‘I do not talk about books. I talk about myself. And that’s to be trapped in something, because it never ends.’

In 2009, Karl Ove Knausgård already had two well-regarded, award-netting literary novels under his belt. When writer’s block hit him, he could easily have chosen to rest quietly on those laurels. Instead, he sat down and wrote a six-volume series of autobiographical novels that earned him international fame, critical notoriety and familial opprobrium in equal measure. Now, the fourth book in the series, ‘Dancer in the Dark’ has just been published in English.

Titling his 3,600-page bildungsroman Min Kamp (‘My Struggle’) was always going to raise eyebrows, and his negative comments about Nordic egalitarianism have ruffled feathers in Norway and Sweden, but it was Knausgård’s astonishing lack of restraint when exposing the most intimate secrets of his personal life and those of his family that have caused the biggest uproar – especially his unflinching and highly disputed treatment of his alcoholic father’s death. His father’s side of the family has stopped speaking to him entirely as result, and his ex-wife was given a whole programme to attack his account of their marriage on national radio.

Knausgård, however, has never made any claims about the objective truth of his ‘memoirs’, telling The Guardian: “There’s a lot of false memory in the book but it’s there because it’s the way it is, it’s real.” That is perhaps what makes the books such literary landmarks – not that they depict life as it is lived, but that they plug the reader directly into life as it is felt. When setting out on the project, Knausgård is quoted as saying, he decided that “everything I wrote must be true in the most banal sense of the word.” The average human consciousness, after all, is an ocean of banality – to represent it as accurately and forcefully as Knausgård intends, you can’t just build a narrative out of the seminal events, universal insights, and loftier musings; you have to include the boring bits – the bathwater stays in with the baby.

