The 2018 winner of the Queen Sonja Print Award, Emma Nishimura, is an artist looking to the past. This November, the world’s leading award for graphic art was presented to the Japanese-Canadian artist by HM Queen Sonja of Norway for a body of work that has delved into the experiences of her grandparents, two of the 22,000 Japanese-Canadians interned in Canada during the Second World War.

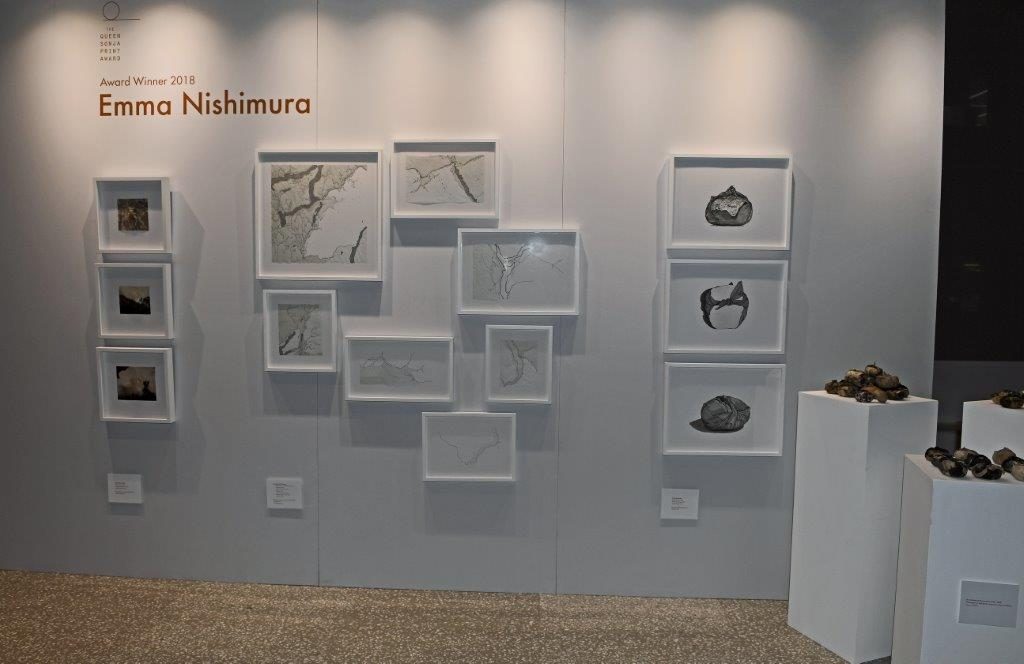

Nishimura, who is based in Toronto, bridges the boundaries between mediums. Her works incorporate – and combine – traditional prints, sculptural objects, installations, audio pieces, photogravures, drawings and writing. Following the award ceremony at the Royal Academy in London, we sat down with Nishimura to discuss how memory etches itself into our lives in different ways.

How did your work become so rooted in your own family history?

I got a grant from the Ontario government for a project in which I investigated my heritage and being mixed race. So I went to my mum’s basement, rummaged around, looking for old photos and I came across this box that said “Baachan’s Sewing Patterns”. [Baachan meaning grandmother in Japanese] This was about four years after my grandmother had died. I open it up and inside there was about 200 miniature paper garments of beautiful craftsmanship. To match all of those clothing patterns were five books of drawings – she had taken a drafting course in 1941 in Vancouver. Inside one of those books was a sheaf of notebook pages dated 1943. It was just Japanese names and measurements. In 1943, she was interned in the camps, she was making clothes in the camps. So, I found this box and I thought how do I talk about her work and her journey? How do I make my own work about all of these stories? I felt a responsibility to share them and talk about it.

Why choose printmaking?

I’ve always loved working with my hands. As a child I started pottery lessons at about five. And I sewed a lot. I’ve always been very physical with work and manipulated things. I discovered printmaking in high school and then really focused on it in university. I’m a planner, I like imaging what that big picture at the end is going to look like.

You have incorporated various types of papers – from photographs and written testimonies to maps – in your works. What potency do you think documents have?

It’s how do you make sense of them and what you do with them. I have these amazing photos but then they stay in this album. And there’s something incredibly special about sharing them. I’ve found my way to meeting people who my grandparents knew. But then everything stays tucked away in these boxes, or on the shelf or relegated to a basement. That has been a push in my work, how do I make these accessible.

Your work looks at the telling and retelling of stories. What interests you about that ongoing process?

Initially when I was doing the research I was talking to my mum and talking to my aunt, realizing that they have very different versions of the same story. All of these gaps. And I went back and reread this novel that I read as a kid and all of a sudden I discovered that what I had concocted as my grandmother’s experience was really that of the main character in the novel. There is this beautiful way that memory conflates. We don’t really know what the real version is.

Do you think there are parallels between the act of printmaking and that of revising and adapting tales?

Absolutely. Everything is endlessly reworked. I can make a finished piece but then I cut it up and reassemble it. Print affords you a bit of a structure but then there are so many steps along the way for different paths to appear.

You have turned prints into three-dimensional sculptural works using photographs and texts relating to the period of the internment. Was that always the plan?

No, I had no idea. I took sculpture early on and thought I don’t know if this is really for me. And now it’s a lot of how I think. With the sculptural pieces, the next step is to really grow that installation. I’ve made 350 and the goal is to make 1,000, for viewers to be really immersed in those stories and those memories.

What does winning the QSPA mean for you?

On a personal note it’s been deeply touching, I keep having to pinch myself. I found out on my birthday and I don’t think I’ll get a better present. Her Majesty has been just so incredible. And then on a professional level it’s an amazing launch-pad: there’s not another award at this scale or international recognition for printmakers. There are lots of painting awards but to have printmaking recognized at this level is a remarkable thing.