clothing were necessary, so operating the equipment was challenging. Pushing small camera buttons or sound recording equipment is quite difficult with thick mittens and gloves. Changing film in the camera needs to be done without gloves; doing this outside was impossible. These sensory experiences cannot fully be translated into film or photographs although the works can create an allusion.

Encountering polar bears, inhabitants of Svalbard, is another risk. I did not see any, however I did see a beautiful polar fox running in the snow in the blue twilight. There are such extreme and rapid weather changes in the Arctic; we experienced sudden blizzards and white-outs that forced us to stop filming and seek shelter. The Arctic is a reminder of a shifting focus: from human-centred to nature-centred.

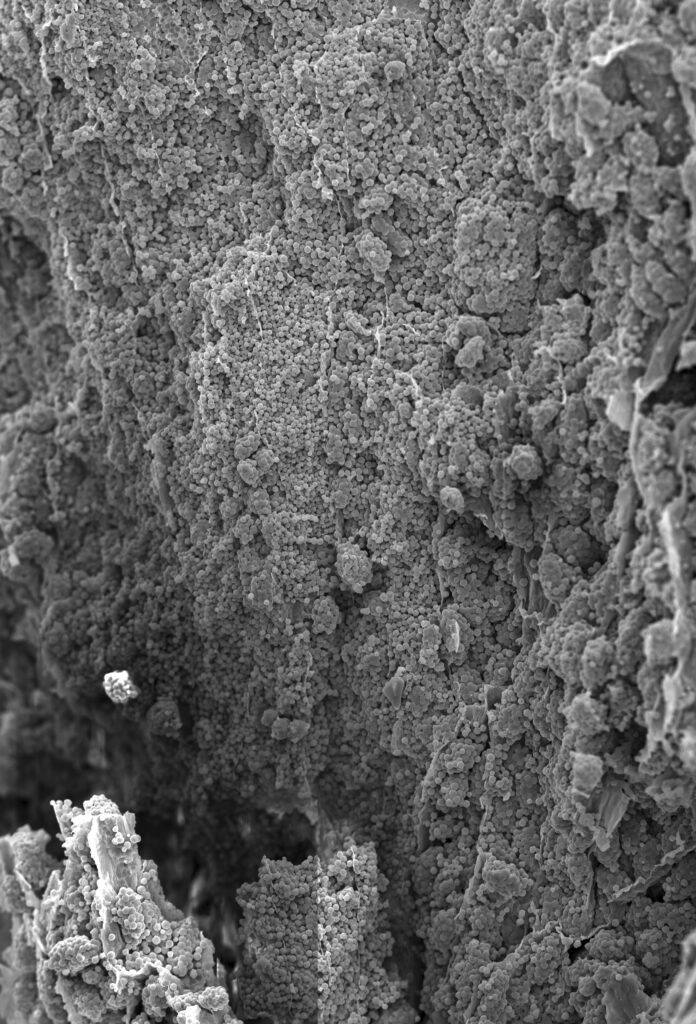

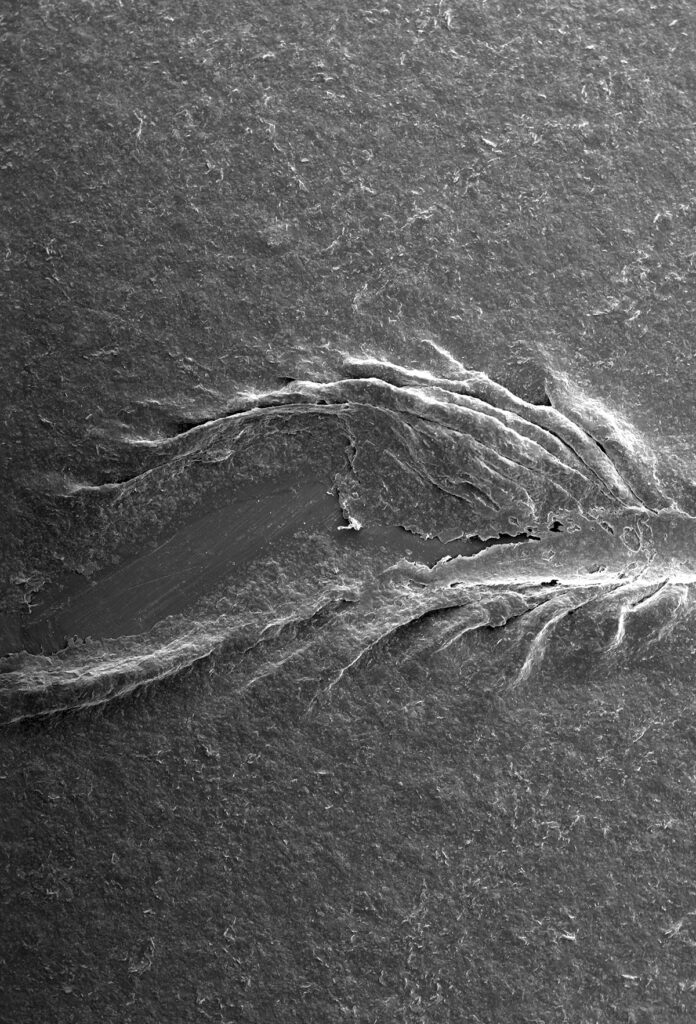

Your series Ringhorndalen uses electron micrography to reveal the intricate beauty of arctic flora at the smallest level. How did you come to use this technique?

