Ever since 19th-century pioneers with large plate cameras began focusing on farmers in the fields and fishermen on the fjords, there has been a strong photographic tradition in Norway. But, as a new book about the contemporary scene reveals, the medium has moved beyond the pastoral. Christian House discovers how things have developed in the darkroom.

The explorer Anna Aurora Astrup peers through the prism of her old climbing goggles directly into the lens. Behind her, jagged snowy peaks pan out along the horizon. It is, perhaps, a quintessentially Norwegian image, a photograph that illustrates the long-held national passion for exploration. But not all is what it seems. For Anna Aurora Astrup is a fiction.

The photograph is part of a series titled ‘The Characters’, in which contemporary photographer Tonje Bøe Birkeland has depicted five women adventurers from the early 20th century. These women are fabricated, however, and all of the photographs feature the artist herself, in period costume and shot on mountain ranges, Arctic wastelands and ice floes. “I have, through ‘The Characters’, given women a position within landscape while exploring the authenticity of history,” Birkeland states. These are gender commentaries in the guise of self-portraits.

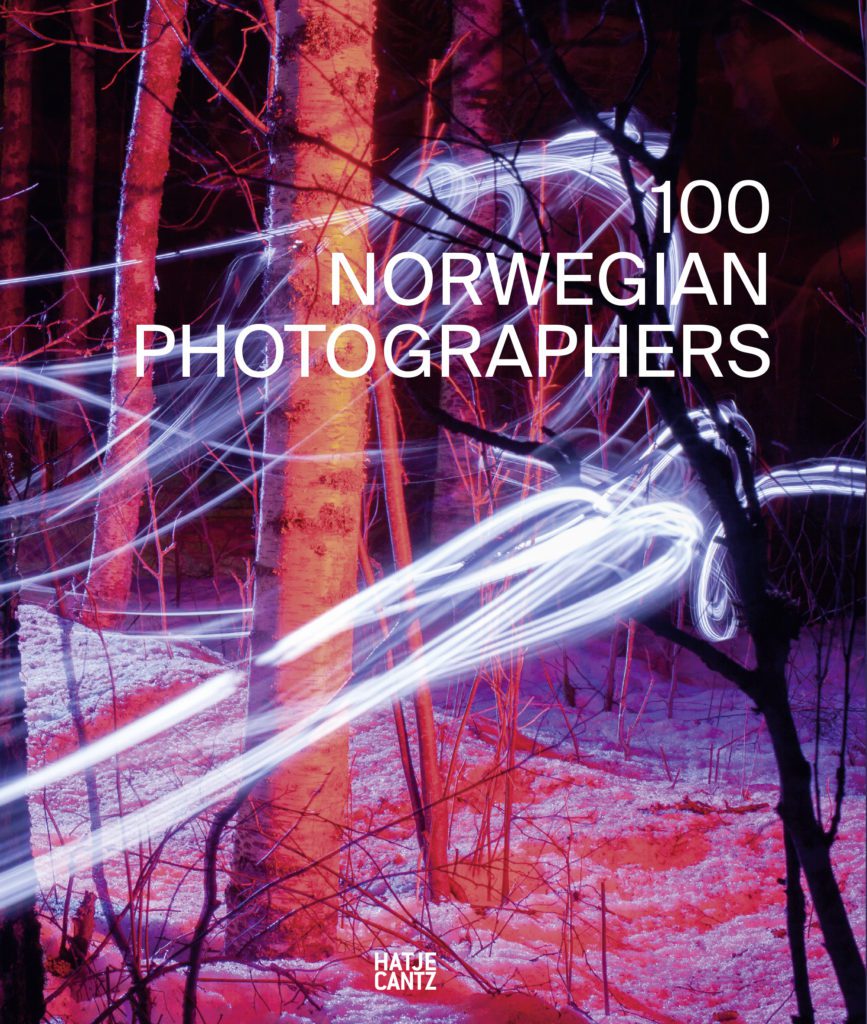

Birkeland’s work is one of the highlights of 100 Norwegian Photographers, a new book which looks at how photography has found a new place in Nordic culture. An anthology of work by living photographers, it is all-encompassing, touching on reportage, portraiture, abstraction, surrealism and, of course, some extraordinary vistas.

The project is the brainchild of visual artist Ina Otzko who, inspired by a similar project in Finland, curated the selection in the spring of 2018, naming one photographer a day on Twitter, before editing the book. “I knew it would be challenging in selecting one hundred,” Otzko says. Her choices, she adds, cover a variety of themes, including “human behaviour, identity, vulnerability and the climate.”

