Anja Niemi is a very private exhibitionist. As a new retrospective book of her work – In Character (Thames & Hudson) – highlights, the Norwegian photographer is keen to play act and perform, but only within the safe confines of her frame.

Niemi lives in Norway but for many years only exhibited in Britain and America. Different selves, ocean’s apart. In this book there is nearly a decade of work on view, in which she features in many of her photographs, but always cloaked in the identity of others – showgirls and sisters, dancers and ranchers. Misdirection has rarely been so intriguing.

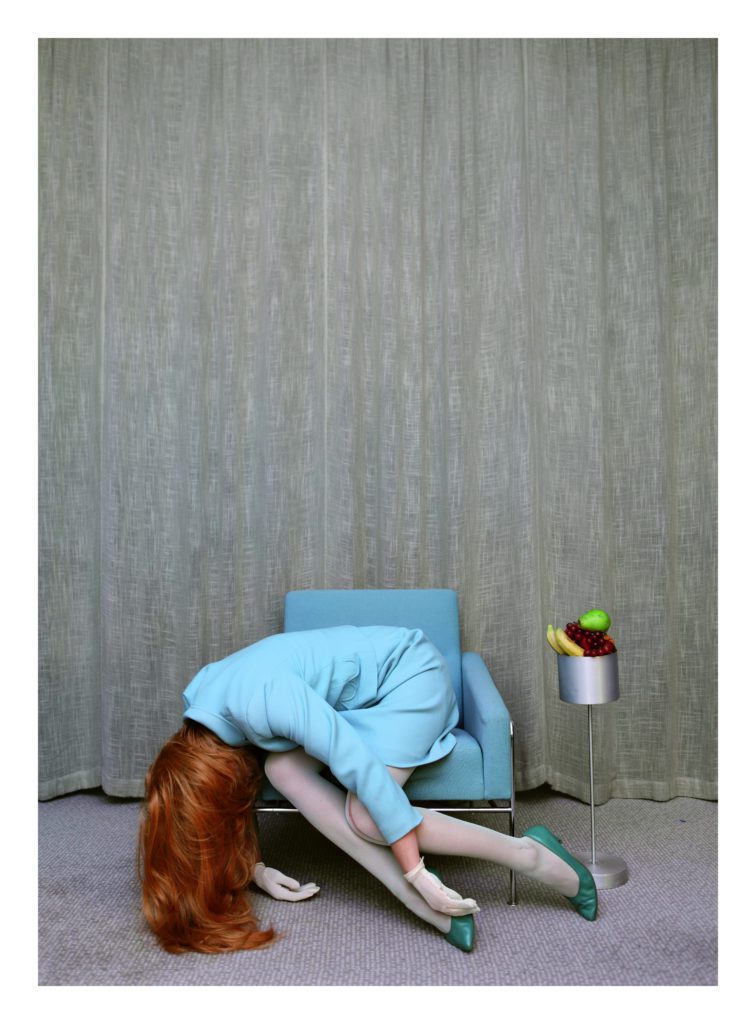

In her introduction to the book, Max Houghton, lecturer in documentary photography at London College of Communication, states: “Niemi is at heart a storyteller, a creator of fictions. She crafts exquisite tableaux in which she can hide in plain sight.” Her early works introduce this novelistic approach. In the 2011 series ‘Do Not Disturb’ Niemi delivers a gallery of images of herself made up as hotel residents, slumped or collapsed on the beds, sofas and floors of anonymous rooms. The palette is pastel, the tone mysterious.

Such gentle creepiness can be found in much of her work. In ‘Starlets’ she delivers a number of female film archetypes – The Receptionist, The Secretary, The Socialite, The Mistress – as if they have emerged from a bad dream rather than a good movie. These, and other imagined women, are like characters from a David Lynch nightmare. This series also saw Niemi begin to flirt with the theme of doubles and doppelgangers – casting duplicates of herself in the same photograph, often in conflict. In The Socialite, for instance, she appears twice, wearing identical party outfits, sitting in a sleek designer bath. One of her selves is unconscious. It’s like Blue Velvet set in a plush tub.

Niemi is the latest in a series of women artists who have embraced role playing. Frida Kahlo, Lorna Simpson, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman and Claude Cahun all projected fictional versions of themselves within their work. She even has Norwegian antecedents in two women photographers from the early 20th century, Marie Høeg and Bolette Berg, who set up a studio in Horten on the Oslo fjord. There in the 1900s they shot hundreds of glass negatives of themselves in various gender guises, from gentlemen sailors – sporting Victorian moustaches – to seal hunter.

Perhaps Niemi’s most obvious contemporary counterpart is the American photographer Alex Prager, whose technicolour images of California draw heavily on 1950s melodramas and crime thrillers. But whereas Prager looks towards Hitchcock, Niemi’s cinematic touchstone is fellow Scandinavian Ingmar Bergman, whose 1967 feature Persona – in which the personalities of a nurse and her patient slowly merge – was a key influence on her photographic adoption of other identities.

As Niemi’s career developed a broader array of influences emerged, from the literary to the theatrical. In ‘Darlene & Me’ (2014) she creates a photo-story about a pair of identical peroxide blondes holed up in a dusty desert retreat. It becomes clear that one is more dominant. Suspense builds, the situation escalates, a clash looms. It’s a novella formed from a flicker-book of photographs.