After I made Prosperous Mountain, I wanted to work with seeds from Svalbard. I was intrigued that anything could grow in such a barren landscape. The discovery of Arctic flora was a surprise, as the summer is short and intense. Arctic plants are perhaps resilient to the extreme weather, although not to climate change. This thought became a fascination, alongside the news that Russian scientists found 32,000-year-old seeds in the permafrost in Siberia and that those native Arctic seeds later germinated.

The idea of working with the Electron Microscope emerged during another film I made in the Lofoten Islands in 2018. In the film, Pseudotachylyte, a team of geologists searched for signs of how earthquakes formed deep under the surface of Earth. The geologists worked with rock samples less than 1mm thick in the Electron Microscope. What was striking, was that formations seen were identical to patterns in satellite images and in geometric forms on the mountain plateau itself. One of the geologists said that “every earthquake starts in the size of a grain”. I wanted to see if we could discern a similar microcosm of landscape inside seeds.

Were you surprised by the results?

A terrestrial biologist from the University Centre in Svalbard sent me seeds from an expedition to a valley in Svalbard; a valley with a unique microclimate. I sliced the seeds into tiny fragments to prepare for the Electron Microscope. Other-worldly landscapes of unknown territories emerged: an imprint of the landscape of the valley. The thought that we can visually perceive other landscapes in a tiny seed is fascinating. How we can notice and connect microcosm to macrocosm is a thought that continues to inspire me, and the series Ringhorndalen may alert us to the poetry of place through images.

Do you think artists and scientists can gain from working together?

When artists and scientists work together our understanding of the world becomes richer. We have a similar curiosity. Scientific data can be difficult to comprehend without specialist knowledge, whilst artists can convey the same thinking in a different manner. Working together, or individuals working with several disciplines, is not new; Leonardo da Vinci is a good example of someone who sought an understanding of the world through art and science.

The purpose of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is open-ended. How do you imagine it will be used in future?

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is an example of hope for humanity. Hopefully, we will not need to use the facility. When filming Prosperous Mountain, it was the five-year anniversary for the opening of the vault. We were reminded of the very first delivery to the Seed Vault; it had been a collection of seeds from the seed bank in Aleppo when there was still peace in Syria. Despite the war, it is a poignant reminder that seeds from this region are safely stored in the vault; one day the seeds can be sown in peaceful territories.

The title of the film, Prosperous Mountain, became apparent when filming the scene of a blue truck dispersing coal. The mountain where the Seed Vault is situated used to be a coal mine. One kind of short-term prosperity had been extracted from the mountain, in the form of coal, and today another type of long-term prosperity is being placed inside the mountain as seeds, an attempt to safeguard food security for the global population.

As an artist whose work is informed by a concern for sustainability, do you feel positive changes might arise from the Covid-19 pandemic?

The pandemic has forced us to slow down. In the UK, there has been a common awareness of nature and spring. People have commented on hearing more birdsong, noticing more animals and insects. In news images, the sea has been clearer in Venice and there have been blue skies in Beijing. During lockdown, I have tended the bees we have at the university where I work. They have been thriving following their usual cycle of life. Noticing nature in our immediate environment during this time has perhaps been a very important lesson for many.

Can you tell us about what you’ve been working on most recently?

During the last year and in lockdown, I have worked on a new film in collaboration with world-leading climate change biologist Professor Camille Parmesan and evolutionary biologist Professor Michael Singer. Last summer, we filmed in Sierra Nevada, California, where they have studied one particular species of butterfly since 1978. The film portrays a beautiful and fragile time of two people who have dedicated their lifetime to one specific study: why butterflies migrate north due to climate change. They seek an understanding how a microcosm has an effect on our shared macrocosm. That all is interconnected.

This is what I seek to explore through the films and photographic work: from global seed collections in the Arctic, to geologists seeking an understanding of deep time through interventions in landscape, and how climate change can be revealed through the fragile existence of butterflies. How our imprints can alert us to the poetry of place.

For more information visit: hcmorstang.co.uk and Seedscapes: Future-Proofing Nature

Top photo: The Global Seed Vault on Svalbard featured in Prosperous Mountain by Heidi Morstang (2013)