Linda Bournane Engelberth, Outside the Binary (Ynda Jas, London, 2018) (Photo: Linda Bournane Engelberth)

The photographers selected include major figures such as Robert Meyer, who photographed iconic 1960s artists such as Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol, but plenty of these photographers are relatively unknown, their work often surprising. Their ages range from 27 to 97.

The oldest, Johan Brun, was a press photographer for the newspaper Dagbladet for some 40 years and is celebrated for his sports photography and his coverage of The Beatles playing in Copenhagen. The youngest participant is Eivind Hansen, whose fashion photographs and portraits buzz with colour and sexual energy. The selection offers a chronology of passions caught by the shutter.

Jonas Bendiksen, Damaged Soyuz rocket with butterflies, Altai territory, Russia, 2000 (Photo: Jonas Bendiksen)

On the basis of this book, one can discern a new school of Norwegian colourists. Two thirds of the work illustrated is in colour and a striking aesthetic emerges, in which subdued backdrops are jolted – disturbed – by a boldly coloured subject. In Marie Sjøvold’s Midnight Milk, a woman in a turquoise dress leads a child along a rocky shoreline. The woman’s face is hidden behind a blood red balloon. Sjøvold’s photographs deal with family like a ghost story deals with the past.

In these pictures the physical world is mercurial. The country shots of Jens Hauge and Ivar Kvaal focus on the mysterious hangover of human interaction with the natural world. Elsewhere, as in the wildlife pictures of Pål Hermansen and the forest studies of Per Berntsen, the environment is a humbling, levelling presence. Architecture, meanwhile, materialises in mood pieces. And in Maate Aas’s unsettling works the geometry of buildings, nature and people all fuse together.

Much of the work featured in the book could be loosely described as portraiture. Among the elegant poses – Janne Rugland’s pictures of women on sand dunes could be film stills from an Ingmar Bergman feature – there are as many portraits that are unflinching, almost confrontational. For instance, Jo Bentdal’s pictures of serious-looking teenage girls look like Dutch Old Masters, they are images of youth steeped in melancholy. And Ingrid Eggen takes something akin to anti-portraits, frames in which bodies are manipulated into sculptural shapes, a kind of blend of photography and dance.

Antonio Cataldo, director of Fotogalleriet, the only gallery in Oslo devoted to camera-based art, maintains that 100 Norwegian Photographers highlights a sense of liberty – artistic, social and political. This, he says, is an extension of fri fotografi, a movement that began in the 1970s.

In fact, over the past century and a half, Norwegian photography has developed in several steps. “Portraits came first, then culture and landscape,” Otzko says. Rural photography, she explains, “was used in building up the branding of Norway within tourism.” The popular image of Norway, of a land of immense natural beauty, was in part formed by the dissemination of 19th and 20th century photographs.

But there have always been mavericks. The turn-of-the-century astrophysicist Carl Størmer adopted photography in his studies of society and the stars. Using a spy camera – peaking out of the buttonhole of his jacket – he took covert shots of ladies and gentlemen promenading along Karl Johans Gate in Oslo in the 1890s. “He also used photography to model, mathematically, the paths taken by charged particles in a magnetized sphere to explain phenomena such as the aurora borealis,” Cataldo notes.

The icons of Norwegian art were also fond of the medium. Edvard Munch’s interest in photography has been the subject of exhibitions at Tate Modern in London and the Pompidou Centre in Paris. And Munch’s contemporary, Harald Sohlberg, used his camera as an aide-mémoir on his travels, taking snaps that bear a striking similarity to the compositions of some of his best-known paintings (most notably Fisherman’s Cottage and Flower Meadow in the North). Sohlberg considered his photographs to be merely functional, but there can be little doubt as to their artistic merit.

Siri Ekker Svendsen, Between Attraction and Void (Ongoing series, started in 2015) (Photo: Siri Ekker Svendsen)

Like their antecedents, many of the talents featured in 100 Norwegian Photographers have found success far beyond Norway. Dag Alveng, who brings an almost spiritual air to his images of graveyards, asylums and racetracks, exhibits in galleries all across Europe and the Americas. And, from a younger generation, Jonas Bendiksen is now a member Magnum Photos. These photographers have also worked across the globe: there are photographs here that were taken in Britain, North Korea, Russia, Portugal and Antarctica.

This survey, while expansive, is really an introduction. There could be another 100 Norwegian photographers to pinpoint. But it ably illustrates how the country’s photographic talent continues to be – like Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s adventurers – guided by the imagination as much as the compass.

100 Norwegian Photographers is published by Hatje Cantz

For more information on the project visit: 100norwegianphotographers.no

Top Photo: Tonje Bøe Birkeland, Astrup’s Horn, Character IV Anna Aurora Astrup (1870-1968) (Photo: Tonje Bøe Birkeland)