On 17 May this year, as Norwegians in Britain celebrate Constitution Day, a special initiative will play out across the length and breadth of Scotland and Wales that speaks of a unique bond forged between Britain and Norway during the Second World War and which still endures today, as Christian House discovers.

Many Norwegians who fled the Occupation of Norway to join the Allied struggle against the Nazis never saw home again. And many were buried in British cemeteries, having died in conflict, through illness or in accidents while in exile. This 17 May the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in Scotland will remember the 58 Norwegians whose war graves it cares for, across 16 sites from Edinburgh to Shetland, just as the Norwegian Government cares for the British war graves in Norway. Commission staff, volunteers, and members of the public will visit each Norwegian grave, to place a tribute and commemorate these men.

The grave of Ivar Jacobsen, a sailor in the Norwegian Merchant Navy, in Lyness Royal Navy Cemetery on Hoy, Orkney. Jacobsen served on the D/S Mira and was wounded when she was sunk by a destroyer off Brettesnes on 4 March 1941. He was brought ashore in Aberdeen but died in hospital. (Photo: CWGC).

In Edinburgh, there will be a ceremony by the grave of Private Olaf Vennesland at Colinton Parish Church, next to the Water of Leith, attended by the Norwegian Consul and the Lord Provost, among other dignitaries. And in Cardiff, to commemorate the 11 Norwegians buried in Wales, there will be a short service at Dan-y-Graig Cemetery in Swansea at the grave of Sigurd Wathne, a Merchant Navy engineer who played for Norway’s football team in the 1920 Olympics and perished when his ship was sunk in the Bristol Channel in 1942.

Wreaths have already been laid at some of the more isolated sites. “One of our intrepid friends and colleagues has been over to Hoy in the coldest weather he has ever known in May,” says Patricia Keppie, the commission’s public engagement officer in Scotland. And in Olrig New Cemetery in the far north of Scotland, she explains, a group of air cadets is set to lay a wreath at the grave of Lieutenant John Schou of the Royal Norwegian Air Force. There are also Norwegian war graves in England and in Gibraltar, as well as many other countries around the world. Those in Scotland, however, are not “traditional casualties” notes Keppie. While some died as the result of enemy action, others died due to sickness or everyday misfortune, such as falls, often overlooked losses.

King Haakon VII is received at the station in Dumfries by the commander-in-chief of the Scottish command (Photo: Norwegian National Archives)

Keppie – who describes her job as a combination of historian, detective, teacher and custodian – devised this year’s initiative in response to a Norwegian act of kindness in 2020. A planned service at the grave of Flight Lieutenant Alexander Turnbull DFC, a Briton buried in Norway, was thrown into disarray by the pandemic. Turnbull, who was shot down while flying supplies to the Norwegian Resistance, was laid to rest in Lillehammer. Representatives from his former school in Edinburgh were prevented from travelling to the cemetery. When Haakon Vinje, Head of the Norwegian War Graves Service at the Norwegian Ministry of Culture, heard about the situation he arranged, through the parish council in Lillehammer, for a locally-made wreath to be laid on the school’s behalf.

Deputy Churchwarden, Ms. Reidun Bjørke, laying a wreath at the grave of Flight Lieutenant Alexander Turnbull DFC, who is buried at the Northern Cemetery in Lillehammer, on behalf of his old school, Stewart’s Melville College, Edinburgh. 17 May 2020 (Photo: CWGC)

An agreement now ensures that the CWGC looks after and maintains the Norwegian war graves abroad, and the Norwegian War Graves Service looks after and maintains the CWGC war graves in Norway. The majority of the Norwegians buried in the UK served in the Merchant Navy, although others served with the Royal Norwegian Navy and Army and were seconded to the RAF. Most left families. “There is one chap who had seven children,” says Patricia Keppie. “So, you just think of his poor wife left in Norway with these seven children. It’s shocking really.”

Norwegian forces in Dumfries parade past King Haakon VII and Crown Prince Olav V during the Second World War (Photo: Norwegian National Archives)

The ties between British coastal towns and Norwegian sailors are bound up by centuries of shipping routes and maritime tradition (a network of Norwegian Seamen’s Churches once stretched from Leith to Rotherhithe). In the war years, those foundations proved invaluable as relationships were built between the Scots and the Norwegians in difficult circumstances. After the war some connections were lost, others endured. In particular, they have remained strong between Dumfries and the Norwegian cities of Bergen and Haugesund, through informal soccer matches and reciprocal visits.

During the war, Dumfries provided a focal point for Norwegian arrivals, with a bustling reception camp and a women’s corps housed outside the town (they received camouflage training and worked in local hospitals). “We were only given a few hours’ notice before we were to receive the first Norwegians at the railway station,” recalled James Hutcheon, the town clerk.“Only those who had served during the First World War were prepared for the sight that met them: A group of men who had nothing more than what they stood and walked in.”

Members of the Norwegian women’s corps cycling through Dumfries on their way to work during the Second World War (Photo: Norwegian National Archives)

Many Norwegians were reminded of their own towns and countryside by the rugged Dumfries landscape. King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav visited the camp and training grounds on several occasions and a headquarters – Norges Hus – was soon set up in an old Dumfries restaurant along with a Scottish-Norwegian Society to host dances, workshops and lectures. Norwegian men gave speeches at Burns Night suppers, Norwegian and Scottish women formed a knitting circle.

