There is a small library of books on Edvard Munch, including several already written by the art critic, curator, and expert on the artist, Øystein Ustvedt. But his new publication, Edvard Munch: An Inner Life, is intended to offer a wide-reaching, all-encompassing introduction for the lay reader.

Ustvedt couldn’t be better qualified for the task. He is head of the Stenersen Museum, a curator at the National Museum in Oslo and has curated several exhibitions of Munch’s work. Ahead of the book’s publication, Norwegian Arts talked with Ustvedt about what this volume will offer that others do not, his personal views on the artist he has spent so much time researching, and how he would like to expand his horizons in the future.

When did your interest in Edvard Munch begin, and what has kindled it over the years?

My first encounter with Munch was the docudrama Edvard Munch, by the English filmmaker Peter Watkins, which was shown on Norwegian television in 1974. The film was about art and an artist, but it was also, in itself, a piece of art. It was my first experience of art as a phenomenon. It made a huge impact, especially the almost abstract sequences.

You have written numerous publications on Munch already. What makes Edvard Munch: An Inner Life different?

The book is a comprehensive presentation, ‘Munch A-to-Z’ so to speak. While my previous writings have been devoted to particular subjects, this is a pervasive presentation, trying to get a grip on the Munch phenomenon as a whole.

What is the primary audience you hope to appeal to?

The book is intended for a wide and generally interested audience. It is not a publication for Munch scholars, nor is it a biography. It is a monographic introduction to Munch’s art and personality, and to Munch as a cultural phenomenon.

What makes Munch still so relevant to today’s audience?

Munch’s art seems to operate on several levels. People experience and appreciate different things. First of all, I think his art’s continuous relevance has to do with the fact that his imagery is easy to access and identify with. His works are about life lived by individual human beings, with an emphasis on emotions, attitudes and challenges. To me, Munch’s painting makes you aware of things: it helps you to deal with yourself and your relation to other people and to the world. It is about the value of nature, the relation to our immediate surroundings, to children and so on. But Munch’s art is also very much about medium-specific qualities, abstract painterly issues. His dealing with the materiality and possibilities of graphic techniques is deeply fascinating. He was such a good painter and graphic artist. I cannot think of any other artist who worked out such a wide range of different ways to put colours on a surface and thereby make it into something meaningful and substantial. He could make a painterly surface smell of bodily fluids. Running paint becomes open scars and running tears. You cannot divide form and content when it comes to Munch. What the paintings deal with is almost always deeply connected with how they are made.

What are some of the key events that you would pull out as pivotal to Munch’s personal and artistic development?

Although the book is not a biography, Munch’s life is, of course, very much part of the story. To me, you cannot really divide art and life when it comes to artists like Munch. First of all, you have his upbringing in a middle-class family, which struggled to keep up with its social standing. He was the son of a deeply religious, but not very successful, doctor. His childhood was marked by tragic losses. Later, he became involved with several bohemian milieus, first in his hometown of Kristiania (Oslo), then in Berlin and Paris. I also have to mention that he remained a bachelor, although he had several serious love affairs, and easily became deeply emotionally involved with women.

Munch wasn’t just a painter. What other aspects of his artistic career do you seek to bring out?

That’s a most welcome question as he was truly much more than a painter. First of all, he was also one of the 20th century’s greatest graphic artists. Almost self-taught, he gradually managed a wide range of techniques: woodcut, lithograph, etchings, dry point. His woodcuts are simply amazing. Then he was a prolific writer. He wrote a kind of manifesto, lots of poetic stories, and stream-of-consciousness-like lyricisms. At the turn of the century, he started to practise photography, experimenting with the medium. He even made some films and sculptures.

If you had to summarise Munch’s key themes in fewer than 10 words, what would you say?

To make art something deeply sincere, personal and emotional.

The book contains 130 colour illustrations – that’s more than one for every other page of the book. How do you go about selecting which to include?

Luckily, I was given a free hand in selecting images. The general idea was, on the one hand, to end up with a mix of iconic and well-known works, on the other hand, more marginalised and lesser-known ones. The challenge was also to include some of his “other” activities as an artist: photos, drawings, writings, sculpture.

If you could sit down with Munch for a drink, what one question would you be burning to ask him?

Hey Edvard, what do you think of this book? I will be free not to take your objections too seriously, but I will be all eyes and ears to what you think of it.

Which is your personal favourite work by Munch and why?

Munch’s art is as rich and many layered as life itself. However, my all-time favourite is his first version of The Sick Child (1886). I have analysed and worked on it on a number of occasions, but it is still very much a mystery to me. I cannot wait for this painting to be installed in the National Museum’s new building at Vestbanen, due to open next year. It is currently not on view. Not to have it available is like not being able to see a devoted friend.

Are there other artists, besides Munch, whom you’d like to bring to prominence some day?

