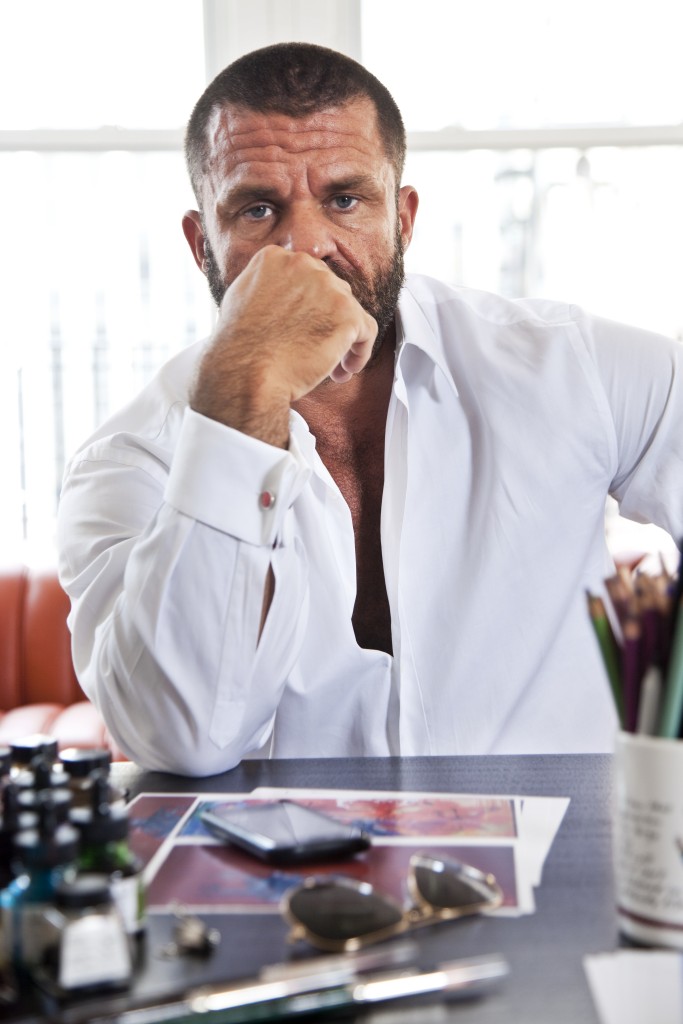

The controversial Norwegian artist Bjarne Melgaard is currently exhibiting at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in London. He talks to Norwegian Arts about his identity, his newfound mellowness and why he thinks painting is as important now as ever.

‘I don’t do art to make everybody like me and I don’t have any problems with people not liking my work.’ For an artist who has more often than not courted controversy with his paintings, films and installations, this is doubtless a good thing. A lesser character might have kowtowed to criticism and given up his art-making, but not Bjarne Melgaard. ‘I believe in freedom of speech. I don’t see my work as very mainstream, so when I get reactions saying it is stupid, everyone is entitled to their opinion. But I am also entitled to my opinion. As long as you know yourself what you’re doing, and you’re convinced about it, then you can handle anything.’

Melgaard’s current exhibition, which opened on 23 February at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, is by no means as controversial as many of his earlier offerings – which have seen him variously accused of racism, paraphilia and paedophilia. Showing alongside an exhibition of works by Sturtevant, Melgaard’s solo show – his first with the gallery in London – sees the 17th-century Ely Room filled with a suite of 14 new paintings, Bodyparty (Substance Paintings), each 180x180cm. Because of the age of the building, the heavy canvases could not be hung on the walls, and so they stand about, propped up on marble blocks. Melgaard, however, likes this ‘improvised’ feel, echoing the ‘casual easiness’ with which the works stand on the floor in his studio, and describes the whole coming together of the exhibition, proposed to him ‘at very short notice’ by Ropac’s new senior global director, and former director of Serpentine Galleries, Julia Peyton-Jones, as ‘very organic and very fast’.

“All my life I have tried so hard to gain entry to different people’s worlds and their notions of how things are supposed to be. I just don’t feel like I have that struggle anymore.”

Bilder av Bjarne Melgaard. 2010 -2012 © Johannes Wors¿e Berg

Alongside this real-world exhibition, Melgaard is simultaneously co-curating a virtual exhibition on Instagram, along with fashion editor Elise By Olsen, taking over the Ropac account (@thaddaeusropac) and showcasing the work of young Norwegian artists, designers and photographers. The idea is to capture something of what is happening in Oslo during the six weeks of the show. ‘Oslo is very behind in the art world,’ explains Melgaard. ‘Everything comes so late. It’s a bit like a time capsule.’

“This need to constantly document everything you do for people you don’t even know, to post selfies, and to check back for approval – I don’t understand this urge. It’s very empty and it’s not very intellectually challenging.”

Melgaard recently exhibited in London in the Saatchi Gallery’s ‘Painters’ Painters’ group show (30 November 2016 – 22 March 2017) and, indeed, this is an apt description of the artist. ‘Painting has its own quality,’ he explains.‘The hand is not relevant in society any more. Everything is done by machines. It’s as if you don’t need human beings. But painting still requires the human touch. It can only be done by hand. Even if you have a very hands-on approach with digital media, it can never have the directness of the action of a painting.’ Is it not, then, contradictory to be curating a virtual exhibition? ‘No, because in the same way that I like to work with the traditional quality of painting, I also like to challenge that medium. I’ve always been very contradictory in the way I work. I will make a work that says one thing and act in a way that says another. I think that it’s important to be in dialogue with your own time and to reflect upon it critically. The whole idea of a digital show is that it is critical of our embracing of the digital era.’