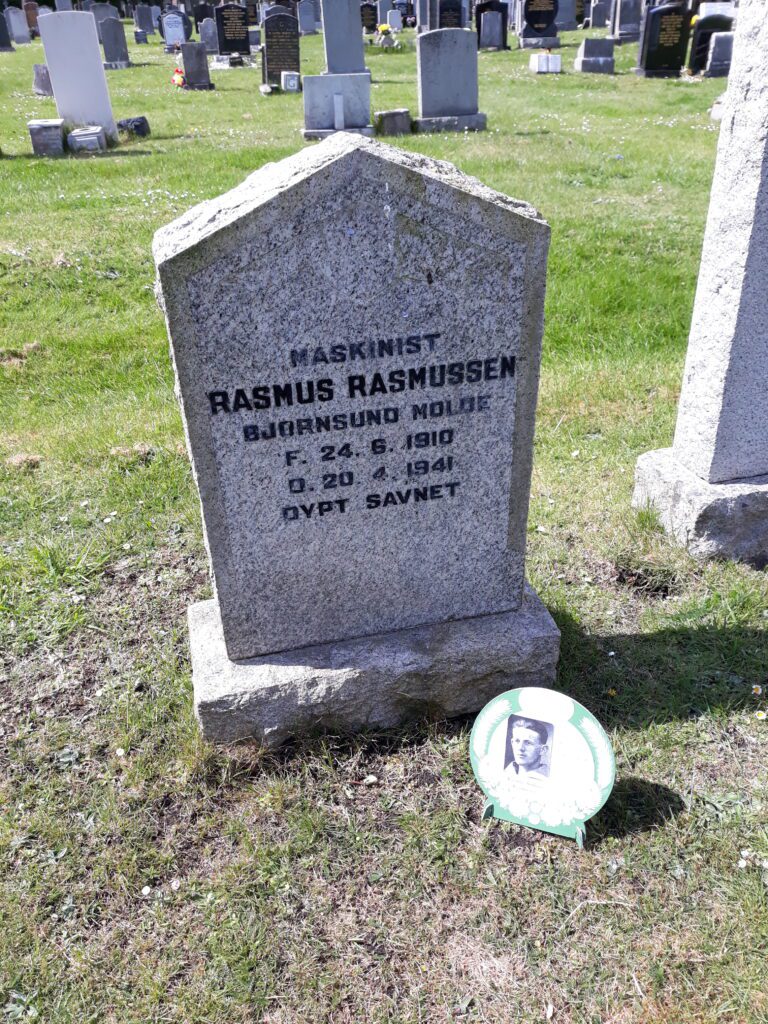

The grave of Petty Officer Rasmus Rasmussen, Royal Norwegian Navy, in Seafield Cemetery, Edinburgh. He served on the HNoMS Heimdal during the sea battles in the north of Norway and went over to England with the same ship. He died due to an accident at Leith. (Photo: CWGC).

The commemoration this year is a rare opportunity to remember this community of exiles who blended into – even married into – Scottish life. For those Norwegian men and women, the 17 May would have had additional importance, as Haakon Vinje explains: “Back home in occupied wartime Norway, the Germans had outlawed its celebration. It would surely have been considered a significant holiday, dearly held and celebrated; indeed, it still is by present-day Norwegians.”

A report produced by Vinje on those buried in Britain provides extraordinary details of uprooted lives, including the peace-time professions of these men. Most were not soldiers, or sailors or fighter pilots by profession; circumstances had changed the course of their lives. They were engineers, whalers, farmers and miners, there was even a Norwegian typographer serving in Scotland.

Norwegian forces in Dumfries being inspected by King Haakon VII during the Second World War (Photo: Norwegian National Archives)

“In the darkest hour of European history, the United Kingdom came to our rescue,” observed Wegger Chr. Strømmen, the Norwegian Ambassador to London, on the anniversary of the liberation of Norway this May. “The Norwegian royal family and government were graciously allowed into exile. This gave us the opportunity to fight on. Our sailors, airmen and soldiers fought side by side. We are forever grateful for the British contribution to the liberation of Norway. With the battles fought, a lasting friendship was forged.”

Today, that shared history is reflected in the act of remembrance. Part of Patricia Keppie’s job is educating school children about the casualties, of all nationalities. But are young people interested? “I’ve had groups of 13 and 14-year-old boys in cemeteries, and they say: ‘I’m bored. Go on, impress me’,” she says. “All I do is place them in front of the grave of Reginald Earnshaw, who enlisted in the Merchant Navy in 1941. He was 14, but lied about his age. Then I say: ‘What would you have done?’” The important thing, she explains, is to make the loss relevant to the listener. “That person in that cemetery years ago lived in your street,” she tells Scottish children. “He had your surname, he went to your school, your church, he played for your football team. And that really hooks them in.”

And, of course, similar conversations – important, surprising and moving conversations – are being had with Norwegian children on the other side of the North Sea.

For more information and images of the various events on 17 May, visit the CWGC website and their Facebook and Instagram pages.

For more information on the Dumfries / Norway connection visit: Ournorwegianstory.com

Top photo: Norwegian recruits in Dumfries in Scotland during the Second World War (Photo: Norwegian National Archives)