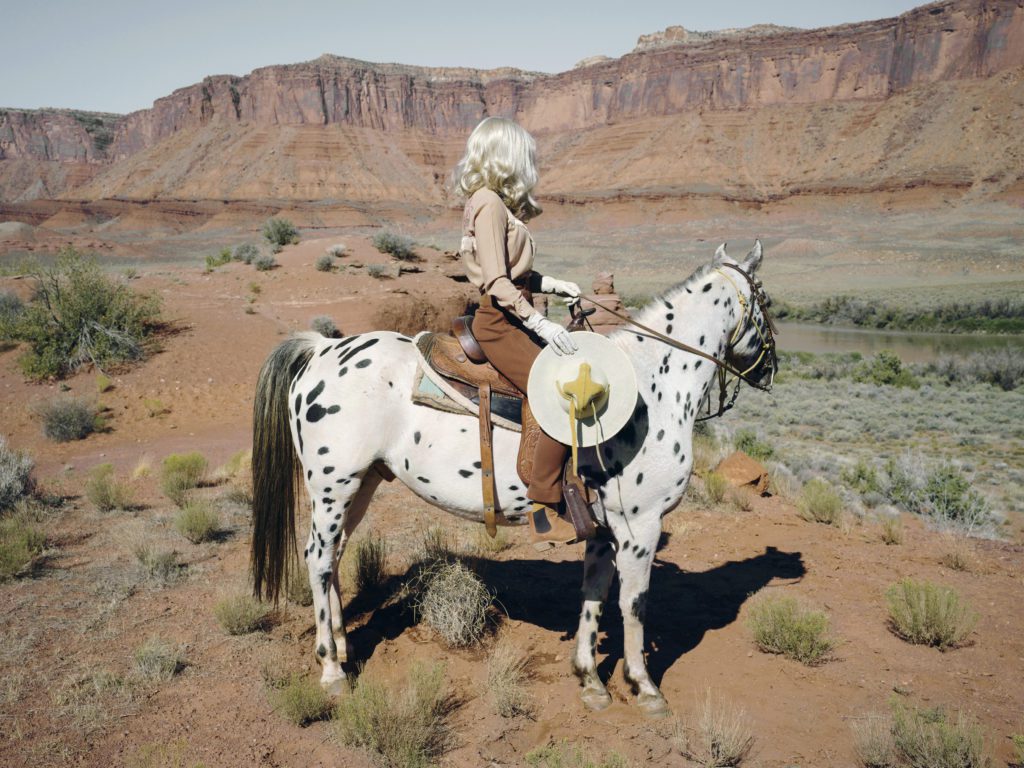

She composes her photographs with the skillsets of a costumier and a set director. “People’s things are an instant character trigger,” Niemi explains. “Once I can see my character, I start collecting her belongings – clothes, objects, accessories, wigs; anything she would have had that can help me form her.” A personality is signposted by their penchant for taxidermy, their dishevelled ice skates or their police fingerprint cards. She then installs these characters in oppressive situations: behind curtains and doors, overwhelmed by floral décor, framed within mirrors.

Niemi’s attention to detail can be seen to brilliant effect in ‘Short Stories’ (2016). Disillusioned with the ubiquity of digital photography, she spent a year producing a series of Polaroids – some quietly sinister, others ethereal – that play out like evidence from a road trip: still lives of bathing suits, dolls and axes, eerie interiors and landscapes of forests and frozen lakes. “I wanted to go back to where I started; to measure light, and peel back film – to recall the time when photography was precious,” she says. Niemi ended up with “140 tiny objects” – Polaroids of the ephemera of everyday life (possibly on the run) and the great outdoors.

In her ‘The Woman Who Never Existed’ series from the following year, Niemi imagines an actress whose sense of self evaporates when she steps off the stage. The photographs – showing Niemi as the actress dressed as a ballerina, toy soldier and geisha – investigate the psychological dangers of performance. Likewise, in her most recent series, ‘She Could Have Been a Cowboy’, she chronicles the Western alter-ego of a woman whose face you never see. But we do see her fantasies of ten-gallon hats, lassoes and Arizona dustbowls.

Throughout, the harshness of her subtexts – murder, voyeurism, loneliness, claustrophobia, transience – is belied by the softness of her colour schemes. She creates visual harmony in particularly un-harmonious circumstances. Her pictures feel like cotton wool embedded with grit.

Niemi has described how her struggles with dyslexia and social anxiety were initially a stumbling block for an aspiring storyteller. Photography was her way creating dramatic narratives without words. And, she notes, “I knew immediately that I had to control every element of the process myself in order to feel comfortable.”

The results are photographs that are intimate but remote. “I could have been proud to call myself a self-portraitist, if I were sure that is what I was,” she observes. “I have often puzzled over how I ended up doing what I do, but looking back to the beginning, it makes sense. I was using my body to tell stories in a setting that made me comfortable, alone.”

Anja Niemi: In Character is published by Thames & Hudson.

Top photo: The Chrysler © 2019 Anja Niemi.