Collaborations are not new to Melgaard, having previously worked, amongst others, with jewellery designer Bjørg Nordli-Mathisen, internationally renowned architectural firm Snøhetta, and creative director Babak Radboy, with whom, in 2015, he launched a clothing line entitled The Casual Pleasure of Disappointment, coinciding with his first Ropac exhibition in the gallery’s Paris Marais space. The whole exhibition was put together in collaboration with fashion and furniture designers and hair and make-up artists, but Melgaard says that although he loves collaborating with others, he’s now ready to take a break from it and work alone for a while. ‘This show is much more raw, much more bare – it doesn’t have all the extravagance around it. Personally I like that approach more.’

“I don’t think it’s good for anybody to stay too long in one place. It felt like it was a good time to leave.”

Photo credit: Richard Kern

Having lived in New York for a decade, Melgaard moved back to Norway last summer. Primarily he returned to be close to his 87-year-old mother, but he had also tired of the pace of life in the Big Apple. ‘I don’t think it’s good for anybody to stay too long in a place. It felt like it was a good time to leave. I got tired of the people running around like hamsters in a cage.’ Was his decision influenced by Trump’s presidency as well? ‘It was a good reason to leave,’ he admits. ‘When the political climate became that toxic, it changed how I viewed America. When they select a fascist for President, you just wonder what’s going on.’

Life in Norway is quite different. Melgaard has a much closer dialogue with his immediate audience and people stop him in the street to ask questions. At the same time, he no longer has assistants helping him in his studio and his Bodyparty (Substance Paintings) capture something of the loneliness of being an artist, a theme also picked up by the Instagram project. ‘I think the substance of social media is a bit sad and lonely – this need to constantly document everything you do for people you don’t even know, to post selfies, and to check back for approval – I don’t understand this urge. It’s very empty and it’s not very intellectually challenging. And when you see who has the most followers, it’s really very depressing.’ Melgaard’s own account, incidentally, features a mixture of pictures of his paintings, his mother, his hairy chest, and his French bulldog Freya.

“Munch is a great painter. I love his work. But I’m more interested in the future. I’m not so into this retro-spirit where we have old heroes that we have to nag on about. I want to be my own artist.”

Melgaard was born in Sydney in 1967 to Norwegian parents. Although raised in Oslo, he maintains an affinity to Pacific culture and returned to Australia – as ‘a beach bum’ – for a period in his twenties. ‘I travelled all around the Pacific and it’s something I want to do again,’ he says, while also asserting his sense of Norwegian identity. ‘When I’m in Oslo now, I feel that I’m at home, in the sense that I have my family and my lover there. At the same time, I don’t feel at home anywhere. It’s a contradictory feeling.’

Norway has certainly adopted Melgaard as something of a national hero, and he is often spoken of in the same breath as Edward Munch. The paedophilia claims came about as the result of an exhibition, ‘Melgaard+Munch: The End of it Has Already Happened’, at Oslo’s Munch Museum in early 2015, particularly referring to the video Gym Queens Deserve to Die, featuring a man inserting a baby’s arm into his mouth in a sexualised manner. The show brought together the two artists’ work, but was never intended as a comparison. Instead it drew on common themes and motifs. ‘I think Munch’s a great painter,’ says Melgaard. ‘I love his work. But I’m more interested in the future. I’m not so into this retro-spirit where we have old heroes that we have to nag on about. I want to be my own artist. My work stands by itself. Of course it can be linked to Expressionist painting, there are references, but, at the same time, it’s its own thing.’

Photo credit: Gallery Thaddaeus Ropac

“No matter how you look at it, there’s still a long way to go for gay men and women to have the life that they maybe want to have. “

Melgaard doesn’t consider himself a political artist, but his work is rooted in an early identification with queer politics and queer identity from the 1970s and 80s. Another collaboration was with the American literary theorist Leo Bersani, author of Is the Rectum a Grave?, for ‘Baton Sinister’, part of the Norwegian pavilion at the 2011 Venice Biennale, where they filmed a fictional interview discussing some of the themes of the essay, including Bersani’s hypothesis of a homosexual longing for Death. ‘No matter how you look at it, there’s still a long way to go for gay men and women to have the life that they maybe want to have,’ says Melgaard. ‘They’re still very invisible in our society. You just have to challenge those heteronormative ideas.’

But Melgaard does not intend his work to be deliberately provocative. ‘I like to see how you can push boundaries,’ he admits, ‘but not for the sake of just pushing boundaries. There has to be a necessity for it.’ He chooses to work with themes, questions and imagery that he considers relevant and finds interesting. If that creates disturbance and people get provoked – ‘well, it’s not very difficult to provoke in the art world, is it?’ Since moving back to Oslo, Melgaard has mellowed a little. ‘All my life I have tried so hard to gain entry to different people’s worlds and different people’s notions of how things are supposed to be,’ he says, ‘and I didn’t succeed. Now I feel like I want to enter the gateway to my own world. I just don’t feel I have that struggle any more. I’m more interested in finding my own voice.’

Photo credit: David Oramas

About Bjarne Melgaard:

Melgaard was born in Sydney to Norwegian parents, raised in Oslo and studied art the Norwegian National Academy of Fine Arts, Rijksakademie in Amsterdam and the Jan van Eyck academie in Maastricht. Melgaard is seen as one of Norway’s most controversial artist through his provoking paitings, installations, photo- and video art.

Top photo: Johan Lindeberg