In my role as curator of 20th-century art, I am currently dreaming and working on a presentation of Mark Rothko, who, by the way, was also an artist who dealt with making art personal, existential and emotional. To me, Norway has fostered two major and original 20th-century artists, Munch and the textile artist Hannah Ryggen. I have been so lucky to be able to work with both [artists’ work]. In the future, I hope to be able to give more attention to the almost unknown Norwegian artist Else Hagen, and the far more well-known German-born artist Rolf Nesch, who fled to Norway from the Nazi regime.

Munch is often paired with contemporary artists for exhibitions – Tracey Emin, for example, who cites him as a huge influence. If you could bring Munch’s work together with one other artist, dead or alive, for your dream exhibition, who would that be and why?

Emin might actually be my first choice! I thought of her as a contemporary, female Munch when I first saw her tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, and her tapestries. However, she would be seriously challenged by Louise Bourgeois. For me, Bourgeois is the queen of late 20th-century art and there seem to be lots of interesting connections between the two.

Edvard Munch: An Inner Life by Øystein Ustvedt is published by Thames & Hudson on 1 October 2020

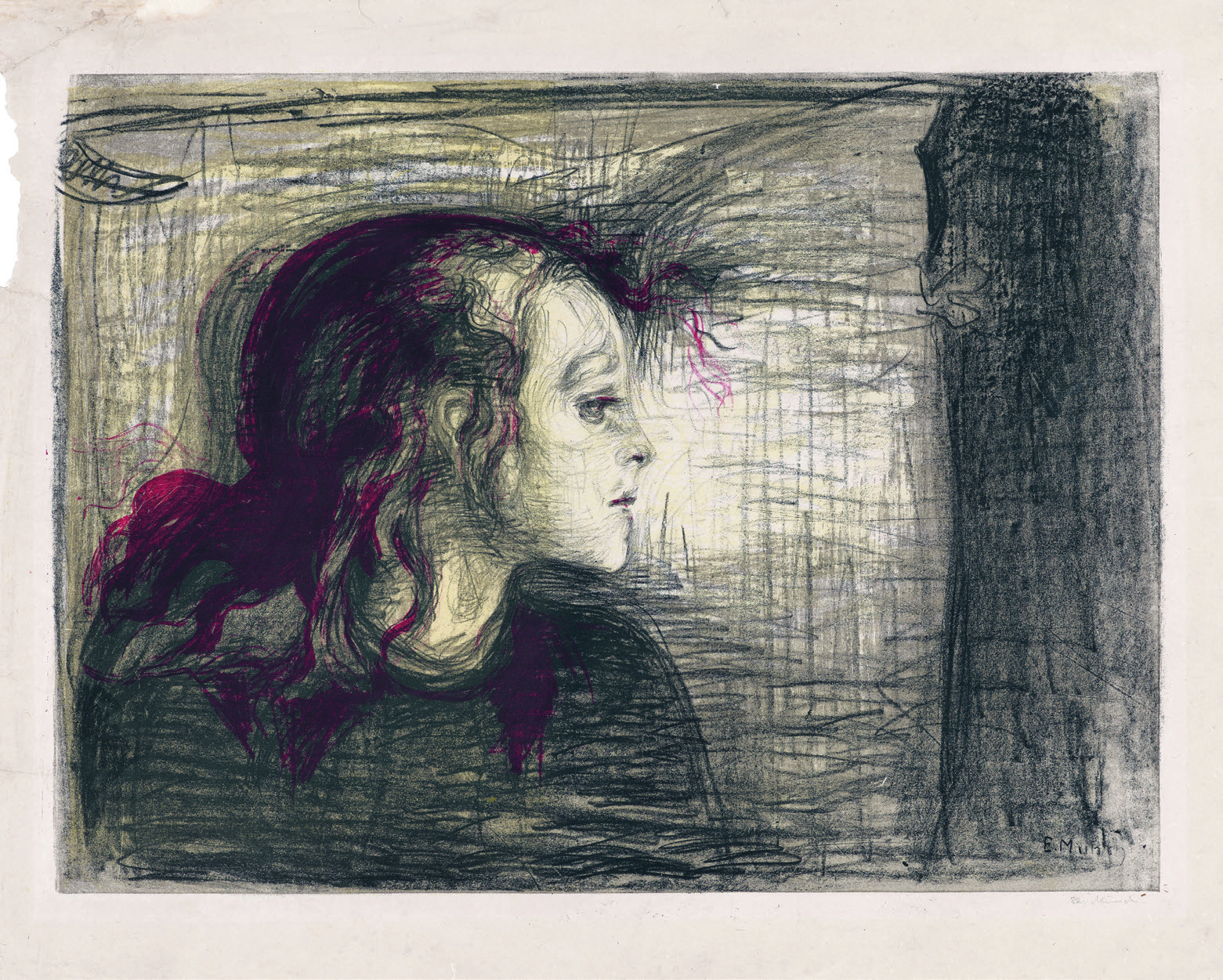

Top photo: Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1986, lithograph (Photo © Munch Museum)