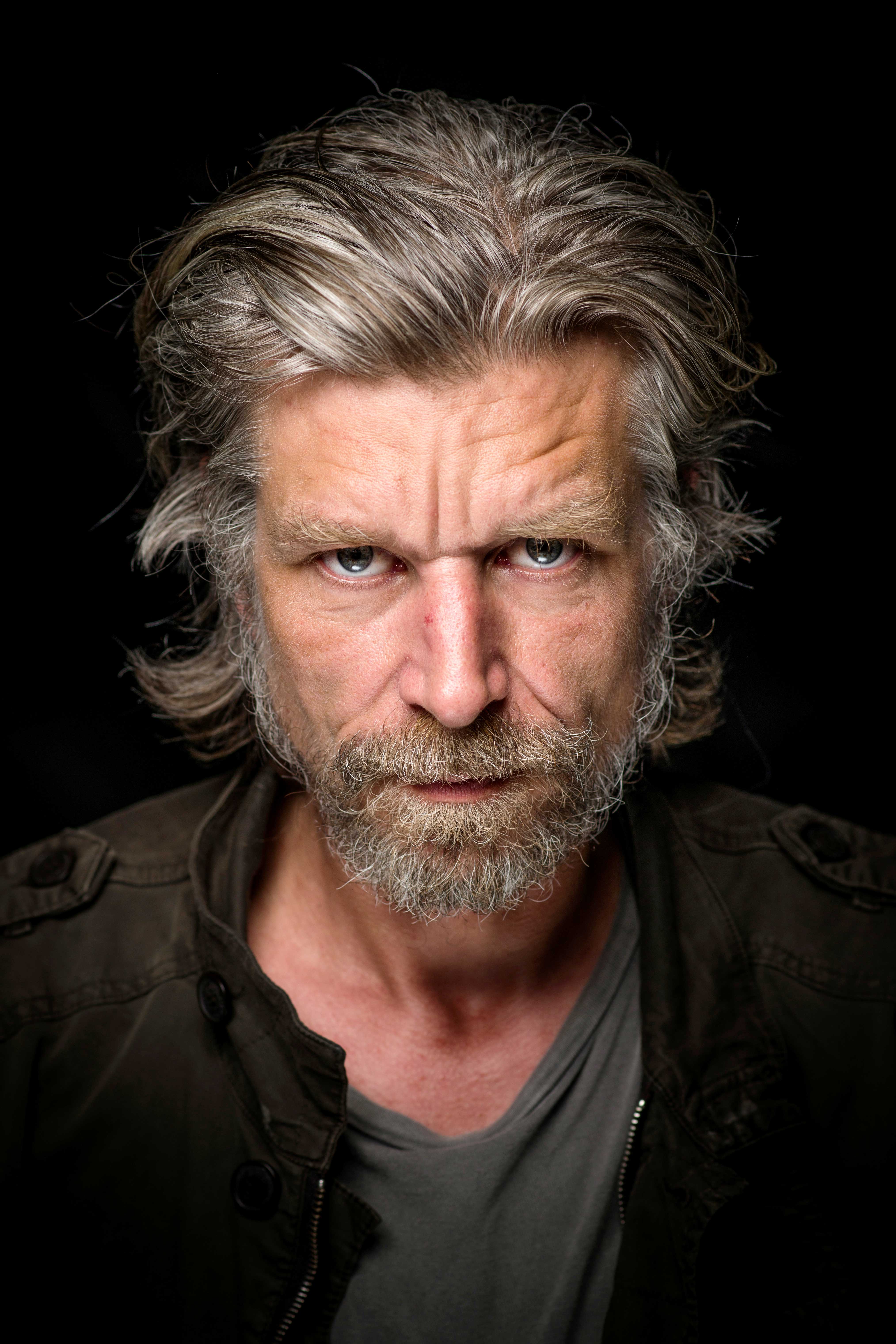

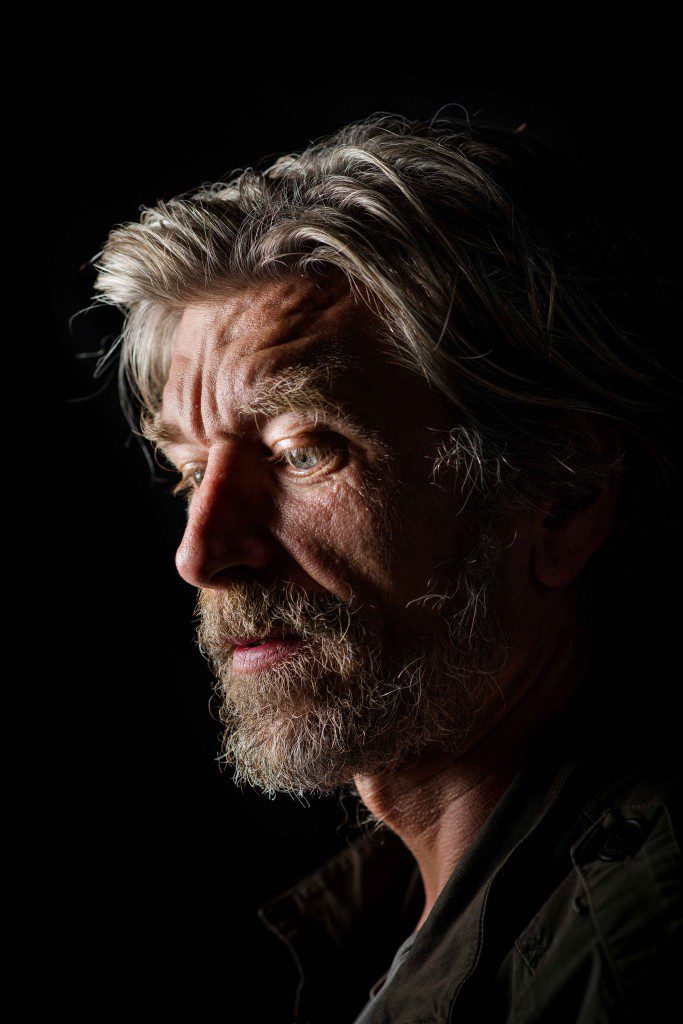

Photo: André Løyning

There are, of course, those who’ve found Min Kamp, with its leaping timelines, Proustian tangents and forensic treatment of the everyday, infuriatingly dull, but for many more, this ‘experiment in realistic prose’ has proved entirely mesmerising. Norway has bought half a million copies – for a nation of five million, that’s unprecedented – and it has been translated into 22 languages. Author Zadie Smith finds his books so compelling that she claims she “needs the next volume like crack” – now, with the release of Dancing in the Dark, she’s got her fix.

The fourth volume chronicles Knausgård’s time spent living in northern Norway at the age of 18, working as a substitute teacher, and covers the author’s sexual, romantic and existential misadventures in hypnotically humiliating – and often comic – detail. By telling this chapter of his own story, Knausgård sets out to capture the arrogance, ambition and insecurity of the teenage years. Whether he succeeds is a matter of opinion, but one thing’s for sure: no one has ever written anything quite like this before. As one reviewer put it “In exposing himself as a bundle of contradictions, Knausgård also allows us to see ourselves.”